4. THE BEFORE AND AFTER

Maura Foresti

“Rare” is a word full of implications when combined with “disease”; it brings with it a range of issues, such as isolation, loneliness, discrimination, chronicity, shortage of competent professionals and scientific knowledge, uncertainty of prognosis and orphan drugs. If we add the genetic component, the implications also run towards generativity and reach the very definition of human being, touching on themes of considerable complexity.

Thus we can understand how communicating the diagnosis of a rare disease to a carrier, or to their parents if they are children, is a moment universally recognized by doctors as difficult. In clinical experience, we often find in patient reports that even years later the communication of a rare genetic condition can take on various traumatic characteristics. The many clinical testimonies collected could be well summarized as follows: there is a before and an after.

The scientific literature of the last decades has been very interested in the topic (Starke et al. 2002; Liao et al. 2009), highlighting the highly stressogenic and psychopathogenic potential of receiving such delicate information, capable, capable of capsizing one’s world and life expectations for the future: it is documented that such an experience can cause various psychopathologies from post-traumatic stress disorder to anxiety-depressive disorders.

Beyond the many useful indications that can be found in the literature (summarized in the form of a list in the next paragraphs) on how to communicate this type of information, it is important to clarify that it is not possible for this information to be painless. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary that the communicator anticipates accepting the natural reaction of pain, giving space and time to the people who receive it in order to integrate it into their mindset and planning. However, the experience of the human being learning such a truth about him or herself or about a child is sometimes pain of devastating proportions. We need to meet this pain head-on in order to fully understand its challenge. Sometimes even operators try to defend themselves from this encounter, for the completely unfounded fear of being overwhelmed. It is, in fact, a matter of handling a “highly toxic” material, as the scientific literature on burnout has clearly highlighted.

From this premise that it is not possible to communicate this type of information without causing intense pain, it follows that the goal of diagnostic communication should not merely be passing on the information, but offering the people who receive such information the necessary support to be able to integrate it, and achieve a new state of balance. In short, if we know we must inflict a necessary injury, we will have to be careful to avoid possible “infections” and complications, not to feel like bad healthcare workers and not to become targets of intense negative feelings that are difficult to bear.

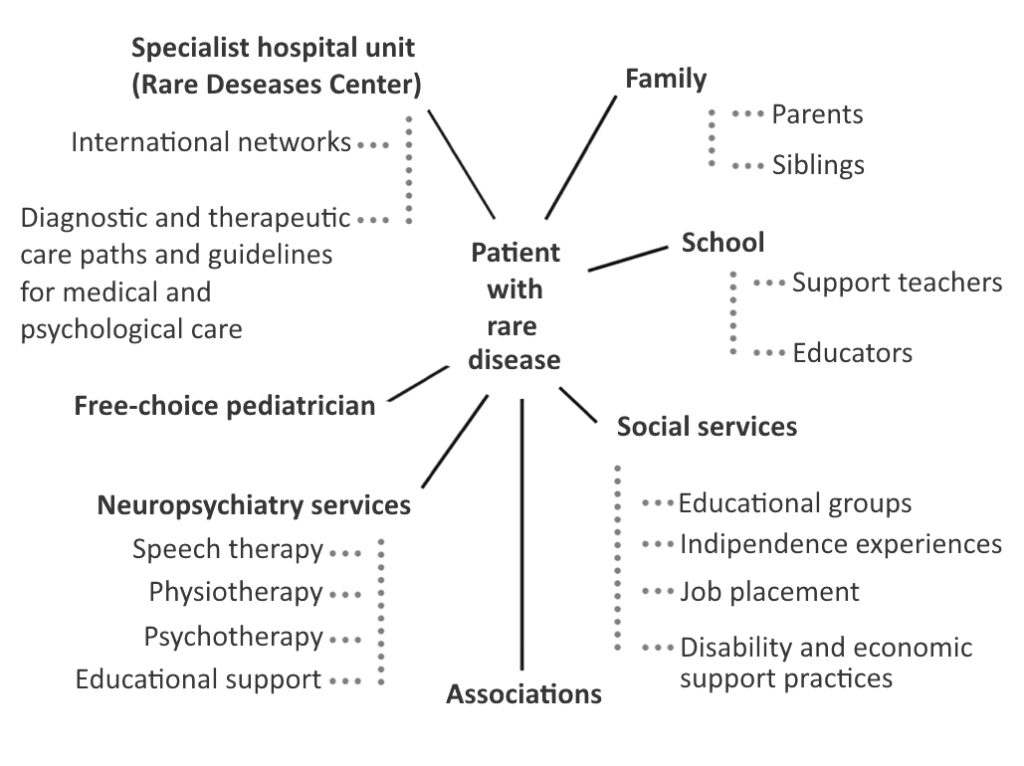

Here then are the general conditions that the literature has come to describe to achieve adequate communication, that is, communication capable of preserving the health of all the actors involved (Fig. 8).

The communication should:

- take place in a dedicated place, reserved for this activity and, above all, it should be transmitted without haste and with adequate time provided;

- be given to the interested party together with a relative or, in the case of minors, to the parents together;

- be accompanied by the scheduling of at least one further explanatory meeting, within a short time;

- provide psychological support/consultation;

- provide a contact number to refer to from then on for information on the condition that has been diagnosed;

- be accompanied by offering information brochures, contacts with other carriers and/or with associations of patients or parents;

- be provided with the collected input shared by a multidisciplinary team and a network of professionals.

Furthermore, in the case of minors, the communication should set in motion an “internal debate” between parents on how to communicate with the child about the diagnosis as they grow and develop. In this regard, in fact, there is some literature on the difficulties of parents in communicating to their children their chronic conditions, with far-reaching consequences for the way in which the future adult will manage and elaborate his or her own clinical condition (Sutton et al. 2006; Suzigan et al. 2004). With regard to this last point, often the advice or intervention of a psychologist, an expert in the developmental age and rare diseases, is necessary.

Two phases of life pose specific challenges that require further precautions: the prenatal phase and adolescence.

4.1. Prenatal diagnosis

Many studies have tried to highlight the serious threats implicit in prenatal diagnostics stemming from two factors: The first is connected to the fact that pregnancy is a moment of great delicacy for the psyche of a future mother, who is trying to prepare herself, both in practice and through fantasies about the unborn child, to welcome a new human being with whom a relationship already exists. The second relates to the fact that the relationship between the infant and its caregivers is a foundation for the development of every human being. In fact, in taking care of the newborn, adults will carry out the crucial functions of imprinting, activating and conducting all its mental development (Camaioni, Di Blasio 2007).

In the prenatal phase, fantasies take on a much greater power than in other stages of life. In this phase, the words spoken by doctors are powerful as they affect these parental fantasies about the unborn child: in clinical psychological practice it is a daily occurrence to receive testimony about how the information received is indelible and, unfortunately, also easily misunderstood.

Countless studies, starting from the Second World War, have highlighted the crucial importance of early care experiences, as well as the importance of adults’ expectations and fantasies that attribute meaning to the experience of the newborn (Winnicott 1970). That is why a meeting should always be provided to communicate the outcome, positive or negative, of a prenatal diagnosis: the mere fact of being contacted by phone already translates into a negative communication, bringing hours or days of nameless anguish. Thus couples who undergo such diagnostic procedures should be prepared psychologically, giving them an opportunity for preventive health protection in which they can reflect on their parenting adventure and their willingness to receive non-positive news from the diagnostic procedure itself. This is why, finally, in the event of a prenatal diagnosis of rare disease, it is always necessary to offer the parental couple, after consulting with the geneticist, counselling with paediatricians who are specialists in the condition and with an expert psychologist.

4.2. Diagnosis in adolescence

Another critical moment that requires special attention is adolescence. It is a phase of development that in recent decades has attracted a lot of attention from society (keeping in mind that adolescence did not exist as a category until the beginning of the last century) and psychological science. The pubertal phase that characterizes its beginning – second in importance only to the stages of embryonic and perinatal development – is the era of human development characterized by the most significant transformations that concern the body (biological maturation), the mind (cognitive development) and behaviour (relationships and social values). The discovery of a rare disease, at this stage of development, can be much more difficult to accept and can trigger very complex reactions to contain and elaborate the information (Sawyer et al. 2003). The intervention of an expert psychologist in the developmental age is often necessary and must include the adolescent as the main interlocutor although the family context must also be considered, even if in most cases this remains separate from the individual patient treatment.

4.3. Diagnosis process

The most common defences against negative news are well-known to doctors, who face daily difficult diagnostic communications: disbelief (requests to repeat tests to be sure they are not a mistake), cognitive confusion and denial (some time after the communication, the patient claims that he or she has not been informed of a part or all that was actually communicated to them, or has misunderstood crucial parts of the communication) or escape (patients put aside the diagnosis, do not access the proposed follow-up, forget to book prescribed exams, do not talk to anyone about the diagnosis received). These defences prevent the healthy course of processing the communication from taking place. This process foresees that, by going through the pain brought by the negative truth, we will get to integrate it into our world of knowledge and to welcome the treatments and resources proposed. It is these defences that also explain the frequent isolation of many families and many rare patients.

The course of processing the diagnosis is activated slowly after communication and requires a variable time; it is necessary to check that it starts correctly and, in the case of rare conditions of developmental age, it must be monitored over time (D’Alberton 2018).

First of all, as anticipated, it is necessary to plan at least a second meeting after a diagnostic communication in order to be able to ascertain that a processing has started adequately. If this has not happened, the necessary specific psychological interventions must be put in place (psychological counselling, discussion groups led by a psychotherapist, targeted psychotherapy courses). Therefore, if the process has started correctly and the pain of the news is contained, it will not be necessary to arrange other interventions; if, however, the people who received the news are suffering acutely, it will be necessary to offer them a path of some talks that unfold over time and that accompany them in containing and thinking through that great pain that they cannot manage to tame. In short, we can say that when the communicated rare condition heavily impacts the quality of life or future expectations, when anxious or depressive symptoms occur, when a teenager shows an angry or withdrawn reaction, or abandons his or her vital plans, it is necessary to intervene with appropriate psychotherapeutic tools; when the pain of a parental couple risks damaging the relational developmental, because it produces a dysfunctional interaction with the child, a specific intervention must be offered that reactivates the mother/father-child relationship (the so-called participatory consultation, see Vallino 2009); when feelings of guilt or shame damage the relational life of a person with a rare disease (or of his or her family in the case of minors) some psychological interviews must be offered to address these psychopathogenic feelings and appropriately provide contacts with associations, group meetings conducted by a professional, or mutual help, which can make them feel less alone, unique and at fault.

Since the acceptance of certain painful truths is a great challenge for every human, we can conclude that the diagnostic communication of a rare disease should be understood as a multidisciplinary process – involving doctors, psychologists and associations – rather than as a punctual event that ends in a mere communicative transfer of information, and should take into account the particularities of the diagnosed condition, the context and the moment of development or life of the subject, preparing specific pathways for pathology and for the delicate stages of development described above.