IV. SHANGHAI, A COSMOPOLITAN AND INTERCULTURAL TREND

Marta R. Bisceglia

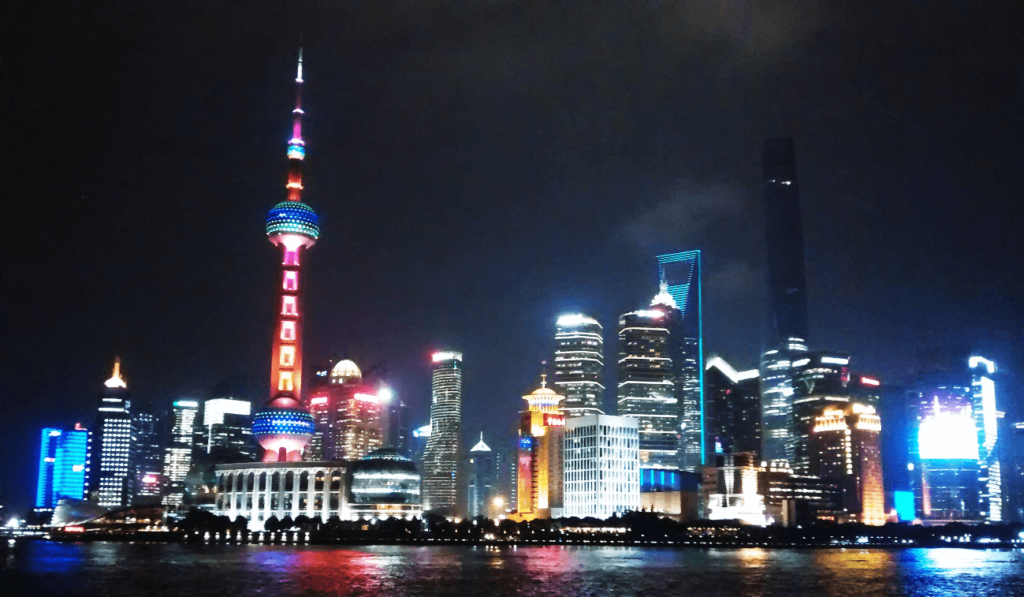

Shanghai is the most populous urban area in China and the most populous city proper in the entire world. Considered the economic capital of the country, it is one of the world’s preeminent financial, commercial, technological and communications centres following its development in the last two decades. Known as the “Oriental Pearl” due to the sparkling and iconic Oriental Pearl Tower – the television tower rising up from the skyline of the financial district of Pudong – and as the “Paris of the East” due to the European-style architecture of the French Concession district and the Bund boulevard (Agliardi, Gennari 2018), Shanghai is a city of contradictions, where East and West, past and future coexist in perfect harmony.

It covers an area of 6,340.5 km2 and has about 27 million inhabitants (Tonarelli 2017). Its official language is standard Chinese, or putonghua 普 通 话, but many residents, especially from the Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces, speak a variant of the Wu language, the second most spoken dialect in China after Mandarin. In Chinese, Shanghai 上海 literally means “on the sea”, in reference to the city’s geographical location, overlooking the east coast of the East China Sea and stretching along the banks of the Huangpu River at the delta of the Yangtze River. This ideal location makes it one of the busiest commercial maritime ports in the world. The Huangpu River divides the city into two macro-areas, namely Pudong 浦东 and Puxi 浦西, whose names reflect their geographical locations: on the east bank of the river lies the Pudong area, which is home to the city’s financial district, while on the west side lies Puxi, the old town. Pudong is commonly regarded as the Shanghai of the future and Puxi as the Shanghai of the past (China in Italy 2019).

Shanghai is modern, innovative, with a slight European feel but rooted in history. Although partly outclassed by the advancing future, this history coexists peacefully with the skyscrapers that reflect their lights onto the Chinese Sea (Agliardi, Gennari 2018). The history of Shanghai, however, has not always been so bright. On the contrary, it was often tinged with gloomy grey and blood-red shades. In 1075, during the Song dynasty (960- 1279), Shanghai acquired its current name and was elevated from the status of village to that of merchant city. In 1554, the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) erected a 5 km long and 10 m high wall around the old city centre to protect it from the attacks of Japanese pirates. Next, with the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), Shanghai started to see the first important results of its port activities. This stemmed from two major political changes: the first occurred in 1684, when the Kangxi Emperor (1661-1722) lifted the existing ban on ocean ship sailing, and the second in 1732, after the Yongzheng Emperor (1678-1735) moved the customs office for the Jiangsu Province from the capital of the prefecture Songjiang to Shanghai, giving the city exclusive control over foreign trade customs operations. As a result, the city’s fate changed radically, with Shanghai becoming the primary gateway to China’s maritime trade with the West, thus catalysing the attention of the leading world powers.

During the first Opium War (1839-1842), the city of Shanghai was occupied by the British army. The war ended in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking, which opened up five ports to international trade, including Shanghai. In the second half of the 19th century, Shanghai was the battleground of a civil war known as the Taiping Rebellion, during which the city was attacked and destroyed. In the early 1900s, it became the destination of migrants from all continents, especially Russians and Jews fleeing the newly established Soviet Union. In 1936, Shanghai was the sixth biggest harbour in the world and the major financial, commercial and manufacturing centre in the country. In May 1949, the People’s Liberation Army seized control of the city. Even after the Communist regime came to power, Shanghai remained China’s main industrial and research centre and underwent significant changes throughout the following decade, including the relocation of most foreign businesses to Hong Kong. However, in 1991 Shanghai began undertaking new economic reforms that significantly increased its development to a degree still visible to this day (China in Italy 2019). The cosmopolitan nature of Shanghai began to take shape in the mid-19th century, with treaties that granted foreigners the possibility of settling and operating in China. The Chinese and western culture began to merge inextricably, forming a unique mélange that still persists. Today, Shanghai is one of the largest cities in the world and constantly undergoes fast-paced transformations: even if the traditional urban and architectural structure is in danger of disappearing, the one thing that does not change – and in fact, reinvents itself – is the city’s cosmopolitan nature, a one-of-a-kind experiment in the name of “contamination”, which is the key word for understanding its essence (Salviati 2004). The eclecticism of Shanghai’s urban landscape is also reflected in the mixture of tradition and modernity, as well as in the extravagant stylistic fusion between West and East: on one side, the futuristic skyscrapers of Pudong, on the other, the ancient lilong or longtang alleys (similar to Beijing’s hutongs) and the shikumen-style residences (traditional dwellings, similar to European terraced houses). Another extravagant feature of the city is the presence of Buddhist temples, such as the Jing’an, Longhua and Jade Buddha temples, nestled among ultra-modern buildings.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the remarkable contrast between the stunning, everlasting Yuyuan Garden and the bustling, overcrowded Nanjing Road, the famous shopping street glowing with neon signs, which runs from the Bund to People’s Square.

In this square, once the site of the hippodrome of the English Concession, stands another newly erected building whose function best symbolises the link between old and new: the Shanghai Museum, one of China’s most important in terms of the number and quality of its exhibits. Here, over 120,000 artefacts span the entire chronology of the development of Chinese civilisation, from the Neolithic age to the 20th century. Founded in 1952, the museum was reopened to the public on 12 October 1996 in a new venue designed by architect Xing Tonghe, whose idea for the shape of the building was to have it resemble an ancient bronze vessel (Salviati 2004).

Moganshan Road, the Shanghai hall of fame

The city of Shanghai showcases a continuous series of events, exhibitions and vernissages, which give the Chinese metropolis a stimulating and constantly expanding cultural fervour. Creative spaces like the M97 Gallery, Rockbund Art Museum, Art Labor Gallery, Power Station of Art, MoCA, Shanghai Gallery of Art, Oriental Vista Gallery and Leo Xu Projects stand as a demonstration of this. The heart of the contemporary art scene is above all the M50, a large community of urban artists who have long occupied an abandoned industrial district near the Suzhou River and transformed it into a complex of galleries, studios, workshops, art spaces, bars and restaurants. This is an inspiring place where artists like Xue Song have moved their studios, giving birth to a neighbourhood where people have been living and making art since 2000 (Bini 2016). Every metropolis worth its salt has a so- called artistic district reflecting the city’s most inspiring contemporary art scene: Greenwich Village in downtown New York, 798 in Beijing, Pigneto in Rome, and so on. With Moganshan Road, Shanghai holds its ground in this regard. An excessive amount of so-called “Chinese-style art villages” in Shanghai had resulted in a decline in genuine interest in art itself: some such places were merely glorified gift shops, displaying art alongside neo- pop merchandise and brightly coloured designs of doubtful aesthetic and artistic value. However, Moganshan Road, commonly referred to as the M50, remains the hub of metropolitan art life. New museums and galleries do not disdain these outwardly pseudo-degraded post-socialist corners of the city with a somewhat hipster charm. The M50 (where 50 is the house number) hosts a collection of fascinating new and old realities. To name a few: the Vanguard Gallery, which has been exhibiting up-and-coming artists in its contemporary white-cube environment since 2004; the ShanghART Gallery, one of the largest and liveliest spaces, with an extensive bookshop that is well worth a visit, which has been home to some of the most exciting exhibitions of recent years; and the artistic collective Liu Dao, founded by Frenchman Thomas Charvériat in 2006, situated at the Island6 Gallery (one of the many galleries of the collective). Liu Dao is an artistic group that creates impressive artistic-technological works now featuring in museums and collections all over the world. The small square at the entrance also serves as a background to the various artistic initiatives and parties that animate this space every month. This urban area is worth exploring: the old industrial buildings create an intricate itinerary, where visitors can roam freely and stumble on exhibitions of stimulating emerging artists. If you are ever passing through Shanghai, even for a few days, it is definitely worth taking the time to visit (Rubini 2016).

The history of the M50 District follows that of Beijing 798 Art District. Both were established in abandoned industrial areas, converted and revived by artists in search of affordable spaces for their ateliers. Over time, these workshops have fascinated fans and reached international fame, turning into galleries and must-see destinations for art-loving tourists. Interestingly, the buildings at Moganshan Road 50 are still the property of Shangtex, a state-run textile group that also owns the Chunming Slub Mill plant, formerly located at Moganshan Road 50. The history of this district is also significant in relation to the changes experienced by Chinese society, with manufacturing being replaced by high-level artistic production. This shift in artistic taste was accompanied by a rise in the bourgeoisie, whose domestic and international financial investments took over a sector based on cheap labour. Art and business in Shanghai go hand in hand (Piotr 2015).

Before 2018, the most colourful and vivid hall of fame1Hall of fame (tuya qiang 涂 鸦 墙) – A space where graffiti writing is (more or less) legal. Halls of fame are mainly popular with writers who aim to create artistic, sophisticated pieces, favouring quality over quantity and constantly searching for original styles. in the city – indeed, the only one – stood 200m to the right of the M50: the glorious wall of Moganshan lu 莫干山路 (Moganshan Road, Fig. 12).

For over a decade, the dusty lane running along the southern bank of the Suzhou Creek was the center of Shanghai’s street art scene, famed for its long, serpentine “graffiti wall.” But last year, the wall finally came down, and with it went the city’s only remaining haven for graffiti writers. (Davis 2019)

The aim was to make way for the Heatherwick Studio’s majestic 1000 Trees Building project, a futuristic plant-clad building complex whose first section opened in late 2021. The M50 district thus became crowded with massive housing projects and luxury residences that increased its real estate value. Consequently, it was constantly threatened with the risk of dismantling due to rapid urban change and gentrification despite its growing artistic prominence (Bruce 2010), up until the dismantling became a sad reality accentuating the precariousness of graffiti art, a fact which is well known among writers2Writer (tuyazhe 涂鸦者 / penzi 喷子 / tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家 / xieziren 写字人) – An artist who executes graffiti mainly based on lettering.. Before venturing into the story of Shanghai’s and China’s most celebrated hall of fame from 2006 to 2018, we should start with the present day, or rather with 2019, the year after the wall’s removal.

From 9 to 15 November 2019, through an Urban Art United (UAU) initiative, more than thirty artists filled a plastic slatted fence along Moganshan Road with their graffiti. The festival 1000 Trees Symbiosis Exhibition collaborated with SUSAS 2019, sponsored by the 1000 Trees Building’s real estate promoters and the Shanghai Urban Space Art Season (SUSAS), hosted most of the artists who made the history of the wall and some great names of the world’s urban art stage, including VHILS3The Portuguese artist Alexandre Farto, aka Vhils, approached graffiti in 2000 and is now a world-famous street artist., DALeast4DaLeast was born in China in 1984 and started his artistic career as graffiti writer, joining the JEJ crew in Wuhan with the tag DAL. He currently lives and works in South Africa and is a world-renowned street artist. His nickname DALeast comes from the combination of “DA” and “east” (eastern). and Mode25Mode2 is a famous Mauritian artist who has been active since the 1980s.. “For the organizers, the event was a chance to add a splash of color and hype to the 1,000 Trees complex – a futuristic, flora-covered building set to open in 2020. But for the artists, the gathering represented something else entirely: a final chance to paint on their beloved street, Moganshan Road” (Davis 2019). The festival lasted about one week, but the graffiti remained for about six months, until the construction was completed; the greatest artists’ works at the top of the building, instead, are permanent.

The event also included workshops for the district residents, who had the opportunity to decorate the slats together with graffiti artists. The creations ranged from traditional graffiti lettering to murals of dragons, flowers, and a zombified Michael Jackson. “One piece, however, did not survive long. Within a week, a shadowy image of a woman wearing a gas mask while covering her eye with two fingers to make a loaded gun gesture, with “Moganshan 2006-2019” written in the corner, was covered over” (ibid.). Jin Ye 金 烨 (who over the years went by the names Hur(r)i, Read and recently Hali)6Many artists use more than one tag: Jin Ye was formerly known as Huri or Read, while today his tag is Hali (interview by M. R. Bisceglia in Moganshan Road, 11 September 2014)., a member of the Oops crew7Crew (tuandui 团队) – In hip hop culture, a circle of people collaborating on artistic or cultural projects, e.g., a group of writers or dancers. In graffiti writing, a crew is an organised group of writers who paint together to create pieces. They are usually friends, meaning they share mutual esteem and respect. A writer may belong to more than one crew over time, or even at the same time. The name of a crew is normally an acronym of two or three letters, possibly having multiple meanings. Like tags, crews’ names are often written on the side of the piece, or they form the very core of the piece, with the name of the crew members dotted all around. and active on Moganshan Road since 2006, thinks that the removal was a laughably petty act that encapsulated how the area has become commercialized and controlled, and stated: “for so many years, no one cared what you drew there, then suddenly they do this event and are restricting people from drawing things. Moganshan Road is no longer the real Moganshan Road: It’s become plastic. They want graffiti, but also don’t want it” (ibid.).

Dezio, a French graffiti writer who has been writing since 1994 and who co-founded Urban Art United (UAU) in 2017, began making graffiti at the wall in 2006. He witnessed its birth, saw it thrive and become one of the most famous in the entire country, and then watched it fall. During the event he painted three sections of the fence, two of them with large format flowers from the Suzhou River (Symbiosis, Pic. 19). In the first section, the flowers were red and yellow on an orange background. Their shading created three-dimensionality, and, despite the use of bubble style8Bubble style (paopaozi fengge 泡泡字風格) – Rounded, old school style lettering, still extensively used in throw-ups due to its quick execution. The letters recall soap bubbles and are painted with great precision. The outline is usually thick, with a white inline to enhance the depth of the lettering. Phase 2 originally created this style., the petals looked like they were moving. In the second section, the tone was significantly colder: the two flowers in the foreground were pale orange and yellow, while those on the background, in “bombed” style, were pink and purple. The stems and leaves were dark purple, and their square shape was reminiscent of the thin blades of a fan, perhaps to express the idea of a breath of fresh air. The last section, which most epitomised his art, displayed a yellow background with a red oblique brushstroke on the left and a pink horizontal one and a blue bubble style one above, symbolising the course of the Suzhou River through the city. Finally, a thin black line stood as a hint of his tag9Tag (qianming tuya 签 名 涂 鸦) – The pseudonym, stage name, or code name that every graffiti artist, mc and breaker uses to distinguish themselves, to stand out and highlight their presence in the city. Being the most basic form of graffiti, created with spray cans or markers, the tag is the backbone of the writing phenomenon. The evolution of the tag represents the personal style of its author. All pieces, even the largest, most colourful and elaborate ones, remain, in essence, signatures. The activity of marking a surface with a tag is called tagging-up, while tag bombing is the reproduction of one’s tag on a large scale in a certain area of the city. Tags can also be representative of entire groups. Different writers or mcs who join together can decide to use one comprehensive tag, as a symbol of the group (see Crew)., almost like a ghostly presence. This last feature sums up the nature of graffiti artists, which is to be there without being there: it is far easier to see a piece than the artist at work.

The Russian artist Feat – a habitué at the wall – painted a 9 m long piece during the festival, mixing Chinese and western elements, including a traditional fishing boat and a Roman bust (Davis 2019; Pinheiro 2019). The presence of such a multitude of international artists in Shanghai manifests its cross-cultural and transnational nature: foreigners making use of Chinese elements and Chinese writers employing western cornerstones in their works.

In its heyday, Moganshan Road’s long wall drew tourists, introduced locals to street art, and provided a safe stomping ground for budding graffiti artists. But its destruction and an increasingly rigid atmosphere in Shanghai are resulting in a declining street art scene, with artists struggling to find places to paint. (Davis 2016)

To understand how things got to this point, we have to go back in time to 2006: “The area proved to be the perfect location for graffiti: a post- industrial dead zone on the border of three separate districts – Zhabei, Jing’an and Putuo – that was rarely frequented by police. Even better, one side of the street was lined by a huge, bare concrete wall, built to fence off some wasteland awaiting development” (ibid.). The M50 district provided further protection, since the residents of Moganshan Road assumed that the tags were somehow associated with the art district on the other side of the street. To be fair, the M50 probably played a much more important role in protecting the wall. About this, Dezio recalls that police officers often threatening to arrest him in the early days. Then, one day, a director from M50 passed by while him and a few other artists were painting and told them how much he appreciated their work. Handing over his business card, the director told the artists to show it to the police next time they hassled them. They did it, and the graffiti writers were never prevented from painting at Moganshan Road ever again, “the wall got ‘legalized’ at that point” (ibid.).

In the following years, Moganshan Road saw its golden age, attracting many tourists and artists of great fame, such as the German writer Cantwo or the British Roid. In this regard, Jin Ye recalls his surprise at discovering that art schools were bussing their students to Shanghai to study his work: “Graffiti went from being this thing that us kids were playing around with, to something popular that people would go see and discuss: it suddenly went up a level” (ibid.).

The wall became evermore colorful as artists from a variety of backgrounds tried their hand at painting or “wheat pasting” – sticking up paper wall art using a wheat flour and water solution – on its concrete canvas. Brands including JD.com, Nike, and even the video game League of Legends also started flocking there, doing fashion shoots, filming music videos, and creating their own art. Dezio is particularly moved when he recalls the reactions of the neighbourhood’s inhabitants at that time: children would sit next to him and watch him paint, and teenage girls inspired by his work would try graffiti themselves; but what struck them the most was that he was creating art for free and even paid for his own spray paint!

And yet, from 2015 onwards, the graffiti art scene in Shanghai began to dissolve, even though the wall was still standing. Increasing control and fewer spots available meant that artists began moving to other cities or turned to more lucrative activities like graphic design or tattoos. According to Dezio, there is no large place left in the city to make graffiti, because there is no place like Moganshan Road, and therefore the art of graffiti has been severely jeopardised. Even the M50 artists and gallery owners are worried that great commercial developments will continue to inflate the already high rental costs and make the neighbourhood a place for shoppers and tourists rather than real art collectors, thus damaging its bohemian atmosphere. Jin Ye claims to have mixed feelings about the end of Moganshan Road. He was devastated when he first heard the wall was slated to come down, but over the years he became resigned to its destruction. Jin’s art studio is in distant Songjiang District – a one-hour drive from downtown – where he’s found new walls on which he can paint. Though fewer people will see these murals in person, thanks to social media platforms like Instagram, his street art reaches a greater audience than ever. “If we’re just talking about the reach of graffiti art, right now it doesn’t matter too much that we don’t have Moganshan Road,” says Jin. “If you have a good hashtag, a good social network or marketing thing, you can broadcast much farther” (ibid.).

It is therefore common practice among the “new school” of Chinese graffiti artists to be more present on the internet than on city walls. Spreading tags everywhere, with the risk of being sued or put in prison, is no longer a requisite, nor is favouring quantity at the expense of form: graffiti artists now prefer one meticulously executed piece that can be immediately photographed and posted on social media. Acknowledging the rapid evolution of technology and media, many street artists around the world have conformed to this new philosophy, but in so doing, the very essence of graffiti writing10Graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) – A worldwide social, cultural and artistic phenomenon born in the 1970s in New York ghettos as a spontaneous expression, with no declared intent, of a heterogeneous group of young people belonging to the hip-hop subculture. The etymology of the word graffito derives from the Latin gràphium, or “style of engraving”, which in turn stems from the Greek gràphein (γράφειν, to scratch, to hollow, to draw). The English term “writing”, instead, stands for the act of creating one’s tag in public spaces using spray paint or markers. It entails a study of lettering, namely the style of the characters that make up both simple tags and pieces. In China, the term “graffiti” does not only refer to the writing of letters or characters as in writing, and thus graffiti is also called tuya yishu 涂 鸦 艺 术 (lit. graffiti art), implying a wide range of artistic expressions on public soil (making it much closer to street art). Another term used is tuya huihua 涂 鸦 绘 画 (lit. graffiti painting), which refers to graffiti containing puppets. – throwing your tag wherever and whenever you can to mark your presence in the city – has been lost. This is the first of three factors that have led to the decline of graffiti in Shanghai over the years. The second determiner is linked to control and censorship, as is often the case with art.

As Dezio points out:

The city’s artists also have to deal with an increasingly controlling environment. When new galleries open, the venues often want graffiti writers to come work their magic – but only if they first get approval for their designs. When French artist Julien Malland, also known as Seth, painted a series of murals of an innocent child playing on some Shanghai ruins in 2017, the dash of art was initially welcomed. But after a viral article interpreted the paintings in a political light, many were painted over. Donghua University had a free wall for several years, but it was also painted over in white earlier this year. (Ibid.)

The third factor concerns a growing commercial offering: local authorities, property developers and entrepreneurs commissioning projects to street artists with the aim of embellishing the urban landscape. Even Dezio, who would never have worked on commission in the past so as not to betray the free spirit of graffiti, softened his stance and started accepting projects for profit, provided he was free to maintain his own personal style. Jin, meanwhile, says that the rise of hip-hop11Hip-hop (xiha 嘻哈) – A cultural movement that emerged predominantly in the Afro-American and Latino communities of the Bronx in New York, in the late 1970s. The four main aspects or elements of hip-hop culture are speech, music, movement and sign: MCing (shuochang 说 唱), or rap music introduced by Afro- Americans (MC is the acronym of Master of Ceremony); Djing (dadie 打 碟), introduced by Jamaicans; graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) and breakdance (diban wu 地板舞 o pili wu 霹雳舞), introduced by Puerto Ricans. culture in China is providing him with ample business opportunities, due to the high demand for graffiti-style designs. He received a commission from the NBA to create urban-looking T-shirt designs featuring U.S. star Stephen Curry. Lastly, Jin still feels grateful to Moganshan Road: because of it, the former engineering student found his passion and made a career in art. From graffiti, he has moved on to tattoos, graphic design, and canvas painting. “From the moment I first encountered graffiti, my life was never the same again,” says Jin (ibid.).

And so we have reached the end of the history of the wall. But how did it all start? How and when did graffiti arrive in Shanghai? In an interview, Dezio explained that graffiti came to China from Hong Kong. In 1998 it arrived in Canton and spread to the big cities within a few years. The Shanghai art scene remains relatively new: it is not a widespread phenomenon, but rather an “underground thing” that people don’t know much about except what they see in American rap videos. There is no bombing12Bombing (zhajie 炸 街 / beng 崩) – Filling walls and trains with illegal graffiti, typically throw-ups, tags, stencils or simple lettering pieces that can be executed quickly. This is the favourite practice of writers whose primary aim is quality, and who cover the city with their tag to attain the fame of king., because everything is cleaned in a matter of days, if not hours. In a big city with skyscrapers everywhere, it’s arduous to write your name and stand out. What I hate is the constant buff13Buff or buffing system (qinchu tuya 书法涂鸦) – The removal of illegal graffiti, but also the act of writers when they cover other artists’ tags with their own, or with any other sign. and the stereotyped idea of graffiti being “a hip-hop cool thing” (Sanada, Hassan 2010).

To be more precise, graffiti spread to Shanghai around 2005-2007. One of the first and foremost crews to paint in the city was P.E.N., founded in 2005 by Mr. Lan and Sail, both natives of Changsha in the Hunan Province (Valjakka 2016). The crew’s name is both the acronym for Paint Every Night and a reference to the Chinese character pen 喷 (to spray). Zhang Lan, Mr. Lan’s given name, was one of the first active writers in Shanghai. He is a multidisciplinary artist who ranges from graffiti writing to design, from sticker14Sticker art (tiezhi 贴纸) – A form of tagging through computer-printed stickers that may contain only the writer’s signature and/or logo or be more elaborate, including small fonts and decorations. Sticker art is quick to execute, cheap, and easy to disseminate, and is considered a sub-category of graffiti art, although some writers believe that this type of art is only for those who are afraid of using markers or spray cans. to tattoo art (Bruce 2010). Talking about tattoos, he has stated that his “canvas” is the skin, and that fine graffiti has a lot in common with first-rate tattoos – both have been and will always be his greatest aspiration in life (Shapiro 2009).

Among the forerunners of graffiti art in Shanghai we must include Alex Chou (Mr. Zhou). It is actually unclear whether he should in fact be given credit for the spread of graffiti in Shanghai, since he probably founded the Reload crew in 2004, one year before the P.E.N. crew was established. He too started making illegal graffiti in abandoned or soon-to-be demolished areas, and later agreed to work on commission for companies like Nike, Converse and Calvin Klein. He lived in Germany for years, where he came into contact with the art of graffiti. Once back to China, he left his job to practise what he had learned abroad. For him, graffiti is purely western in culture and tradition, and therefore he does not include traditional Chinese elements or characters in his works.

Another noteworthy artist is Popil, one of the few female representatives of the movement in China. She started her activity in 2009 using nothing but brushes, and currently focuses primarily on commissioned projects. Born in 1985, Popil is a cross-media illustrator from Canton. Like many other Chinese artists, her skills range from drawing and painting to digital design, 3D mapping, and more besides. Her eclectic style includes a multitude of techniques. In her works she uses vivid colours and creates captivating puppets, including her iconic letter girl (in her lettering pieces, she always inserts the figure of a girl next to or in between the letters). Her mastery of these techniques has influenced other artists, making her a point of reference in the world of illustration. In an interview, she states that in her works she simply writes her name – Popil – together with a few Chinese elements that are representative of herself and her style: a young woman, a cat, clouds – simple and amusing things, like her. According to Popil, graffiti is not a political act but a means of personal expression; her art has to do only with her individuality, her loved ones and her expressiveness. Making graffiti is a way of asserting some kind of ownership of the public space, turning it into a subjective space of representation. She also talks about the difference between tag and piece, defining the former as a mere mark of one’s presence and the latter as a more elaborate and demanding artistic effort that expresses something, rather than defining it (Bruce 2010).

The Oops crew, between futurism and tradition

One of the most influential crews in Shanghai, and the one that best summarised the concept of contamination, is the Oops crew. The OOPS crew was and still is the most famous and respected crew in Shanghai. It embodies the cosmopolitan and transcultural trend of the city in which it was born, combining the Western graffiti art movement with many aspects of Chinese culture. About the crew, Dezio states: “This is one of the preeminent active crews in the city. It concentrates its activity at Moganshan Road and Rucker Park15Rucker Park is a skate park in the Yangpu district, north-east of Shanghai., but you can occasionally find their tags and throw-ups16Throw-up (kuaisu tuya 快速涂鸦 / outu 呕吐) – The first evolution of the tag; a stylised drawing of one’s signature, quickly executed but on a large scale, with few colours that are usually sprayed roughly, even without fill-in. The throw-up is an art of its own: the style is immediate, often very simple and “rubbery”, yet never banal. It only consists of an outline with a monochrome fill-in, but the term can sometimes also indicate any kind of bubble style, thus not necessarily monochrome. This technique is scorned because it is deemed unesthetic, but achieving a good throw-up, quickly and with a precise outline, is no easy task. The throw-up is also known as a flop. Throw-ups can be from one or two letters to a whole word or a whole roll call of names. Often times throw-ups incorporate an exclamation mark after the word or letter. in the rest of the city as well” (Dezio in Sanada, Hassan 2010).

Founded in 2007, the Oops had four official members17In her e-mail interview with M. R. Bisceglia on 15 October 2017, Tin.G affirms none of them stopped their painting activity, but getting together became hard due to their respective schedules, therefore the crew temporarily split up.: Jin Ye (a.k.a. Huri, Read or Hali), already introduced in the previous pages, Reign (or Lame), Snow, and Tin.G (the only female writer of the crew, who will be discussed later on in the chapter). The birth of the Oops crew again demonstrates the importance of the Internet for Chinese writers, as the four components met through a blog and not directly on the streets.

We met on the Internet in a graffiti bbs forum where everyone could share pictures of their work and comment on each other’s. We began sharing photos of our pieces and talking about the passion we shared, and we quickly became great friends ‒ says Tin.G. (Interview, 2017)

The crew has since welcomed other members, including Moon, Aekone (a.k.a. Aek), Redim, Kite, and two European artists, Diase (Italian) and Storm (French), highlighting how there are many foreign writers operating in China who actively collaborate with Chinese crews and writers, contaminating both themselves and each other. The crew combines the western graffiti art movement with the Chinese artistic and cultural tradition, using characters, calligraphy and ancient Chinese symbols, and represents the transcultural and transnational trends in Shanghai (Valjakka 2016, 363). When asked why so many different writers gathered to form a crew, Tin.G responded: “We paint together because we share the same passion, and if we paint together our graffiti will be way bigger and more powerful. Even when we sign one of our own pieces with the name of the crew, we are immediately recognised and respected” (interview, 2017). Forming a crew, therefore, means combining multiple tags to create a much larger one and thus gain greater visibility, not only as a group, but as individual artists as well. The crew’s name Oops refers to the classic onomatopoeic sound uttered when people realise they have done something wrong or incorrect, a subtle interjection the members found funny and adopted as their official designation.

In terms of style, the Oops crew’s pieces refer to the Euro-American tradition, using, specifically, wildstyle with 3D effects, often enriched by a background or figurative elements from the Chinese painting tradition. Their lettering18Lettering – The style of the letters, and the pivotal concept of graffiti writing. Writers first and foremost paint letters, which may differ in size and style: block consists of large, square or rectangular letters, usually filled with one colour; soft consists of round, soft, cloud-like shaped letters, usually of one colour within an outline; in bubble style, the letters look like soap bubbles, very precisely coloured and with a wide outline; in wildstyle, the letters are composed of intersecting three-dimensional arrows, which give the idea of movement and confusion. In the case of Chinese graffiti art, since many writers also use characters in their pieces, a new term was coined to indicate the style of the characters: Charactering. and charactering19Charactering – Term we have coined to designate the style of characters in writing pieces (see Lettering), or the use of Chinese characters in graffiti. draw inspiration from the new school20New school (xinxuexiao 新学校) – As opposed to old school, this term refers to the generation of writers that appeared after the 1980s. In China, it is also used to designate a particular style of lettering that aims to modernise the old school styles. (in China this term also refers to a particular writing style, which aims to modernise those of the so-called old school) and employ the three-dimensional wildstyle21Wildstyle (kuangye fengge 狂野风格) – A complex composition of letters assembled to give a unique shape and dynamic to the piece. In this style, the letters are distorted and superimposed, and sometimes enriched with three- dimensional arrows, tribals, pikes, puppets and other decorative elements that give an idea of movement and confusion. This style can be straight or soft: the first is symmetrical, and the arrows forming the letters draw sharp angles; the second is asymmetrical, and the angles are replaced by curved arrows with rounded points. To increase the perception of depth, in addition to inserting junctions between characters, the entire word structure can be turned into a three-dimensional element. This complicated construction of interlocking letters is considered one of the hardest styles to master and the lettering of the pieces done in wildstyle is often completely undecipherable to non-writers., often enriched with backgrounds and figurative elements.

Within the Oops crew, Jin Ye is regarded as the leader, as well as an expert and prolific author of the 3D wildstyle: “Letters are the soul of the wall, and for me there is no difference between Latin letters and Chinese characters. ‘Graffiti’ is an art that belongs exclusively to the street, not to galleries or institutions, although sometimes it is necessary to work on commission to earn a living” (interview, 2014). His first tag, Hur(r)i, is a diminutive of his favourite film The Hurricane (1999), based on the life of the boxer Rubin Carter. Jin Ye approached the world of graffiti at the age of twenty, watching videos of other writers on YouTube. He never joined the hip-hop culture, as he believed that listening to rap music is not a prerequisite for being a writer. He preferred to paint undisturbed in Moganshan Road, searching for an ever more original style, rather than bombing, which is why he used to do sketches22Sketch (shougao 手 稿) – The draft of the piece. Usually, every writer has a sketchbook in which they practice before painting on walls. and drafts of his pieces before painting them on walls. Jin Ye was part of three different crews: the Oops, the CLW with Dezio, Nine, Fluke and Storm, and the BMC with Mels. The acronym CLW has several meanings: China’s Least Wanted, Colouring Local Walls, and Can’t Let’m Win, while BCM’s acronym means Beast Mode Crew. As we are about to see in the section dedicated to Tin.G, a writer may belong to more than one crew over time, and even at the same time. Within the landscape of Chinese graffiti art, Jin Ye’s experience, his inimitable style, and the endless number of pieces he painted in the city make him an undisputed king23King (wangzhe 王 者) – A sort of leader for other writers. Generally, the king is the best skilled writer most respected by everyone. A writer is deemed king only if another king recognises him or her as such. Factors taken into account for this title are the number of pieces made in a city, style, originality, and experience. and a guide for all the other writers on the Shanghai scene.

Shanghai jianqiang: Shanghai be strong

Among the numerous artworks of the OOPS crew, Shanghai jianqiang上 海 坚 强 (Shanghai be strong, Pic. 18) is one of the best examples of “contamination” between the Western graffiti art movement and the Chinese artistic and cultural tradition. It was painted in memory of the victims of the 2010 fire that destroyed an entire building near Jiaozhou Road in Shanghai, taking the lives of about fifty people (Shi, Wu 2010). Given the fleeting nature of graffiti, which can be documented only through photography, this piece once located on the Moganshan Road hall of fame, no longer exists. Part of the charm of this art form is linked precisely to its transience – the life of pieces on the street depends on institutions, private individuals, or other writers as in the case of halls of fame. Visiting Moganshan Road multiple times in 2014, one could see that many graffiti pieces were regularly replaced, even in the space of a few days24It can be proven by another clue: it is common practice for graffiti writers to add the year in which the piece was painted. Most of the graffiti photographed by M. R. Bisceglia were dated 2014..

Shanghai jianqiang drew inspiration from the artistic trend known as “Chinese Style Graffiti”, which uses Chinese characters instead of Latin letters, reworking the calligraphy in a modern key and adding traditional Chinese symbols. The main theme of the piece revolved around the words Shanghai 上海 and jianqiang 坚强 (fortify, be strong) which are represented through two different styles of charactering, perhaps with the intention of emulating the brush stroke through different degrees of thickness. The part dedicated to the Shanghai 上 海 characters was painted by Huri in a calligraphic style reminiscent of semi-cursive or running script (xingshu). The semi-cursive script is one of the five fundamental scripts used in the art of Chinese calligraphy. In contrast to traditional calligraphy, the characters are written horizontally instead of vertically. Here, it was possible to see a sort of crack in three different parts of the calligraphic writing, to make the piece more innovative and probably symbolise the emotional and physical injury inflicted by the fire. To enhance the characters’ three-dimensionality and dynamism, the piece was surrounded by a shadow rendered through a technique similar to chiaroscuro. The jianqiang 坚强 characters were painted by French writer Storm. His participation in the piece and the use of Chinese characters by a non-Chinese artist strengthened the idea of cross-cultural contamination. The jianqiang 坚强 characters were probably made using a paint roller and tempera or a fat cap (in reference to the spray can cap, which may differ in size; a fat cap allows the thick and fast release of paint and is used to make backgrounds and strokes of a 12 cm thickness and more)25Cap (pentou 喷头) – The cap of the spray can (penqi guan 喷漆罐) is the interchangable spray-can nozzles fitted to the can to vary the width of spray. Its dimension may vary: fat, for large and quick spraying of backgrounds and thick lines; superfat, for ultra quick strokes and large surfaces; soft, or medium- sized, halfway between fat and skinny, for soft, versatile strokes perfect for backgrounds and edgings; skinny, for outlines; superskinny, for precision work and ultra-thin lines.. As a result, the stroke appeared significantly more pronounced and the style seemed to recall the kaishu (regular script), clearer and easier to read, but heavily reworked.

The piece also made references to the Chinese cultural and artistic tradition. At the centre stood an incense jar and four yellow chrysanthemums. Incense refers to the ritual of the funeral wake in honour of the dead, while the yellow chrysanthemum is one of the “four nobles” plants (bamboo, orchid, plum, and chrysanthemum) which, in traditional Chinese painting, represent the four seasons and the four ages of Man; in particular, chrysanthemums symbolise autumn. At the top, an orange horizontal scroll banner read: Rest in Peace 11.15 (referring to the date, 15 November), R.I.P. (acronym of Rest in Peace), and Shanghai be strong. At each side of the scroll there was a small drawing: a black funeral ribbon on the left, a symbol of mourning, and a white peace dove on the right with a bubble style outline26Outline (lunkuoxian 轮廓线) – The letter outline, the contour line of the piece that defines and shapes its structure: the outline put on the wall and then filled, or the final outline done around the piece to finish it. Can also refer to the drawing done in a piece book (see Black book) in preparation for doing the actual piece (see Sketch)., a signature of the old school style27Old school (laoxuexiao 老 学 校) – “Slang” term referring to the subcultures of a discipline or school and its past generations. It is used to compare the current state of a discipline, subculture or movement with a previous stage. In graffiti, it refers to the early years of graffiti writing in the United States (more specifically, the mid 70s to 1983), when numerous styles were invented, making the first writers famous. The expression “back in the day” also relates to this period. Also may refer to hip-hop music of this period. Old-school writers are given respect for being there when it all started, and specific writers are remembered for creating specific styles. For example, Blade and Comet created blockbusters, Phase 2 created bubble letters, clouds, Skeme’s “S”, and so on.. The accurately coloured letters looked like soap bubbles with a large outline. The inline (fill-in) of the letters was generally white or of a lighter shade of colour to increase the sense of depth. The dove was probably chosen to evoke hope and peace. Lastly, at the bottom were the tags of the Oops crew members: Huri and Storm (right and left side respectively), Ting, Snow, Aek, Reign and Redim (in the centre).

Tin.G: post-graffiti with an “ultrafeminine” aesthetic

In addition to being the Oops crew’s sole female writer, Tin.G28Instagram: TinG米小央 (@ting_oops); Behance: TinG 米小央; Weibo: @TinG_OOPS米小央 的个人主页 – 微博. is also Shanghai’s most prolific graffiti artist, famous for her surreal puppets and the use of bright, cheerful colours. But above all, she is China’s most distinguished female graffiti art representative. She was born in 1986 in Shanghai, where she still lives and works as an illustrator and cartoonist. “I started making graffiti in 2006. At that time, I used to listen to hip-hop music, and although I don’t do that anymore, I still love graffiti. It was only after graduating that I chose to become an illustrator, and recently I focus primarily on comics,” she recounts (interview, 2017).

She approached and learned about graffiti writing on her own, mainly out of boredom while still at school. She was 18 when she first decided to hit the streets with a spray can, and she chose a wall in the Minhang district for her debut, a residential neighbourhood near her house in south-western Shanghai. She recalls thinking: “‘I have to try!’ I was excited and scared at the same time, but once I finished my first piece I was over the moon and felt like I had lost my right-hand fingers!” (interview, 2013). Her tag, Tin.G, is nothing more than the transliteration into the Latin alphabet of her Chinese name, Tingting 婷婷.

Over the years, Tin.G has been a member of two major groups: the Oops crew and the all-female CGG crew. She does not consider herself a bomber and does not like to paint graffiti at night or on trains. She has a proclivity for artistic research and prefers to paint in safe, quiet places, such as the Moganshan Road hall of fame. Along with masterpieces29Masterpiece (dafu de zuopin 大幅的作品) – A piece of excellent quality, a particularly successful graffiti. and throw-ups, Tin.G also creates stickers with which to spread her quirky illustrations, thus in some way breaking her vow of “not wanting to be a bomber” (Pic. 22). Stickers are tags made on computer-printed labels. They can either just contain signatures and logos, or be more elaborate. In a 2017 interview she confirmed: “In recent years I have travelled a lot around Asia, where I took every chance to place my stickers on streetlights, walls, road signs, anywhere. Quick and painless. I did it to tell the world ‘Tin.G was here’”. She is the only one, among the artists we selected, to have adopted this peculiar artistic practice, an example of which is the sticker she affixed on a lamppost in 2016 (Pic. 22): a logo-illustration of a somewhat clumsy schoolgirl tripping on a paint container. She is depicted wearing large headphones and carries a paint roller and two spray cans in her backpack. Tin.G places her tag in a little balloon on the right, while in the lower left balloon she writes the exclamation “Oh! Shit!”. Behind the girl’s head, a third balloon contains a musical note. On her sticker, Tin.G also includes two QR codes than can be scanned for easy access to her blogs. The clumsy girl (like nearly all the puppets created by Tin.G for her sticker series) is the artist’s alter ego: she wears casual clothes, listens to hip-hop music, always carries a roller and spray can in her backpack, and clumsily trips over paint, proving that painting – and art in a broader sense – impregnates and pervades her every movement and her entire existence.

Sticker art is a quick form of image-focused communication, the aim of which is to achieve great visibility and make the observer remember the design, logo or symbol depicted, arousing curiosity about the meaning that the sticker carries, thus bringing it close to post-graffiti30Post-graffiti – A modern evolution of the graffiti culture. This first break away from tradition evolved into the graffiti-logo style trend, with artists associating their name to a logo reproduced in series in public spaces through stickers, stencils and posters. Subsequently, more innovative techniques and art forms were introduced, including painting, sculpture, graphics, design, illustration, fashion, photography, architecture, video art and calligraphy. Post-graffiti is the brainchild of a global world, living and spreading over the World Wide Web.. This is an evolution of the graffiti form and culture, which distances itself from traditional perceptions in order to better adapt to the new 21st century media. It first spread through the stylistic trend of the graffiti-logo, in which the artist associates his or her name to a logo reproduced in series in public spaces through stickers, stencils31Stencil art (mubanhua 模 版 画) – A widely used street art practice that allows shapes, symbols and letters to be reproduced in series by means of a stencil, cut in such a way as to form a physical negative of the image to be created. In short, it is a technique characterised by the use of a pattern cut out on cardboard (the stencil) that can be quickly reproduced on the wall with a spray can. and posters32Poster art (haibao 海 报) – A form of street art created by joining sheets of printed paper together to compose a large advertising-style image that can even fill entire building facades.; but it can also cover a variety of more innovative techniques and art forms, such as painting, sculpture, graphics, design, illustration, fashion, photography, architecture, video art and calligraphy. Post-graffiti is the brainchild of a global world, living and spreading over the World Wide Web.

Chinese writers, as explained by Jin Ye and confirmed by Tin.G, share real-time photos of newly painted pieces on social networks, so that they can be instantly found through internet sites or QR codes alongside their graffiti. In this way, graffiti is not only a means for recognition, but an actual springboard that can open up many new life and work opportunities. About the origin and evolution of graffiti writing33Graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) – A worldwide social, cultural and artistic phenomenon born in the 1970s in New York ghettos as a spontaneous expression, with no declared intent, of a heterogeneous group of young people belonging to the hip-hop subculture. The etymology of the word graffito derives from the Latin gràphium, or “style of engraving”, which in turn stems from the Greek gràphein (γράφειν, to scratch, to hollow, to draw). The English term “writing”, instead, stands for the act of creating one’s tag in public spaces using spray paint or markers. It entails a study of lettering, namely the style of the characters that make up both simple tags and pieces. In China, the term “graffiti” does not only refer to the writing of letters or characters as in writing, and thus graffiti is also called tuya yishu 涂 鸦 艺 术 (lit. graffiti art), implying a wide range of artistic expressions on public soil (making it much closer to street art). Another term used is tuya huihua 涂 鸦 绘 画 (lit. graffiti painting), which refers to graffiti containing puppets., Tin.G says:

I think graffiti landed in China around 2000, first in Hong Kong and then in Canton, but I’m not sure. The graffiti pieces in Hong Kong outnumber those in mainland China, because here writers have far more freedom of expression in public places; as a matter of fact, it is not so unusual to see graffiti on trains or building cornices. The spread of graffiti in China was only made possible by the internet: after seeing videos and photos of graffiti by western writers, young people took to the streets and tried to imitate them. The hip-hop culture has also played its part, since almost all Chinese writers began painting graffiti because they listened to hip-hop music or participated in contests34Contest (duijue 对决) – Competition or legal battle between breakers, djs, mcs or writers, the most important of which in China is the Wall Lords Graffiti Battle, or simply Wall Lords (Zhanqiang 战墙). (legal battles or competitions between breakers, DJs, MC or writers) like the Wall Lords35Wall Lords (vimeo.com). This competition arrived in Shanghai only in 2010, fostering many Asian artists with exceptional styles and unusual creative techniques. However, I think street art36Street art (jietou yishu 街头艺术) – A mass media term that tries to define all the art forms performed in public places, often illegally and using the most diverse techniques. Born from graffiti writing, it has developed and evolved into different practices over time: sticker art, stencil art, poster art, video projections, sculptures, installations and performances. in the West is way more mature than its Asian counterpart, perhaps because of its cultural open-mindedness and great artistic tradition. (Interview, 2013)

Defining Tin.G’s style is difficult, as she herself affirms she sets no limits to her art and does not want to box her creations into specific categories: “I don’t know how to define my style; I think classifying an artist’s style is the beholder’s job. While painting, writers simply do what they like, without worrying about belonging to the old or new school” (interview, 2017).

However, it is quite clear that the artist’s relentless intention is to lead the spectator into an imaginary world, a magic wonderland populated by bizarre fairy-tale puppets. Two distinctive elements can be identified in her pieces: the use of bright colours and the presence of figurative elements. In the former case, the warm and bright shades of the letters’ colouring contrast with a lighter or much darker background, conferring unique dynamism to the piece. This juxtaposition between the background and the letters gives greater depth to the graffiti, turning it into a sort of dimensional gateway capable of transporting the spectator into an alternative universe. The eccentric colours of the letters – ranging from red to orange and from light pink to fuchsia and purple – is also quite unusual. These are by no means random; rather, they reflect the idea of femininity and romance that Tin.G sets out to show through her creations. The second distinctive feature is the inclusion of puppets37Puppet (tu’an 图 案) – Figurative elements alongside the graffiti. These may be human figures, animal-like monsters, or comic or cartoon characters (see Character).. Puppets or characters38Character (tu’an 图案) – Animal or human figurative element but also a cartoon figure (usually, but not necessarily) taken from comic books, TV or popular culture to add humor or emphasis to a piece. In some pieces, the character takes the place of a letter in the word. At the early stages of graffiti, characters where corollaries of letters, but over time they have become a style in their own right (see Puppet). are figurative elements – human-like figures or fantastic animals – of a comic or cartoonish nature. In her early works, the puppets were just corollaries to the letters, whereas in her recent pieces, lettering has almost completely disappeared: these pieces are incorrectly referred to as graffiti, when in fact they are illustrations linked to street art. Among her figurative elements we can find a few leitmotifs, such as little hearts, flowers or geometrical patterns that evoke a stereotyped idea of femininity. However, given the structural complexity of her works, the style of her intricate lettering could be considered akin to the three-dimensional wildstyle. Unlike other artists, Tin.G does not always employ the classic shading or chiaroscuro technique to grant depth and substance to a piece; instead, she achieves three-dimensionality by turning the whole piece into a 3D element or placing letters and figurative elements on different levels, always taking the background into consideration. The individual letters, sometimes nestled in other independent elements, are so distorted, intertwined and overlapping that they become indecipherable. However, this is the very challenge facing those who take on a “wild” piece: that of being recognised not only for their name, but also for their own unique and inimitable style. Tin.G’s mode of expression is only partly ascribable to “Chinese Style Graffiti” because the artist does not employ Chinese characters in her pieces, but she does include – at times covertly – numerous elements of Chinese culture and tradition.

An example that perfectly sums up the artist’s style as we have just described it is The Lotus Boy, which openly evokes Chinese symbolisms. This graffiti was painted by Tin.G on the walls of Moganshan Road in the summer of 2009: “Lotus Boy is one of my first pieces and the one I’m most attached to: it is dedicated to my favourite mythological character, Nezha. This deity is also known as the ‘Lotus God’, which is why the letters are painted in pink and you can see lotus leaves all around them” (interview, 2017).

Nezha or Na Zha (Nezha 哪吒) is a patron deity of Chinese folklore. His official name in Taoism is the “Marshal of the Central Altar” (Zhongtan yuanshuai 中坛元帅), but he is also known as the “Third Lotus Prince” (Lianhua santaizi 连花三太子). The entire graffiti is linked to the theme of the Lotus. In Chinese culture, the Lotus has multiple meanings inspired by its features and properties. In Buddhism, its symbolism ranges from divine purity to enlightenment. For the Asians it carries a strong spiritual significance due to the fact that it sinks its roots into muddy water, sprouting in all its immaculate beauty to rest on stagnant waters: for this reason, it symbolises those who live in this world without being contaminated by it. In Tin.G’s piece, the colour of the letters, the leaves in the outline, and the background all make reference to the lotus flower in their own special way. The rather wildly tangled lettering replicates the word Nezha, and its fill-in (the painted area inside the letters) plays with the different shades of pink (from purple to fuchsia and white) of the Lotus flower’s petals. Then, the first magenta outline of the letters is flanked by a second green outline made using a much thicker stroke. Green lotus leaves are placed around it, resembling Pacman-like figures from the popular video game. Finally, the chromatic contrast between the pink letters and the black background is probably a reference to the unusual hydrophobic ability of this wonderful flower, which manages to remain clean despite growing in stagnant waters. In this graffiti, we even catch a glimpse of loops, decorative elements often used in wildstyle to join letters and add dynamism to the piece. The work entitled Pink Africa (Pic. 20) is also rooted in the theme of femininity, albeit linked to a social message. Like Shanghai jianqiang (Pic. 18), Pink Africa is dedicated to the victims of the 2010 fire in Shanghai.

The central lettering is made up of the word Belief, perhaps to solace the victims’ families and loved ones. Around it, Tin.G places three balloons with the wordings Oops, Mourning for 11.15 Victims R.I.P. and TIN.G. Her tag is repeated twice more, on the lower right and left respectively; Tin.G paints the three tags in three different styles, possibly to highlight her closeness to and emotional support for the victims of the fire. From a purely stylistic point of view, the piece could be said to fall within wildstyle graffiti, the originality of which may be attributed not only to the bold interlocking and overlapping of the letters, but also to the use of a paint drip pattern and cracks between the letters. The brown and beige background reproduces an African landscape on two levels – presumably a reference to the heat of the fire, also evoked by the cloud of smoke above the letter E. To brighten the piece, the artist adds a “broken” yellow outline to the first one in black, as well as shades of white inside the corners and curves of the letters. The fill-in is bright pink, with light and dark pink maculated spots on a red background in three letters. The maculated pattern resembles the leopard’s fur, a plausible nod to the African theme, and stretches all the way to the double outline.

In The Rabbit Year (Pic. 21), Tin.G refashions elements of Chinese folklore.

This graffiti portrays the word Love and five white rabbits on a background depicting an enchanted forest. The artist painted this piece in 2011 in Moganshan Road, as her personal wish for a happy Chinese New Year (the Year of the Rabbit) and Valentine’s Day (the Lunar New Year is usually celebrated around the 14th of February). In addition to the word LOVE, the leitmotif of the heart is also present, as an explicit reference to the day of lovers. The lettering is barely readable, and therefore similar to wildstyle, but with a very bright fill-in colour that plays with different shades of yellow, red and orange. The thin white outline above the main black one and the white shaded corners and curves of the letters add brightness to the piece. The puppets consist of five white rabbits timidly and fearfully emerging from the letters. They represent one of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac and, in this particular case, are linked with the year 2011, when the piece was made. The Chinese zodiac is based on 12 cyclical years; each year of the cycle is associated with an animal: mouse, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig. The rabbit (tu 兔) is the fourth animal in the 12-year cycle. According to traditional Chinese astrology, the rabbit is cautious, quiet, reserved, self-absorbed, contemplative and lucky. The artist also fits a small heart within the letter E, while on the outside she places her tag and that of the Oops crew, of which she was a member at the time. The piece’s three-dimensionality is achieved by transforming it entirely into a 3D element by means of a chromatic contrast within the letters, without actual shading, and through the use of perspective in the background, where the lettering almost looks like it is comfortably “seated” on the lawn. The cartoonish rabbits have pink eyes like the White Rabbit of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, symbolising the dreamlike dimension that leads Alice into an unrestricted world in which irrationality reigns supreme. Possibly, the aim of these five rabbits is to lead us, the viewers, into Tin.G’s wonderland. The choice of the number five might be linked to the “five elements” (wuxing 五行): wood, earth, water, fire and metal. These are core concepts of Chinese culture, also applicable to medicine, dictating the pace of nature and mankind. This hypothesis is perfectly in line with the idea of a ubiquitous, universal love, and links to the concept underlying all of Tin.G’s work.

In 2013, the artist joined CGG (which stands for China Graffiti Girls), China’s first all-women crew currently comprising six artists: Rainbo (from Hong Kong), MT (from Hainan), Mizi, 399diskr and Satr (from Canton), and Tin.G:

China Graffiti Girls was founded in 2013 by six female writers living in China and Hong Kong. The graffiti scene in Asia has grown significantly over the past decade, but street art remains a predominantly male art form. In the past ten years an increasing number of female artists have started to stand out and receive the attention they deserve. (Interview, 2016)

The CGG crew’s aim was to paint fresh, delicate pieces imbued with femininity, in response to the enduring male dominance in Chinese urban art. The colours, the style of the lettering and the puppets used show the “ultrafeminine” nature of their aesthetic: one that is far more delicate, soft and emotional than its male counterpart. The choice of the crew’s name is also fully in line with this approach. As stated by Tin.G, their work as a crew belongs to street art in a broad sense, although all the members debuted with the illegal bombing of writing pieces. Their artistic practice fluctuates between collaborations with famous brands and participations in urban decoration works coordinated by the local authorities. The crew has taken part in many graffiti-related events, such as the Meeting of Styles39Meeting of Styles is a non-profit organisation that hosts and sponsors graffiti-related events around the world. The first Chinese event was held in 2011., and their first exhibition, the Yo Girls Graffiti Exhibition, opened in Hong Kong in 2015. This was set up inside and in the vicinity of the art gallery Part of Gallery, in Sik On Street, Hong Kong. From 31 August to 4 September 2015, the CCG crew painted five pieces on the street, while in the gallery visitors could admire and buy sculptures, photographs, paintings on canvas, and various gadgets made by the artists.

Although all the members of the crew are worth analysing, the leader Rainbo deserves a special mention. Born in the Hunan Province, she now resides in the city of Hong Kong. She is also one of the founders of the AWS crew (an acronym for After Work Shop), along with Uncle, a Hong Kong writer and artist with whom she very often paints. Like many Chinese graffiti artists, over the years Rainbo has experimented with several artistic mediums, from oil painting to sculpture, graphic design, ceramics, model building and illustration. She has painted at the halls of fame of every major city in China, including 798 Art District in Beijing and Moganshan Road in Shanghai. From a stylistic point of view, Rainbo predominantly employs her own bubble style, in which letters come to life and become puppets with eyes, arms and legs. The colours in her pieces are bright and eccentric, and often enriched with colourful backgrounds. The parallelism with Tin.G is therefore immediate: on a stylistic level, both Rainbo and Tin.G usually prefer cheerful, feminine colours, giving their creations a fun yet elegant vibe. Likewise, albeit in different ways, they both paint puppets and figurative elements, the quality of which have turned them into acclaimed professional illustrators. Ultimately, throughout their careers both have revealed an urge to broaden their creative horizons by switching from writing to other artistic forms, and vice versa, something quite common among post-graffiti Chinese artists who seek to move beyond and modernise traditional writing.

In China, renewal is constant; things die and rise again in the space of a night (including skyscrapers). The urban fabric is subject to continuous changes, and street art is no exception. In big cities, particularly in Shanghai, this factor has allowed for lightning-quick development. In the same vein, graffiti is as fleeting as the canvas it is painted on; it can only be immortalised by photography and new online platforms. Nearly all writers have artistic backgrounds, and use the streets to reinforce their image as urban underground artists and create new job opportunities. Finally, it is evident that the cosmopolitan and multicultural soul of the city of Shanghai has allowed a sort of contamination between local and foreign artists, providing fertile ground for creativity.

This new trend is embodied to perfection in the figure and work of Tin.G: her early adhesion to the hip-hop culture, the visual propaganda of her stickers, her evolution of puppets into out-and-out openair illustrations, and the use of QR codes alongside her works, are just a few examples of the new way of conceiving graffiti art in China. An analysis of her works also reveals another peculiar element: a sharp contrast between the boldness and excellent mastery of the wildstyle used for her lettering, and the marked delicacy of the figurative elements that accompany it, as if she wishes to leave a feminine, romantic impression at all costs. In this regard, Tin.G is the forerunner of an exquisitely “ultrafeminine” aesthetic in Chinese graffiti art, which makes use of vivid colours, female stereotypes, and pop references to brighten up an otherwise grey urban jungle.