7. FOR AN EPISTEMOLOGY AND ETHICS OF THE SINGLE CASE

Raffaella Campaner, Silvia Zullo

This contribution aims to provide some insight on rare diseases, addressed from the point of view of epistemology and bioethics. These are two distinct views, but in clear relationship with each other, which we believe can bring out relevant aspects inherent in our ways of dealing with rare diseases, both in biomedical research and in the clinic.

7.1. Models and single cases

The EURORDIS-Rare Diseases Europe portal, an international non-governmental organization representing patients suffering from 894 rare diseases, states that rare diseases, also known as an orphan disease, are diseases that affect a small percentage of the population. “The European Union considers, a disease as rare when it affects less than 1 in 2,000 citizens […] Rare diseases are characterised by a wide diversity of symptoms and signs that vary not only from disease to disease but also from patient to patient suffering from the same disease”. In what respects does this “variety” constitute something peculiar and impact on the elaboration and use of medical knowledge?

Indeed, science aims to identify regular patterns in phenomena, and to design models representing them effectively. Models are elaborated through abstraction and idealization procedures, providing frameworks in which the pathology is represented in its ideal features. The doctor’s task will be to establish the correct relationships between the general model and the individual patient, who never presents all and only the elements figuring in the model. The ability to correctly grasp these relationships is important in the definition of a disciplinary area: “Grasping the peculiar features of a discipline amounts to, among other things, shedding light on the distinctive relationship, by nature or degree, it draws between these two aspects: single facts and general models” (Gabbani 2013, p. 15).

Various views address this issue, directly questioning the relationship between biomedical research and clinical practice, along various axes. From a purely theoretical and principle point of view, are there reasons to privilege portions of knowledge that can be generalized or, at least, widely applicable, over information referring only to the individual case – and therefore, in a medical context, to prefer knowledge on “typical” conditions to research on rare ones? In an epistemological perspective, the role of forms of general knowledge is debated. Empirical knowledge starts from the observation of individual cases and “there may well be a regularity corresponding to each singular fact, but the regularity does not constitute the truth of the singular claim, nor is it necessary for its confirmation. […] Regularities have no privileged position. Singular claims can be established just as reliably” (Cartwright 2000, pp. 47-48). Furthermore, that phenomena are governed by regularity is an assumption, and can be disputed. Indeed, the world could prove to be dominated by variations, rather than repetitions, by disorder rather than order (Dupré 1993; Cartwright 1999). The belief that forms of general knowledge, capable of progressively unifying an increasing number of cases, necessarily provide a better understanding of the world, and are therefore preferable, cannot be taken for granted.

In a framework that questions the relationship between general models and single cases, what role is attributed to rare diseases? Are these problematic cases to be marginalized – for epistemological and/or pragmatic reasons – or can they count as epistemological resources? On the one hand, diseases occurring with particularly low frequency tend to be conceived as puzzling; on the other hand, at least two aspects foster further reflections. A phenomenon which happens to be widely discussed in the international literature is so-called disease mongering, i.e. the “promotion” to the status of “disease” of a condition that is widespread in a given population, thus making it the object of treatment (see, for example, Wolinsky 2005, p. 612). Paradoxically, we are thus in a situation where research is struggling to find new and specific treatments for a few patients, actually affected by rare diseases, and, at the same time, diseases are “invented” through the re-categorization of routine conditions as pathological conditions. The broader underlying issue is the definition of “normality”, from which the pathological emerges by difference: what notion of normality – natural/functional, statistical, conventional – do we assume? Who is entitled to set its thresholds?

Another interesting element is given by the extensive medical literature on case studies, focused on problems emerging “in situations where diagnosis would be difficult or particularly tricky, and describe uncommon or even ‘unique’ clinical occurrences. […] Single cases […] capture exceptions or highly unusual manifestations of health and disease” (Ankeny 2017, pp. 310-311), where there is often “an element of surprise” (Jenicek 2001, p. 83). The space dedicated to case studies – including the creation, for example, of the Journal of Medical Case Reports in 2007 – testifies to the recognition of their epistemic role: case studies are individual cases not simply in a numerical sense, but insofar as they introduce some novelty on a descriptive/explanatory/therapeutic level, and it is for this reason that they are regarded as worth considering. The epistemic process characterizing the dynamics of the construction of knowledge between the general level and the single case will then be iterative. The description of an actual single case is to be related to the extensive knowledge which has already been acquired, progressively abstracting from some characteristics to highlight similarities with what is already known. In turn, general knowledge can be confirmed or, vice versa, corrected and perfected, in light of the peculiarities of the individual case (see Ankeny 2006). Single cases stimulate new cognitive processes, encourage new discoveries, bring to the fore anomalies and limits of the accepted theories, and impel to create new approaches. Rare cases can thus play an important role not in a statistical sense, in the development of some average or standard framework, but as a comparison and control for the models accepted by the scientific community at a given time. The individual suffering from a rare disease is relevant not because her condition exemplifies at least some regularities, typical of the human body and its functioning (which it certainly does), but because of her distinctive, non-typical features. At the same time, it should not be excluded a priori that even the peculiar characteristics may have, in the end, a supra-individual scope and provide cognitive contents which can prove to be relevant also on a large scale.

Concluding our epistemological reflections, let us raise the following question: in what respects can (and, at least in part, must) medicine be a science of the individual? Certainly not by virtue of any alleged disciplinary inexperience, but due to the high variability of its objects of investigation, i.e. diseased subjects. If a medicine “of the individual”, including also individuals with a rare pathology, may encounter difficulties, it is important to acknowledge the full range of its possible impacts on the methodology of scientific research, the contents of the clinicians’ training, and, as we will see in the following section ethical dilemmas. If awareness of the uniqueness, actually, of every patient is growing – thanks to, for example, to the progress of cancer research – rare diseases strongly remind us how differences are crucial from an epistemological standpoint. Diversity has to do “with both health and disease, that is, human beings are different both when they are healthy and when they are sick” (Gabbani 2013, p. 37). In other words, the status of “being an individual” is not a provisional, but a permanent one. The patient is not an “undifferentiated being”, and both medical research and clinical practice cannot but acknowledge it. Medical doctors are therefore asked to act “by interpreting cases in light of rules, revising the rules in light of cases” (Montgomery 1991, p. 47) they are faced with – including, and perhaps above all, cases of rare diseases.

7.2. Bioethical issues

Rare diseases, considered from a bioethical perspective, raise moral dilemmas and complex problems of social, distributive and allocative justice that can be traced back to, in summary, to three main issues (Barrera, Galindo 2010). The first question relates to an empirical framework that highlights the unbalance between the needs of patients with rare diseases and their satisfaction (unmet needs) that is, between the number of people with rare diseases and the truly effective treatments available. Here the most relevant moral dilemmas concern the “difficult choices”, that is the access to the administration of not only experimental but also not validated therapies, the so-called “compassionate use” of drugs and treatments, which represent the only available alternative, thus highlighting the need for an effective, transparent and therefore ethical approach to therapies.

The second aspect concerns the issues of social, distributive and allocative justice, therefore the procedures and criteria of sustainability, as regards the distribution and access to public health resources. Since it is impossible to guarantee everything to everyone, in principle one should at least consider the moral imperative of guaranteeing “everything that is effective for all those who need it”, as each and every patient has the right to be treated equally. On this side, there are many issues to be solved, which affect new drugs and innovative therapies as regards clinical development, the ethics of experimentation and market access (Juth 2017). The third question concerns the non-negligibility of the rights-based approach in health policy choices. Here, in fact, there is the need for a governance that, at national and international levels, is structured according to ethical criteria and legal instruments aimed at guaranteeing the right to health for all, through measures and guidelines of principle in line with the Declarations of Human Rights (UN 2007) and with our Constitutional Charter (principles of equality, solidarity, dignity and development of the person).

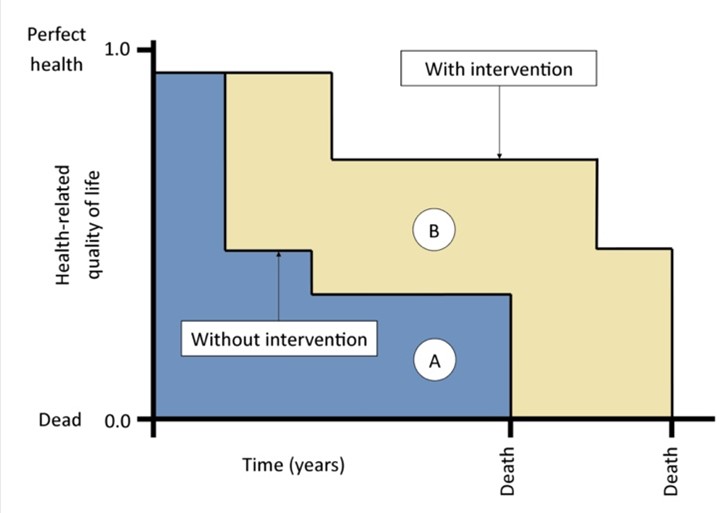

Regarding the first question, the main ethical issues concern the freedom and right of access to therapies which, although not yet authorized, have at least entered the trial phase and for which clinical trial results are available. In fact, in most cases, orphan drugs are available, or rather, drugs for orphan diseases that are rare diseases, which, due to the high testing costs, see pharmaceutical companies usually reluctant to develop them according to normal market conditions. On the other hand, when available, treatments and drugs for the treatment of rare diseases are very expensive even if their efficacy and safety in many cases are not documented. For these reasons the so-called “orphan” interventions are often discouraged compared to the more conventional ones which, although limited in efficacy, nevertheless apply to larger patient populations. The QALY (Quality-Adjusted Life-Year) is the most used model to establish the value of a drug and is used to measure the patient’s quality of life in reference to a treatment (Fig. 12) (Williams 1996).

The cost of a therapy, in relation to the QALY, represents a cost-effective measure to establish the convenience of a treatment compared to others; however, the value generated by QALY is purely statistical and is based on an overall calculation, which does not take into account the specific conditions of each patient interested in the treatment. This has clear ethical implications that affect the adoption of a mainly economic and utilitarian logic based on the sole criterion of cost-effectiveness analysis. In fact, the adoption of an utilitarian logic would not ensure the right balance with fundamental bioethical principles, namely the principle of charity, oriented to always act for the good of the patient, and the principle of justice, oriented to the protection of equity in health (Beauchamp, Childress 1999). Such principles aim at focusing on the health of individuals and not only on the maximization of general well-being. If we move towards the adoption of an ethics that goes beyond the economic data and the utilitarian perspective, we cannot separate the cost-effectiveness measures from a more specific attention, for people suffering from rare diseases, and from a joint commitment to the promotion of their state of health, in accordance with the aforementioned bioethical principles of care.

Regarding the second question, the issues of social justice in this area intersect the ethical requirement of health equity and the concept of the highest attainable standard of health. These are two aspects that may affect the possibility to take decisions on the issues of distributive and allocative justice by assigning everyone the same share of resources. This is a tension that, in the field of health, requires to take into account the different natural and social distribution of diseases and psychophysical deficits, therefore the different degrees of intervention, to ensure that each person enjoys the highest level of health attainable. This is particularly evident where the research and development of therapeutically effective drugs for rare diseases are still debated in the public health system, since they would require a sizable investment that can be perceived as contrasting with the interests and the right to treatment of all other citizens, affected by non-rare pathologies (Rai 2002). Here it is useful to underline, in relation to the epistemological framework illustrated in this chapter, that the contrast between rare diseases and common diseases has gradually become more nuanced, in public and medical-scientific representations. In this regard, it has been demonstrated how certain orphan drugs constitute a therapeutic potential also for non-rare diseases, highlighting the usefulness of rare diseases for understanding common diseases (Stolk et al. 2006; Wästfelt et al. 2006). These issues lead us to consider the last aspect about the relevance of the rights-based approach (Daniels 1998): it must be said, in fact, that patients with rare diseases have the same right to treatment that is exercised by other patients with non-rare diseases, a right which, in this case, is expressed both as a “right to effective treatments” and as a “right to hope” in the development of new possible treatments, thanks to the progress of pharmacological research. The two rights above are enshrined in the Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, according to which “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being” (Callahan 1973).

In conclusion, rare diseases represent a public health priority recognized, at least formally, within a European and international regulatory framework, in which the governments of the EU countries are engaged. However, the rare disease field still poses an ethical, political and social challenge, where scientific research and clinical practice increasingly need to involve not only patients, doctors, researchers, but also different stakeholders, including companies, legislators, politicians and health professionals, in order to make scientific knowledge and clinical practices accessible to patients and families, through transparent and inclusive processes, such as national and international networks (Mikami, Sturdy 2017).