V. THE CHENGDU CASE: STARS AND TRENDS

Martina Merenda

Chengdu is the capital of the Sichuan province, located in southwestern China. This territory is also known as “The Land of Abundance” (tianfu zhi guo 天府之国) due to its mild climate and generous harvests:

Thanks to its fertile soil, humid climate and abundant rainfall, and particularly since the construction of the ancient Dujiangyan irrigation system during the Qin Dynasty, Chengdu has been named “The Land of Heaven” (or abundance). Its people know no anger as they can control drought and humidity. For this reason, Chengdu is the ideal land for artistic growth – Fan Sack explains. (Interview, 2019)

With an ever-growing population of about 14 million, in the last few years Chengdu has undertaken an extraordinary process of development, constructing numerous large flyovers, countless skyscrapers, shopping centres and an underground network that covers the entire city. Despite its strong economic, political, and industrial development, the city still retains instances of traditional architecture, local food and culture that preserve its historical Chinese atmosphere and typical Oriental flavour. Chengdu is in fact one of the 24 cities the State regards as forming part of China’s historical and cultural heritage. The dialect spoken in Chengdu is Sichuanese, also called the “Sichuan dialect”. To be more precise, however, and to distinguish between the diverse accents spoken in the areas of Sichuan, it is preferable to speak of a fully-fledged Chengdu dialect.

The city’s name has never changed over the centuries, and since its founding Chengdu has always been the most important city in the Sichuan Province, of which it has been the capital for more than two millennia. The first ethnic group to settle in the territory about 5,000 years ago was the Shu (221- 264), which established its kingdom along the Chengdu Plain, creating the greatest civilisation Sichuan has ever witnessed. Chengdu has hosted literary giants like Sima Xiangru (around 179-117 BC) and Yang Xiong (53 BC-18 AD), authors of descriptive prose and poetry from the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). Likewise, it has been the artistic homeland of important literary figures, such as Li Bai (701-744) and Su Shi (1037-1101), the most eminent poets of the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties respectively, along with Zhao Chongzuo (934-965), the Shu-era (221-264) poet and author of Among the flowers, the first ci 词 anthology in Chinese history (Jiang, 2021). Ci is a Chinese poetry genre, also known as changduanju 长 短句 , (“made of verses of irregular length”) and shiyu 诗 余 (“comparison, outline poetry”). Ci were originally composed to be sung following a precise rhythm, rhyme and tempo.

Du Fu (712-770), another important Tang-dynasty poet, was also based in Chengdu and lived in the “Dufu Cottage” or “Dufu Hut”, now converted into a museum dedicated to his life. Wang Wei (700- 761), the administrator of Chengdu during the Han dynasty, established the first local public school, whose location has remained unchanged for more than 2,000 years (Pang 2021): the Shishi zhongxue 石 室 中 学 (Shishi Institute). As early as 938 AD, Emperor Meng Chang (919-965) founded China’s first royal art academy in Chengdu. The decorative style of the palace that housed it was achieved through flower and bird painting (hua niao hua 花鸟画), inspired by the founding fathers of this technique: Xu Xi (886-975), Huang Quan (903-968) and his son Huang Jucai (933-993) (Johnson, 2017). Flower and bird painting is distinctive of 10th-century China. Xu Xi and Huang Quan were masters of two different schools: the first was led by Huang Quan and marked by the “outline” brushwork method, with meticulous, bright coloured fillings. The second was led by Xu Xi, and favoured techniques associated with ink wash painting (ibid.).

Sichuan’s capital is also home to numerous Buddhist temples. These are places not only devoted to prayer but also to recreational activities. Their courtyards and gardens become gathering places to eat vegetarian food, drink tea, play cards, sing local opera songs, or challenge each other at mahjong. A typical example is the Wenshu Monastery, the best-preserved temple in the entire city and the headquarters of the Buddhist Association of the Sichuan Region and the City of Chengdu. The Monastery’s ancient art treasures are its crowning glory: more than 500 paintings and calligraphy works of famous artists have been collected here since the Tang and Song dynasties. Its chambers also house precious relics, and about 300 Buddha statues made of various materials, including iron, bronze, stone, wood and jade (Tay 2019).

An important part of the city’s culture is the Sichuan Opera, one of China’s oldest regional operas. Chinese opera differs from its western counterpart in several ways, but mainly in the fact that in China stories are rarely told from beginning to end, with theatre-like dialogues or monologues (except perhaps in the Peking Opera). Instead, it consists of stand-alone parts which may be accompanied by circus performances (acrobats, fire-eaters and clowns) or, like any other opera in the world, by fully sung narrative parts. Sichuan Opera’s chief feature is its circus elements: the actors are often experienced acrobats, excellent illusionists, skilled fire-eaters or clowns – a category of performers in which the city of Chengdu excels. The mesmerising art of “face changing” or bianlian 变 脸 , which involves the use of multiple masks (layered on top of each other), is practiced at outstanding speed and was developed about 300 years ago, during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736-1795) of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). The techniques used to swap these masks are a closely guarded secret, handed down by theatrical families from generation to generation. In ancient times, the faces of the performers would change colour by blowing powder on them, which would adhere to their skin, moistened and greased by makeup. Modern-day actors use painted silk masks, which cover the entire face and can be layered up to a maximum of 24. Today’s actors can change up to 10 masks in 20 seconds, and detecting the precise moment when the mask is swapped is virtually impossible.

Contemporary artistic turmoil

The Chengdu art scene has only flourished in recent decades due to the opening of contemporary art galleries and public museums. Chengdu’s atmosphere differs greatly from that of the bustling cities of Beijing and Shanghai, and it presents a more regional insight into contemporary Chinese art. Two examples are the Sichuan Art Museum, the largest professional art gallery in southwest China, with six exhibition halls housing works by classical and contemporary Chinese artists and boasting a collection of nearly 8,000 printed works, and the Wuhou Art Gallery in the garden of the historic Wuhou Shrine, founded in 2013 and committed to preserving and promoting art and culture in the region.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chengdu (MOCA) is another vibrant example of artistic excellence. Opened in 2011 within the Chengdu Tianfu Software Park, MOCA houses entire collections of contemporary artworks from across China and around the world, as well as numerous collections by western artists, including Tony Cragg and Picasso. The Thousand Plateaus Art Space is a professional gallery founded in 2007, also committed to presenting and promoting contemporary Chinese art. Its exhibition hall and the room dedicated to video projections are primarily intended for researching experimental works and projects pertaining to China’s contemporary art and culture. On top of that, the gallery actively carries out national and international cooperation projects. Particularly noteworthy within the Chengdu cultural scene is the Chengdu Art Academy, one of the most preeminent in the Sichuan capital. Founded in 1980, it is the first nationwide professional art organisation established by the government and is involved in the creation of paintings and calligraphy, art theory research and academic communication. The academy currently coordinates cultural exchanges and hosts delegations of artists, art historians, renowned calligraphers and painters.

Given its artistic and cultural scene, graffiti art spread in Chengdu much more rapidly than in Beijing and Shanghai, where authorities exercised greater control. “In Chengdu there are plenty of places where graffiti can be brought to life. As far as I am concerned, every main street, public place or empty space is suitable for graffiti pieces”, says Gas (interview at Creative Warehouse, 2016).

One of Chengdu’s most eye-catching and distinctive graffiti sites is Fuqing Road (Fuqing Lu 府青路). This street is almost 200 metres long, and its red brick walls are decorated with splendid graffiti. In addition to traditional bright red and yellow dragons, it is possible to admire depictions of the cars, buildings and bridges of Chengdu, along with murals dealing with the contemporary themes of industry and progress, and general reflections on city life (Luo, Gao, 2018).

Another example of graffiti invasion in the city is a 400 metre long construction site on Dongda Road (Dongda Lu 东大路), which has been entirely covered with murals and has become a particularly appealing and popular destination for young graffiti enthusiasts. Subtle lines, intense colours and marked creativity make this site a new “art sanctuary” located in the southwest of the city. Among the most frequently represented themes are traditional elements such as giant pandas and cranes, together with abstract concepts and indefinite lines that bring colour and enliven the district, previously referred to as grey and dull by its residents (ibid.).

The most fascinating art space of all, entirely dedicated to graffiti, is a small area nestled in the heart of the city and hidden by residential skyscrapers in the urban district U37 Creative Warehouse (Fig. 13). This is a gathering place for artists of all kinds, from writers1Writer (tuyazhe 涂鸦者 / penzi 喷子 / tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家 / xieziren 写字人) – An artist who executes graffiti mainly based on lettering. to musicians, literature enthusiasts and lovers of eastern culture.

Given its geographical location nestled among the mountain ranges, the city of Chengdu offers a quiet, somewhat protected lifestyle. It possesses numerous peaceful places, in absolute contact with nature and its elements. Buddhism and Taoism fully embrace the city’s daily culture, and such rich traditions allow artists to cultivate their passion peacefully and serenely, immersed in their inspirations – Fan Sack explains. (Interview, 2019)

Chengdu has several art centres and clubs. Every year city life is enriched by new festivals and events, so numerous and disparate that “it becomes almost impossible to list them all” (ibid.). Thanks to the huge success of hip-hop2Hip-hop (xiha 嘻哈) – A cultural movement that emerged predominantly in the Afro-American and Latino communities of the Bronx in New York, in the late 1970s. The four main aspects or elements of hip-hop culture are speech, music, movement and sign: MCing (shuochang 说 唱), or rap music introduced by Afro- Americans (MC is the acronym of Master of Ceremony); Djing (dadie 打 碟), introduced by Jamaicans; graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) and breakdance (diban wu 地板舞 o pili wu 霹雳舞), introduced by Puerto Ricans. culture and the increasing popularity of graffiti, every year new rappers and young writers approaching the world of street art flock to this city. The Chengdu International Landscape Graffiti Festival held on 19 June 2019 showed vividly how different artists and artworks can coexist in a single setting. The event brought together a vast number of renowned artists from all over the world to create 3D graffiti at 14 tourist spots in the city, including Chunxi Road, Taikoo Li and Lan Kwai Fong (Yaobin, 2019).

In essence, Chengdu is a suburban city with a flourishing graffiti culture. Among the many graffiti writers operating here, special attention should be paid to Gas and Fan Sack, considered by the public and the media as the two best-known and internationally recognised writers. Their conception of graffiti is rooted in very different perspectives: Gas is a Chengdu-based graffiti writer who works tirelessly in the city and feels the call of his native culture; Fan Sack was born in Chengdu, where he began his artistic career as a graffiti writer, but currently lives and works in Paris with the goal of spreading his art – which has shifted to a more figurative language – all around Europe. His works range from graffiti writing to street art3Street art (jietou yishu 街头艺术) – A mass media term that tries to define all the art forms performed in public places, often illegally and using the most diverse techniques. Born from graffiti writing, it has developed and evolved into different practices over time: sticker art, stencil art, poster art, video projections, sculptures, installations and performances. and painting, and he is the emblem of a migrant writer who has managed to maintain a purely eastern identity within his pieces.

The “eastern breath” of Gas

Chen Zhipeng 陈志鹏, better known as Gas (in Chinese Qi 氣), but also by his life-long nickname Shui Gui 水 鬼 (Water Ghost), was born in 1989. He is originally from Chongzhou, a town not far from Chengdu. His Chinese tag4Tag (qianming tuya 签 名 涂 鸦) – The pseudonym, stage name, or code name that every graffiti artist, mc and breaker uses to distinguish themselves, to stand out and highlight their presence in the city. Being the most basic form of graffiti, created with spray cans or markers, the tag is the backbone of the writing phenomenon. The evolution of the tag represents the personal style of its author. All pieces, even the largest, most colourful and elaborate ones, remain, in essence, signatures. The activity of marking a surface with a tag is called tagging-up, while tag bombing is the reproduction of one’s tag on a large scale in a certain area of the city. Tags can also be representative of entire groups. Different writers or mcs who join together can decide to use one comprehensive tag, as a symbol of the group (see Crew). with the traditional character qi 氣 is a translation of the word “gas” and comes from the eastern philosophy of tao (Pic. 25).

He explains:

When I started graffiti, I simply wanted to become famous. The first tag I chose was Code321, but after a couple of years I realised that no one would remember me because I was just a “code”. So, I changed my tag to something that could truly identify my work […]. The tao symbol is half white and half black. In the tao, the greater the white, the lesser the black, and vice versa. Qi means “breath”, so for me qi is the “eastern breath,” the essence of everything. The spirit of qi is everywhere, even in this very moment between you and me. (Interview, 2016)

In the history of Chinese thinking, qi generally means “vital energy”. Qi is split into da qi 大 氣, meaning “great energy” or “energy of the macrocosm”, and xi qi 吸 氣, meaning “breath”. Originally, da qi was thought to have condensed and descended, giving rise to the earth – hence rain is the qi of the earth; by rarefying, it then rose, giving origin to the sky – hence wind is the qi of the sky. Human beings, who stand between heaven and earth, have both manifestations of da qi within them: the heavier forms the body, the lighter forms the heart (Pasqualotto 2007, pp. 108-110). Gas’ choice of the character qi as his tag, therefore, has a higher meaning, profoundly bound up with the history of Chinese thinking. The idea of qi is also closely related to another fundamental concept in Chinese culture: the xing 行 (stage, process). The notion of the wu xing 五 行 (lit. the five elements, but more precisely the five processes) describes nature as a set of five founding elements (fire, water, metal, wood, and earth) and as the outcome of their interconnections. By picking these two fundamental concepts of Chinese culture (qi and xing), Gas highlights his intention to infuse his art with the “eastern breath”, starting from his very tag.

The artist came into contact with the hip-hop culture at the age of 12 through magazines and websites, and was particularly inspired by the SUKs (Stick Up Kids). This is a crew5Crew (tuandui 团队) – In hip hop culture, a circle of people collaborating on artistic or cultural projects, e.g., a group of writers or dancers. In graffiti writing, a crew is an organised group of writers who paint together to create pieces. They are usually friends, meaning they share mutual esteem and respect. A writer may belong to more than one crew over time, or even at the same time. The name of a crew is normally an acronym of two or three letters, possibly having multiple meanings. Like tags, crews’ names are often written on the side of the piece, or they form the very core of the piece, with the name of the crew members dotted all around. founded by Cantwo, a writer from the Bronx active since 1983, and the MSK (Mad Society Kings), a crew that operates in various parts of the world, particularly in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Brighton, Bristol, Atlanta, Bangkok, Oakland and Houston. Gas became passionate about underground culture and three years later decided to start his activity. Although he enrolled in an art academy at the age of 19, he does not like to define himself a fully-fledged “artist”, but rather as a writer (xieziren): “I remember when I first picked up a spray can at the age of 15 and started painting on a wall. I would watch the graffiti take shape and be literally in awe” (Charlie 2011a).

Young Chinese writers were still technically novices at that time. Many of them came from art academies and had a purely “scholastic” background and experience. This meant they were able to learn quickly, were great scholars, and were generally highly knowledgeable about art, but they were still unpractised in the field of graffiti:

I think young Chinese people learn fast – progress and industrialization are advancing at an unimaginable pace here – but they lack cultural knowledge. For me it was different. I discovered hip-hop culture at the age of 12. At 15 I embarked on street art by painting on walls, and at 19 I entered the academy. One could say mine was pretty much a reverse path, from the street to the academy. At that point I ended up falling completely in love with the art world, but I was actually already totally immersed in it. (Ibid.)

The essence of qi is everywhere, in the same way as Gas’ intent is to take his tag, and spread his art, everywhere. To do this, he has chosen the Chinese language as the dominant element of his works: he exclusively uses traditional Chinese characters, instead of their modern, simplified form as one would expect from a contemporary writer: “I am Chinese; since childhood, I have always expressed myself through the Chinese language, and therefore I would not know how to shape my art except through my mother tongue. Americans speak American and express themselves in their language, I do the same with mine. I find it absolutely natural” (Interview, 2016).

The work Feng 風 (Wind, Pic. 23) is a clear example of how the Chinese language, and traditional characters in particular, are a recurrent feature of Gas’ works. It demonstrates the extent to which traditional culture is important to him and how much he wishes to spread the main principles of Buddhist philosophy through his art. The piece6Piece (zuopin 作品) – A graffiti painting, short for Masterpiece. It is also considered an enlarged tag executed with spray cans, composed of multi- coloured letters (it’s generally agreed that a painting must have at least three colors to be considered a piece). The term is generally used to distinguish graffiti from simple tags. The piece is the third stage in the evolution of letters, after the tag and the throw-up. consists of the traditional non-simplified feng 風 character, the shapes of which have been reworked and restyled in the spirit of contemporary graffiti. It is painted in a typical 3D style, with three-dimensionality conferred through a thick dark purple outline7Outline (lunkuoxian 轮廓线) – The letter outline, the contour line of the piece that defines and shapes its structure: the outline put on the wall and then filled, or the final outline done around the piece to finish it. Can also refer to the drawing done in a piece book (see Black book) in preparation for doing the actual piece (see Sketch). and fading shades of colour within, ranging from brick red to straw yellow.

The large character is surrounded by several inscriptions: on the top left- hand corner, there is the tag of the artistic-collaborative duo between Gas and Seve (or Seven) from the Beijing’s ABS crew, Hao Qiao 好巧 (How Chill); on the top right-hand corner, the year in which the work was executed (2016); on the bottom left, the title of the work Feng 風, written in non-simplified characters. In the bottom centre is the tag of the KB crew from Hong Kong, with whom Gas often collaborates when in Chengdu. Finally, on the right is the artist’s tag GAS, in Latin letters. The choice of the traditional feng character has a double meaning: firstly, it is one of the 214 radicals of the Chinese language. In Chinese, a “radical” (bushou 部首) is a graphic component within each character that classifies and sorts it in the dictionary index (Abbiati 1992, p. 32). They are interpretive keys that identify the semantic class of each character, and usually retain a certain ideographic value. Secondly, choosing the traditional form of the feng character could be an evident reference to the Buddhist philosophy. As Gas explains, “Buddhist philosophy influences my art, and is the only thing that really represents me” (interview, 2016). In Classical Chinese, the word feng also means “to influence”, “to get someone back on track when he has lost his way” (Arcodia 2008, p. 57), and possibly denotes the artist’s desire to spread his culture and breathe new, contemporary life into classicism. Using traditional characters is a way of recapturing the artistic splendour of Chinese classicism or, more specifically, of its ancient writing system, and revitalising it through graffiti writing.

Although Gas loves painting alone and being totally independent, he also enjoys working with other writers and undertaking collaborations (interview, 2016). When in Chengdu, he often teams up with the KB crew, an acronym for Kong Boys, in which “Kong” stands for Hong Kong, where the crew generally operates. In Buddhism, the meaning of the word kong 空 is associated with the concept of shunya, “bare essence”, or the “emptiness” that softens ideologies, allowing things to be seen for what they are and as they appear, in their pure essence (Arena 2016, p. 14). Another meaning of kong is “free space”, perhaps to emphasise the crew’s desire to fill every possible place with their works. The crew is often bestowed the title of gancai 干 才 (people with special aptitudes and abilities) for their impressive skills. Its exact number of members is impossible to determine since, as Gas explains, writers do not give official interviews: “This is part of the game: you know me, you know who I am because you find my signature on my works, you find traces of me, but you will never see my face. It is difficult to establish precisely who and how many we are. It would be like ‘unmasking’ our identity” (interview, 2016).

In 2009, when street art and graffiti in China were still at their early stages, Gas met He Li, better known as Seven (or Seve), a member of the ABS crew in Beijing (see Ch. III). When the ABS participated in the famous Asian competition Wall Lords Graffiti Battle in Chengdu in 2011 and won the first place (Pic. 13), Gas was the one who presented the award (Charlie, 2011b).

The collaboration between Gas and Seven resulted in the tag How Chill (in Chinese hao qiao 好 巧 , lit. ingenious, skilful). It is possible to get a taste of their joint work in the piece created in 2019 in Kuixinglou (Pic. 24), a famous street in Chengdu where many graffiti artists have left their mark, including Fan Sack. The work is divided into two markedly distinct parts: on the left stands the Chinese word Chengdu 成都, created by Gas in wildstyle8Wildstyle (kuangye fengge 狂野风格) – A complex composition of letters assembled to give a unique shape and dynamic to the piece. In this style, the letters are distorted and superimposed, and sometimes enriched with three- dimensional arrows, tribals, pikes, puppets and other decorative elements that give an idea of movement and confusion. This style can be straight or soft: the first is symmetrical, and the arrows forming the letters draw sharp angles; the second is asymmetrical, and the angles are replaced by curved arrows with rounded points. To increase the perception of depth, in addition to inserting junctions between characters, the entire word structure can be turned into a three-dimensional element. This complicated construction of interlocking letters is considered one of the hardest styles to master and the lettering of the pieces done in wildstyle is often completely undecipherable to non-writers.. The Chengdu 成都 characters are orange, yellow, and white, with black and dark blue outlines that confer three- dimensionality. Dark and light blue shades are used in the background and give the piece even more vibrance and an almost flickering motion, while creating a stark contrast with the right side of the work created by Seven. An S-shaped chain separates the two parts of the piece. On the right, we find the initials LA (Los Angeles), painted by Seven in 3D style, with various puppets9Puppet (tu’an 图 案) – Figurative elements alongside the graffiti. These may be human figures, animal-like monsters, or comic or cartoon characters (see Character). representing figures of the Chicano (or Chicana) community. Chicano is a term Mexican Americans use to assert their identity, and appears in the background of the piece. According to Gas, this American ethnic group is highly valued by Seven. In the 1960s, this community developed a veritable lifestyle and, above all, a dressing style sublimating their desire for social vindication: baggy clothes, flat hats, chains (which we actually find in the piece), watches, and particular tattoos (we see a tattoo studio in the lower right corner). Seven’s images are mostly black-and-white, while the golden outlines of the LA acronym make the letters stand out, enhancing their three-dimensionality and immediately capturing the viewer’s attention. In the upper left-hand corner stands a message in English, alongside a blue clover representing a clear community call: If I had an end in my heart, I would prefer that I should never arrive. The inscription is accompanied by a car whizzing through the clouds. As Gas says, “I had the opportunity to collaborate with brands for advertising campaigns, but that was limited to the purely commercial sphere. It’s not art, it’s business!” (interview, 2016).

Indeed, How Chill represents a collaboration aimed at raising funds to promote the spread of graffiti art. Through commissioned pieces for brands like the National Football League (NFL) and Nike, as well as luxury restaurants and gyms, the How Chill duo invests its earnings in training young writers and spreading underground culture. The main channel through which Gas and Seven conduct this project is Still Writing, a spray paint shop inside the Red Star 35 cultural and creative industrial park in Chengdu. Although the shop has recently been going through a bad spell, the writers are happy to have created a hub where young street artists can collect and purchase materials for their pieces, which they consider a service of the utmost importance. Even though collaborations with big brands are vital for writers and allow them to create a market where they can find the right equipment for their art, Gas has never given up the pure and simple pleasure of painting. To this end, he makes agreements with the government to create open legal spaces where artists can express themselves freely:

In Chongzhou, where I come from, there is a 100-metre-long road covered with graffiti on both sides. I did that myself, perfectly legally. I spoke to the city officials beforehand. They know I am a good person, that I don’t go against the government. That is why I have been granted permission to use the space. Some people are really stingy when it comes to their art, they just want to make money out of it. For me, it all starts with the pleasure of expressing myself. Before making money out of your work, you must improve your skills. This is what I feel. […] The real essence of writing and street art in general is painting so that the public can be entertained and admire what you do. Taking pictures of graffiti and sharing them online is nice, but that’s not the point. I don’t make graffiti to collect images; the primary goal for me is to display them in the street. I want to paint on large streets, I want to fill them with my art. Big corners, noticeable places. I want to take my art to the streets. I hope Chengdu will grow to embrace street art in all its forms. That is what I hope for the future. (Ibid.)

Fan Sack: from graffiti writing to Buddhist-inspired painting

Chengdu’s urban landscape has considerably changed over the last two decades and every year new artists like Pang Fan 庞 凡 , better known as Fan Sack, enter the street art scene. A native of the city of Chengdu, later active in Paris from 2008, Fan Sack started his activity as a writer back in 2003, at the age of 15:

Even when I was very young and couldn’t read, I would flip through books and comics, and the pictures really spoke to me. But I never thought I would become a cartoonist or a writer. Growing up, when I was about 15, I met skaters in Chengdu. Back then this kind of sport was rather frowned upon. I thought it was cool, and there were graffiti pieces as a backdrop. So, I started myself. We were a very small group of five young people in a city of several million, sharing the same tastes and passions. We painted in the streets because, at the time, our culture considered graffiti as vandalism. We had troubles with the police and with our own fellow citizens because what we were doing was absolutely new and obscure to the public. No one had ever seen it before. Until then, our public space, our walls, had been occupied exclusively by advertisements or official government and communist party slogans. (Boraccino, 2019)

The choice of his tag, Fan Sack, dates to his early career: “I have always used this name since the very beginning of my artistic life. When I moved to Paris, I couldn’t help but notice how tags are everywhere; how they are a highly visible trademark of the artists themselves. I thought it would have to be the same for me” (interview, 2019).

Having painted traditional Chinese and oriental-style graffiti from a very young age, Fan Sack declares his passion for street art and especially his desire to expand graffiti through his own Sichuanese culture:

I think creating graffiti was and still is a completely natural process for me. I started drawing and painting when I was only a child. Like everything in my life, it was a discovery, a search for something new to experience. I have always opened my heart and mind to new experiences, and this probably enabled me to build my artistic career […]. Basically, I want to express myself. My mind is full of ideas, and I need to find a way to communicate them to others. I want my graffiti to show the culture of Chengdu, the lifestyle and essence of my city, like the art of drinking tea, eating hot pot10Hot pot is a traditional Chinese recipe. It involves a metal pot with boiling broth in the middle of the table, kept hot by a small cooker underneath. The pot may contain different types of broth separately, with various spices, and goes together with a variety of raw ingredients: meat, fish, greens, noodles and seasonings. Diners are supposed to cook the food the hot broth and then dip it in the seasoning, which is usually sesame oil. and playing mahjong. These are the stories of Chengdu. What I really hope is for graffiti art to develop in my city. To achieve this, it is important to let people know what you are painting. Hence, my idea is to paint their lives. I study many techniques and various painting styles, but I think graffiti is the best way to show my work to the public. I don’t want to paint at home, where no one can see what I’m trying to communicate. By doing it outdoors, everyone can appreciate it. (Ibid.)

At the start of his career, Fan Sack devoted himself to bombing the streets of Chengdu with his tag and experimenting with various forms of writing, from simple tagging-up to the creation of more complex pieces, restyling and renovating the old school patterns. An example of this type of work is a spray-painted piece made in Chengdu during his early career. In it, he depicts his tag SACK in a rather articulate wildstyle and making skilful use of 3D. The letters are completely white and surrounded by a thick black outline that gives them three-dimensionality. The colours are very bright, and the style is purely western; only small details such as tiny lotus flowers or bamboo leaves inside the letters bring up the “Chineseness” of the piece. The central piece with the inscription SACK always comes with the word Yan (eye) written differently near or within the piece. This word has accompanied the artist throughout his career, although acquiring different forms in recent times.

In another work from 2008 (Pic. 26), for instance, Yan is repeated several times, thus confirming its importance for Fan Sack from the very beginning: around the elaborate tag SACK in wildstyle with hints of 3D, the word Yan is repeatedly written with typographic-like lettering11Lettering – The style of the letters, and the pivotal concept of graffiti writing. Writers first and foremost paint letters, which may differ in size and style: block consists of large, square or rectangular letters, usually filled with one colour; soft consists of round, soft, cloud-like shaped letters, usually of one colour within an outline; in bubble style, the letters look like soap bubbles, very precisely coloured and with a wide outline; in wildstyle, the letters are composed of intersecting three-dimensional arrows, which give the idea of movement and confusion. In the case of Chinese graffiti art, since many writers also use characters in their pieces, a new term was coined to indicate the style of the characters: Charactering. in white on an orange background. This is the prelude to the artist’s future iconic tag (an eye inside a sun), employed in all his more recent works (cf. Rupa Fig. 14). In this piece, Fan Sack also inserts two puppets: the first, on the right, is a cartoon-style writer with a spray can in his hand. The can’s jet originates a white cone with the wildstyle tag SACK (the actual piece) on the inside. On the left of the writing is the second puppet, in realistic form: it is a self-portrait of Fan Sack, depicted from behind with a spray can in his hand, busy bringing his work to life. In the bottom right-hand corner, the date of the piece is written in Chinese format, that is, following the year-month-day order (2008-08-11), together with the name of the city of Chengdu in characters (成都), the piece’s only trace of “Chineseness”.

Although Fan Sack has become a famous, internationally renowned artist, combining his street pieces with studio works for exhibitions and galleries, he knows exactly where he comes from and always remembers where he started out. This is why he often returns to Chengdu, to devote himself to street works and promote their diffusion:

I have made graffiti in many areas of the city, such as Jiuyanqiao, known for its many live music events; but one of my absolute favourites is Chengdu’s newest pedestrian street, Kuixinglou. It is very popular among young people, with lots of trendy clubs and typical hot pot restaurants. Kuixinglou is a great place to bring one’s creations to life, also because it is right next to Nu Space, an innovative venue in Chengdu for live performances and film screenings. […] I largely promote hip-hop culture and the spread of graffiti in China. Every time I go back to Chengdu, I like to witness how writing is constantly evolving. As a result, I love taking part in events and festivals, especially those involving young people who make me proud to contribute to the spread of graffiti. (Ibid.)

Recently, the artist participated in the initiative Simple Urban Plus Festival, a music and art festival dedicated to young people and held in Chengdu on 2 and 3 November 2019. The event, which took place in the Chengdu Tianfu Furong Garden, involved young, talented musicians like the new rap generation idol Jackson Wang12Jackson Wang is a Hong Kong rapper, singer, dancer and tv host. He is a member of the Got7 South Korean band, and took part in South Korean reality shows like Roommate. He is also active in China as solo singer and tv host., as well as a contest13Contest (duijue 对决) – Competition or legal battle between breakers, djs, mcs or writers, the most important of which in China is the Wall Lords Graffiti Battle, or simply Wall Lords (Zhanqiang 战墙). for creating street art. Fan Sack participated in the festival with the piece Fu lu shou xi 福禄壽禧 (Pic. 28). The four characters composing the piece and giving it its title are positioned next to each other on individual panels and are to be read from right to left, in the traditional Chinese manner. In China, it was common practice for a building to have its name written in calligraphic style on a sign placed at the main door, to be read from right to left. Such signs can still be found on temples or important public buildings. In this work, Fan Sack drew inspiration from this Chinese custom. For the characters, he was inspired by the folklore trend of traditional Chinese culture. Fu lu shou xi 福禄壽禧 is a widely used auspicious expression meaning “Luck, Longevity, Prosperity and Happiness”. Likewise, the Fu 福 (happiness) character often recurs in popular culture, on the doors of houses as well as in many aspects of everyday life. Fan Sack’s is probably a message addressed to young Chinese people entering urban life and in particular street art, which aims at evoking and giving voice to that very popular culture from which the phrase originates. The piece resembles a work of calligraphy: the strokes set out to reproduce those of a brush on paper, and the style is very similar to kaishu, with accents of the running or semi-cursive style (xingshu) in some of the junctions between the strokes of each character. The large format of the writing recalls that of classical calligraphies (dazi shufa). In contrast to traditional monochrome calligraphy, in which the only colour is the black of the ink on white paper, each character is here arranged within a series of multicoloured concentric circles that constitute the background and give three-dimensionality to the character itself. The shading ranges from bright green and yellow to black and purple, enriching and enlivening the piece.

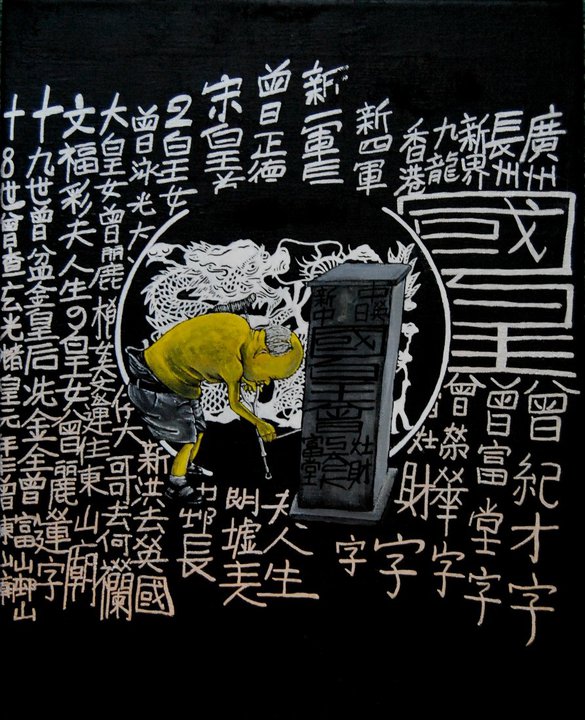

There is another work, created in 2011 in Hong Kong (Pic. 27), in which Fan Sack explicitly refers to Chinese calligraphy, this time drawing on the history of Chinese graffiti and one of the most emblematic figures who attempted to combine calligraphy with graffiti: King of Kowloon. In it, Fan Sack decided to portray the artist Tsang Tsou-choi (Ceng Zaocai), better known as King14King (wangzhe 王 者) – A sort of leader for other writers. Generally, the king is the best skilled writer most respected by everyone. A writer is deemed king only if another king recognises him or her as such. Factors taken into account for this title are the number of pieces made in a city, style, originality, and experience. of Kowloon (1921-2007), famous for his 51 years of activity on the Hong Kong street art scene. The background is filled with calligraphies that explicitly replicate those by Tsang Tsou-choi, following his same style and idea. Meanwhile, in the centre of the work appears the King of Kowloon himself, bent over, writing his calligraphies. In the last years of his life, Tsang Tsou-choi could no longer maintain an upright posture, and yet kept producing his calligraphies. To the right is an electricity counter, also covered in calligraphic symbols imitating the style of the King of Kowloon. The King is surrounded by a circle with a dragon in the background, a traditional Chinese symbol of wisdom, power and luck. Unlike pure graffiti writing, this piece adds figurative elements and was not executed on the streets but painted with acrylic colours on canvas in a studio, in order to be displayed in an exhibition. Although not a graffiti piece in the strict sense, its calligraphic-style characters and the explicit reference to one of the first Chinese writers mark a strong connection with the idea of street art inspiring the work.

Although Fan Sack also makes pieces for the art market, the ultimate goal of his activity is to communicate, to create, everywhere. Not only in his hometown: “I want to share my works with as many people as possible because I believe in karma. For me, when you open up to the world, you necessarily get something back. That is why public places are the most beautiful spaces for creation: the paintings can reach everyone. It is very different to private galleries, which are only visited by those with an interest” (ibid.).

Fan Sack, therefore, prefers to create outdoors, in the streets, although in recent years his art has increasingly shifted from simple writing to figurativism. This classifies him more as a street artist than a graffiti artist. An instance of this is the work Wushen zhi shu 無 神 之 樹 (The Tree of Atheism, Pic. 29), created in 2015 on a wall in the 12th arrondissement of Paris. At the base of the piece is a monkey immersed in the sea, covering its eyes with a leaf. Despite being blindfolded, it marches straight ahead, guided from above by an erudite man, symbolising science and knowledge. Above him is the Lord of Heaven, the symbol of religion and of the creative power of dao, who is in turn surmounted by Picasso, symbolising art. Finally, at the very top is a brain crowned with a vibrant light, symbolising wisdom. The area around the monkey’s eyes is magenta red and the leaf is bright green; these are the only two elements that stand out, catching the eye of the viewer, who is otherwise fully immersed in this ethereal, silent space. The image of the monkey is a signature element appearing in nearly all of Fan Sack’s works. In traditional Chinese culture, this animal embodies intelligence and cunning, whereas in Tibetan tradition it is a bodhisattva, a being who seeks enlightenment by helping other sentient beings through the experience of supreme knowledge. It embodies sensitive consciousness, albeit dominated by inconstancy. With this image, in which Fan Sack superimposes Picasso and the human brain on the Lord of Heaven, the artist pursues an iconographic experimentation reflecting the unbreakable bond between art, science and religion:

For me, art, science and religion are one and the same. As human beings, we want to know who we are, where we come from, why we are here and what the relationship between nature and the universe is. Although art, science and religion are three very different disciplines and each of them has a different application in the world, for me they all have a single point of origin. It is like imagining a tree: it all starts from the same trunk, with firm roots. From this large trunk, then, the three disciplines are born and become three different branches. My works speak of this. (Ibid.)

In this piece the three images of the Lord of Heaven, Picasso, and the brain, emerging from the figure of the monkey (symbolising human nature) and controlled by an astronaut (symbolising exploration), represent the indissoluble bond between the corresponding disciplines of religion, art and science. They all branch out of “one big tree” to provide humans with the essentials of life. Finally, the deep blue background dotted with stars symbolises open space and the universe. This piece is part of the series Enter the oeil, of which the monkey, the colour blue, and the triadic idea of the union of science, art and religion are distinctive features. Another work of this series, painted in acrylic on canvas, was displayed in the renowned exhibition Dalí fait le mur held from 11 September 2014 to 15 March 2015 at the Espace Montmartre in Paris. This exhibition creates a strong parallelism between street art and the surreal world mastered by Salvador Dalí. The 22 street artists15The exhibition displayed the works of 22 artists: Akiza, Artiste Ouvrier, Fred Calmets, Codex Urbanus, Btoy, Hadrien Durand-Baïssas, Jadikan, Jérôme Mesnager, Les King’s Queer, Kool Koor, Kouka, Levalet, Thomas Mainardi, Manser, Nikodem, Nowart, Paella, Pioc PPC, Sack, Speedy Graphito, Valeria Attinelli and Zokatos. involved were given carte blanche to create works that followed the creative wave of the Spanish surrealist artist. Like Dalí, street artists impose no limitations to their inspiration and the materials they employ. They also share Dalí’s artistic means of revealing the world to their audience: provocative, iconoclastic, savage. The paintings of the surrealist genius and the multifaceted creations of the contemporary artists involved were thus shown to the public side by side, in a set-up that drew inspiration from their respective worlds. Starting from street art, the exhibition went straight to the beating heart of surrealism, following the common thread that bonds both styles through a natural proclivity for the unconventional (Hauer 2014).

In Fan Sack’s work on display, Salvador Dalí fulfils the role of Picasso in the previous piece. The artist depicts the body of an astronaut, symbolising science and offering a means of glimpsing the universe, dominated in sequence by a monkey, a Buddha and finally Salvador Dalí. Respectively, they incarnate human nature, religion and surrealist art. Above Dalí’s head stands a heart with an all-seeing eye on the inside, from which coloured concentric circles radiate outwards. This is the “watchful eye”, pointed straight ahead and looking to the future. This is how the artist describes his work:

This is one of my favourite works, where my creation is displayed next to that of the legendary Keith Haring. It’s an authentic thrill. This image is my way of disclosing my vision of religion, nature and science, bringing viewers into my imaginary world and giving them full freedom of interpretation and emotion. (Ibid.)

Although it is not a piece of graffiti, the connection with street art is highlighted by two elements: the work forms part of an exhibition dedicated to street art and attended by internationally renowned street artists; and, as a result of this exhibition, Fan Sack coined the concept of graffuturisme, a new form of graffiti art that looks to the future through the watchful eye he portrayed.

In addition to writing pieces, actual street art, and works on canvas recalling the idea of street art (such as those analysed so far), for years now Fan Sack has also been producing commercial works using the typical tools and media of graffiti (e.g., spray paint on walls), like many of his Chinese and non- Chinese colleagues. An evocative example is the large sleeping Buddha created in 2016 at the Masha Restaurant in Paris, near the Eiffel Tower. In this work, the Buddha’s garment is covered all over by the well-known Louis Vuitton logo, along with a series of spheres that most likely symbolise the terrestrial planets. At Buddha’s feet, a monkey musician is depicted on a trail of clouds, alongside other symbolic elements of human art. The dominant colour is red, with shades of powder pink through to deep purple. Buddha is wearing virtual reality glasses, a symbol of modern technology but also of optical art16Optical art, or opt art, is an abstract art movement that started around the 1960s and further developed in the 1970s., in reference to the teaching of Buddhist scriptures whereby “everything becomes spirit after being possessed by evil forces”:

One of my influences, as is quite common among those considered “extravagant and out of the ordinary”, is optical art from the sixties and seventies. It is so psychedelic. In China, this movement, with its spirit of freedom, is very interesting and extremely stimulating for my generation. Our parents had no idea of what was happening in the western world back then; they knew nothing about it. China was still closed at that time. (Interview, 2019)

In this work, Fan Sack blends the sacred with the profane, religion with business, East with West, art with the art market; and he does so rather provocatively, echoing the modalities of street art.

From graffiti writing to graffuturisme, via street art, and through to more refined experimentations in the field of art on canvas, over the course of his career Fan Sack has increasingly shifted his focus to purely Buddhist works, regardless of the artistic technique employed, depicting representative images of eastern culture. The work collection Rupa (Fig. 14), displayed in 2016 at the J Plus Hotel in Hong Kong, epitomises research and experimentation with art seen as revelation, with the artist explaining how religion, nature and science are not only part of a whole underlying human life, but even become a “universal law” capable of governing the entire world.

Rupa is a Buddhist term which represents reality, existence, nature. Human nature is embodied by a bright red ape-like figure immersed in the tranquillity of the surrounding space. The monkey is the soul of the dao, wrapped in a fiery red aura. On the top left is the all-seeing eye, also known as the “eye of providence”, and on the right is an inscription in the Tibetan alphabet. A human is praying on the lower left, and in front of him, on the right, a scientist is holding an alms bowl. In Buddhism, the bowl symbolises the middle ground between rigour, frugality and attachment to life. It is also indicative of the lifestyle of monks who, every day, live off people’s gifts. These three figures surrounded by a red aura also serve as incarnations of art, science and religion, immersed in an open and charmingly scenic space. Although this work seems to have nothing to do with graffiti art, there is a small detail – which Fan Sack seems unwilling to give up – that reminds us of it: the watchful eye, depicted in the top right-hand corner inside the sun, as a symbol of unity, balance, wisdom, spiritual awareness and, above all, enlightenment. This element is a reference to the YAN tag used in his early graffiti17Graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) – A worldwide social, cultural and artistic phenomenon born in the 1970s in New York ghettos as a spontaneous expression, with no declared intent, of a heterogeneous group of young people belonging to the hip-hop subculture. The etymology of the word graffito derives from the Latin gràphium, or “style of engraving”, which in turn stems from the Greek gràphein (γράφειν, to scratch, to hollow, to draw). The English term “writing”, instead, stands for the act of creating one’s tag in public spaces using spray paint or markers. It entails a study of lettering, namely the style of the characters that make up both simple tags and pieces. In China, the term “graffiti” does not only refer to the writing of letters or characters as in writing, and thus graffiti is also called tuya yishu 涂 鸦 艺 术 (lit. graffiti art), implying a wide range of artistic expressions on public soil (making it much closer to street art). Another term used is tuya huihua 涂 鸦 绘 画 (lit. graffiti painting), which refers to graffiti containing puppets.; as Fan Sack’s art evolves, the tag evolves with him. This figurative “eye” becomes the artist’s new tag and can be found in a great deal of his recent works as a sort of vigilant peephole that gives a new insight into the world. In the last few years, this eye has become the protagonist of some of his street art pieces, where the eyeball has been turned into a huge circle containing figurative references to Chinese tradition, as a means of reflecting upon the present.

Fan Sack is basically an ever-changing experimental artist. As he explains:

I’m still testing and experimenting. I believe it’s important for viewers to give their own interpretation of my works; I don’t want to limit their perception. The advertising designs I create don’t have a single, straightforward, identifiable message. I want to give people space to think, to interpret. People forget about advertisements in the blink of an eye. I would rather that those who see one of my works for the first time carry it with them, in their memory, without an immediate response. I would like them to analyse it afterwards, to form their own thought. With no interaction between me and the public, my work is only halfway valid. (Boraccino, 2019)

The dream of this Chinese artist based in Paris is to spread his art everywhere:

Where do I come from? China, because I grew up and lived there until I was 20. Then, ten years ago, I planted my roots elsewhere, in Europe. How can I express both my identities? I believe artworks are part of the artist’s soul and worldview. I want to do everything, experiment with everything; and, above all, I don’t want to set limits. I am interested in all cultures, populations, social classes. I was born in China; but even before being Chinese, I am a human being. I moved to Paris in order to grow and gain experience. We only live once. We must do what we want and do it well. One day everything will be gone, for all of us. This is why I’d rather regret something I have done, instead of doing nothing. I chose adventure and, indeed, life goes on. (Ibid.)

Fan Sack is an artist tout court who, just like many other Chinese writers, started off bombing Chengdu’s streets with his tag and experimenting with various forms of graffiti, until he found himself creating ever more elaborate pieces that transcend simple street art and have even made it into art galleries.

However, Fan Sack’s artistic evolution still remains anchored to his origins: with references to calligraphy, he emulates those who have “marked” the streets before him, like the King of Kowloon, the iconic forerunner of writing; he participates in events that stimulate young writers to promote street art (like the Simple Urban Plus Festival); he uses spray cans for indoor and business-focused artworks; he adds sacred symbols of Buddhist art in his works, and coined the term graffiturisme to indicate an new, extravagant and unique art. These are all clear indicators of his constant focus on graffiti art and Chinese culture. In short, Fan Sack may be described as a complex, multifaceted artist, and perhaps one of the few, among his many Chinese colleagues who started out like him, to have embarked on a fruitful, ever-evolving career with an international scope.

Fan Sack concludes this excursus on Chinese graffiti art, an unstoppable phenomenon posing as a vehicle for new forms of expression. We hope that our research has opened up a window onto the largely unexplored aspects of modern-day China, providing a deeper insight into its rich and profound culture, which invariably manages to convey its everlasting charm.