6. WHAT IS THE COST BURDEN OF RARE DISEASES?

Marianna Cavazza

When faced with the question “What is the financial burden of rare diseases?”, one may wonder what the differences are for this specific area compared to the care load and volume of resources absorbed by the most common diseases. Indeed, a significant lower frequency of cases of these pathologies entails an equally substantial greater effort, not only in terms of knowledge, but also of time and resources. A study conducted between the USA and Great Britain in 2013 (Hendriksz 2013) showed that, aside from any innovative pharmacological treatments, not always present in all rare diseases, there is actually a substantial increase in costs in the daily treatment of patients with rare diseases: in the case of Great Britain, an average of £ 7,000 more per year per patient was estimated. In particular, it was found that not only the diagnosis takes an average of five or six years, due to the two or three failures that frequently characterize this phase, but that even single specialist visits are always longer compared to the other more common pathologies. Another aspect to consider is the number of clinicians on average involved in taking care of these patients. In the UK there are on average eight clinicians, a much greater number than for those patients suffering for example from rheumatoid arthritis or from cardiovascular diseases (Hendriksz 2013).

Despite this evidence, attention to the cost incurred by patients with rare diseases, their families and health systems has only grown in recent years. A search with the keywords “rare disease” and “cost” recently carried out on PubMed, one of the main search engines of medical science, revealed that more than 70% of the 244 results have been published in the last six years. The interest first focused mainly on the drugs available for the treatment of these pathologies, their cost and the methods of access to the market, foregrounding the role and burden that the paying third party invests in such situations (Zamora et al. 2019). This is of course a crucial aspect, especially when a new drug therapy is identified for a disease once untreatable; however, on the other hand, it is not the only element to be considered to address the cost dimension in the rare diseases. Thanks perhaps also to the increase in life expectancy recorded for some rare diseases (Franchini, Mannucci 2017; Janssen et al. 2014), in recent years we have begun to overcome this limited perspective and have started to not only consider the financial burden sustained by third-party payers, but widened the analysis to patients, their families and the society as large.

This broadening of perspective has, in turn, led to greater attention to the impact of the resources engaged in the treatment and assistance of people with rare diseases, not only in terms of clinical results, but also in the patient’s quality of life and that of their caregivers. Finally, it should be emphasized that this perspective is also present in a document of recommendations by the Group of Experts on Rare Diseases of the European Commission (CEGRD 2016), which highlights the need to consider and address the needs of social assistance, and in the management of daily life required by many patients with rare diseases.

In this contribution, we review the approaches and tools that have accompanied the above-mentioned evolution of the cost analysis of rare diseases, and the results obtained so far.

6.1. Approaches and tools for analysing the costs of rare diseases

In general, the estimation of costs in healthcare requires careful attention to two key aspects of the analysis, and this is even more true for rare diseases, as we will see. On the one hand, it is necessary to carefully evaluate the perspective that is adopted in identifying the costs to be estimated; on the other hand, it is necessary to interpret the result obtained, considering whether the resources consumed, and the related costs incurred, have or have not produced the expected result in terms of improving the patient’s health and/or level of quality of life.

Regarding the first aspect of “perspective”, in this context we refer to the point of view of the “proprietor” of the resources used, or to which these resources are attributable: if we consider, for example, a treatment that requires a phase of hospital and territorial assistance, a survey of costs in the perspective of the hospital includes resources exclusively attributable to the latter, such as hospital medical and health personnel, beds, and drugs administered during hospitalization. The same applies if the prospect of territorial assistance is adopted. It is therefore the perspective of the National Health Service (SSN) or Regional (SSR) – that is, of the paying third party – that is adopted to reconstruct all the phases of a treatment and the relative assistance provided by the different sections of the public health system, in addition to the related resources used by the latter. This approach excludes resources not attributable to the NHS, such as, for example, any travel costs incurred by the patient, the purchase of goods and services not covered by the NHS, or even the informal assistance provided by the family members or by other non-professional people, always not attributable to the NHS. These items will, however, be included when the patient’s perspective is adopted. Finally, we must consider the perspective of the society. I make reference to the society in terms of community which allows us to understand the resources committed by the NHS and individual patients, but also the “burden” of the so-called loss of productivity that the community faces in terms of any disability pensions for patients, and/or early retirement and with a lower tax contribution capacity by both the patients themselves and the family members who provide informal assistance (Drummond 2010).

It is clear how the perspective adopted, in the context of a cost survey, has a decisive impact on the final result, and how the choice is linked to a series of elements such as the object and purpose of the analysis, the information sources that can be used and the resources available to carry out the analysis itself.

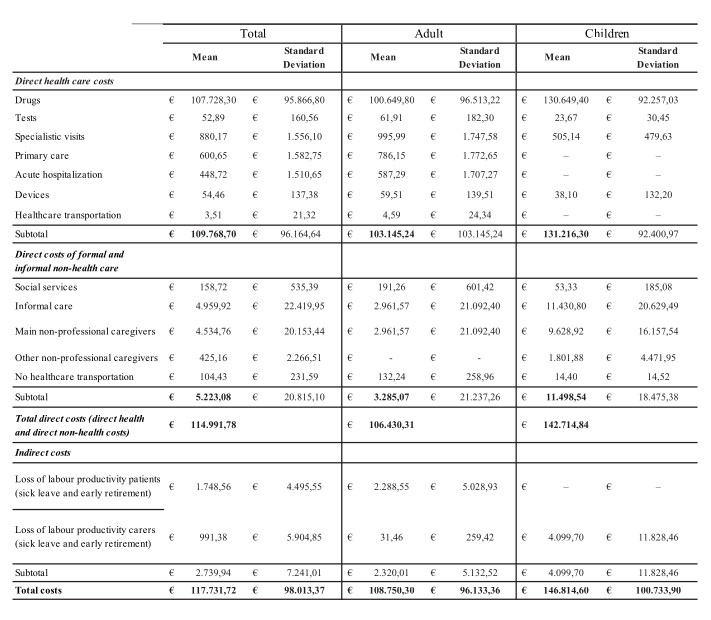

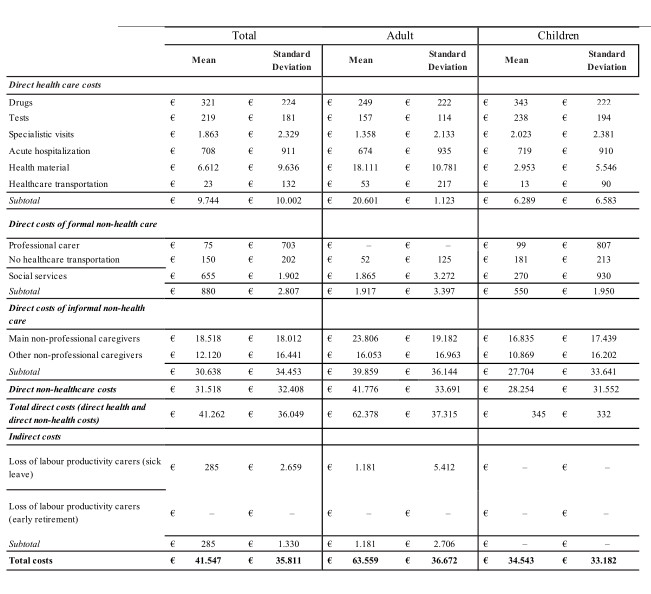

In the case of rare diseases, the most effective perspective is that of society, since most of these are diseases that entail high treatment costs, with repercussions on the public as the paying third-party, and/or highly invalidating with high burdens both for the family in terms of assistance and for society with respect to the loss of productivity (López-Bastida 2016). For example, a pathology such as haemophilia is generally characterized by the prescription of particularly expensive drugs (90% of direct healthcare costs) and could lead to greater focus on the perspective of the paying third-party, although the increase in life expectancy is also increasing attention on other resources and related costs (Kodra et al. 2014). On the other hand, in the case of a patient suffering from a highly disabling pathology such as Duchenne, the consumption of drugs is irrelevant and health services are very reduced, as opposed to the care load generally provided by the patient’s family (Cavazza et al. 2016) (see Figs. 10 and 11).

© 2016.

Given this context, the field of rare diseases increasingly uses a new interpretation of a traditional cost and benefit analysis tool, such as the cost of disease (Cost of Illness, COI) (López-Bastida 2016). It allows us, in fact, to provide an exhaustive description of the social burden on the community, identifying all the actors actually involved, highlighting the predominant cost items (for example, drugs or informal assistance) and analysing the origin of any cost variability attributable to the different contexts and organizational structures (Tarricone 2006).

The second key element, namely interpreting the results obtained from the cost analysis, is based on the assumption that examining the monetary value of the resources on average consumed for the treatment and assistance of a patient suffering from a given pathology certainly provides important indications, but only tells part of the story. In fact, the next step, to fully represent the actual value of the costs incurred, is the comparison of the latter with the results of the services for which the valued resources were used (Drummond 2010). In this perspective, the main tool to be used in the field of rare diseases is quality of life in relation to the state of health (Health-Related Quality of Life, HRQoL) (López-Bastida 2016). This is a “reinterpretation” by the medical science community of the notion of quality of life, further elaborated by social sciences and psychology: specifically, among the various determinants of quality of life, only health and related aspects are considered. This approach, therefore, allows us to remain within the perimeter of the medical mission and to examine the aspects of daily life that can actually be modified by medical interventions. Therefore, the HRQoL provides indications, based on the patient’s perception and their objective functional capacities, about the level of physical, mental and social well-being attributable to their state of health (Ierardi et al. 2010). These surveys can be carried out using a wide range of pathology-specific or general scales; among which one of the most widely used is the EQ-5D family of scales together with Zarit Burden interview instead used to assess the impact of informal assistance on the quality of life of caregivers.

6.2. Results

A large-scale application of these approaches and tools was provided by the Social Economic Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Rare Diseases in Europe (BURQoL-RD) project, promoted from 2010 by DG SANCO of the European Commission, to detect the social burden of ten rare diseases (cystic fibrosis, Prader-Willi syndrome, haemophilia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, epidermolysis bullosa, fragile X syndrome, scleroderma, mucopolysaccharidosis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and histiocytosis) in eight countries of the European Union (Bulgaria, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain and Great Britain). The approach based on the cost of the disease revealed, within each pathology, a strong variability in terms of costs, attributable to the different institutional and non-institutional organizational structures, to the different components of formal and informal assistance provided, as well as to the different level of accessibility to drugs. Equally variable is the HRQoL of patients and their possible caregivers, also following the different volume of resources deployed by health institutions and society (López-Bastida 2016).

Some analyses carried out side by side with the BURQoL project have confirmed that, in general, a greater consumption of resources, and therefore a higher cost, translates into higher HRQoL levels. A more specific examination of this report was therefore carried out with respect to the Italian population of haemophiliac patients, always enrolled in the context of the BURQoL project (Kodra et al. 2014). It was observed that an increase of one point on the measurement scale of the HRQoL, using the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS tools, entails a decrease in the costs of the disease (€ 217 per year) if we exclude the cost of medication. Although the latter represent the most significant cost item for this pathology, the result must be read in the context of the increase in life expectancy of haemophiliac patients in recent decades. In fact, a further analysis of the relationship between the trend of costs, always excluding drugs, and age indicates that the trend is the same as that of the healthy population, with an increase in the first years of life (0-4 years) followed by a steady decrease in subsequent years, up to 46 years of age, when costs start to rise again.

6.3. Conclusions

Returning to the initial question regarding the financial burden of rare diseases, the answer is that they generally cost more than other more common chronic diseases, as evidenced by the above data (Hendriksz 2013). The question becomes, therefore, how much more do they cost and the answer – always feared by policy-makers and typical of complex situations – is: it depends. It depends, of course, on the pathology and resources it requires, as well as on institutional and non-institutional organizational structures, and so on. What certainly combine these pathologies is, however, the complexity of monitoring and managing them. Hence we need to take on the perspective of society to be able to take into account all the actors involved and the resources actually consumed. Finally, it is important to continue to deepen the analysis of the relationship between the costs incurred and HRQoL, since it is probably the best way to answer the question of how much rare diseases actually cost.