III. BEIJING: CAPITAL OF CHINA, CAPITAL OF GRAFFITI

Adriana Iezzi

Beijing is a megalopolis where more than 21 million citizens live today: more than one third of the entire Italian population and almost as many inhabitants as the whole of Australia. This makes it the most populous country capital in the world! Today, 20 underground lines navigate the city, while up until 2007 there were only two. This speaks volumes about both its territorial extension and the rate at which the city evolves and transforms: a supersonic speed that we can hardly imagine. From an administrative point of view, Beijing lies at the centre of the Municipality of Beijing, an autonomous region covering a territory of about 16,400 km. The city is the political centre of mainland China, home to the National People’s Congress and all major Chinese institutions, where the most important decisions for the entire nation are taken.

It was founded under the Mongol Empire (the Yuan dynasty, 1271-1368) and named Dadu, or “The Great Capital”. In 1421 it became the capital of the Ming Empire (1368-1644) with its current name – Beijing 北京, or the “Capital of the North” – and has almost uninterruptedly retained this role ever since. Despite being the capital of the oldest empire in the world, Beijing, about 600 years old, is relatively young (Pisu 1976, pp. 15-16). Its founding is linked to a legend: the geometric perfection of its plan is the earthly translation of divine images that appeared in a dream to the Buddhist monk who was the tutor of the emperor Yong Le (1360-1424) who founded the capital during the Ming dynasty. One night he dreamt of a splendid otherworldly city – the residence of the Lord of Heaven – and suggested that the emperor draw inspiration from its pattern to build the new capital. Yong Le faithfully adhered to this divine vision in order to reaffirm the close relationship between Heaven and the emperor, called the Son of Heaven. Just as the Lord of Heaven lived within a Purple Enclosure, a constellation of celestial bodies clustered around the North Star, so on earth the Son of Heaven must live in a purple city protected by walls, representing the centre of the earthly world.

The Forbidden City was thus erected: an Imperial palace enclosed by purple-coloured walls – the centre of the city and the power core of the entire empire (ivi, p. 19). Up until forty years ago, all around this splendid residence with golden roofs (the colour of the emperor) was nothing but an endless expanse of one or two-storey houses with low curved roofs: in between geometric blocks, the tangle of dusty hutongs – Beijing’s traditional unpaved alleys – was a succession of grey blind walls (ivi, p. 29). Aside from the Forbidden City, only a few other temples and monuments scattered here and there would dot the sea of greyness: the Temple of Heaven, the Drum and Bell Tower, and little else. For Le Corbusier, the geometric perfection of the city layout and its plan made up of a set of straight lines intersecting at regular distances, represented the urban model of human perfection, as opposed to the city of Paris, entirely composed of irregular curves. According to the architect, it was indeed unthinkable that an “imperfect” city like Paris could claim to bring civilisation to a “perfect” city like Beijing (ivi, p. 19).

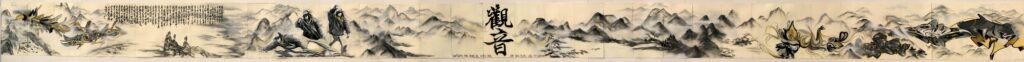

And yet, what remains of ancient Beijing today? Very little: it is a towering mass of ultra-modern skyscrapers in which the heights of the Forbidden City are lost and dispersed. All that is left of the hutongs and old neighbourhoods are fragments, since (almost) everything has been swept away by the fury of modern China’s bulldozers. The perfect tangle of orthogonal alleys has been overlapped by a series of motorway loops that expand well out of proportion and develop at the same unstoppable pace as the city. Still, the greyness remains, caused by the haze of pollution that constantly hovers over the city. This, however, is contrasted by the lively cultural scene that characterises the city. Beijing is one of the preeminent centres of culture in China, and in some respects the most important. It is home to the major governing bodies of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Academia Sinica (Pisu 1976, pp. 34-35), as well as no less than 91 university-level higher education institutes, including Peking University and Qinghua University, which are listed among the best in the country. Beijing is also home to the China Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), China’s most prestigious art academy which has trained some of the greatest contemporary artists in the country (e.g. Xu Bing, Zhang Huan, Zhang Hongtu and Hong Hao), and to many other art and design academies attended by talented graffiti writers. In addition, Beijing has more than one hundred museums, including China’s most distinguished institution of modern and contemporary art, the National Museum of China (NAMOC), which has hosted the country’s most important exhibitions in the last forty years. Here, after being banned from exhibiting their ground-breaking works in 1979, the group of artists Stars (Xingxing) decided to display them on the museum gates, giving birth to Chinese dissident and avant-garde art. Ten years later, in 1989, the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition took place precisely at NAMOC. It was the first exhibition in the country dedicated to experimental art, with the aim of presenting the public with a complete overview of the works produced by the new Chinese artistic currents in the last decade. This step-up in exhibitions also concerned (and continues to concern) graffiti art. It was in fact at the CAFA Art Museum that China’s first international exhibition dedicated to graffiti and street art took place in 2016, entitled Art from the Streets (The History of Street Art – from New York to Beijing), with artists from the United States, Brazil, Great Britain, France, Italy, Portugal, Senegal, and, of course, China.

Beijing is thus confirmed as the heart of contemporary Chinese art development. In the last few decades, numerous galleries have opened their doors, joining the wave of eager interest in contemporary Chinese artists by international auction houses, collectors and museums from all over the world. In the second half of the 1990s, only a shrewd handful of galleries had realised their fruitful potential and created independent showcases for artists who previously had had very few opportunities to show their works to the world (Marescialli 2008, p. 23). In Beijing we find the country’s most important districts dedicated to contemporary art: Yuanmingyuan artists’ village, Songzhuang art community, 798 Art District and Caochangdi. These last two are particularly important for graffiti art. 798 Art District, located in the north-eastern part of the city, is an old state-owned industrial complex designed in Bauhaus style in the 1950s by a group of East German architects, which once housed a production line of electrical components for military use. In the early ’90s it was closed due to financial difficulties, but in 2000 it started to repopulate, attracting to its large (and cheap) spaces a growing number of local artists looking for places to set up their studio. Within a few years, it became “a sort of Chinese Greenwich Village” (Curcio 2015, p. 10), a “post-industrial-chic community made up of artists, designers, media people and white collars” (Marescialli 2008, p. 59), turning it into the first art district in the city. Today, the district houses contemporary art festivals, studios and dozens of independent artists’ homes, including painters, sculptors and photographers, several national and international galleries, museums, like the famous Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCA), art bookshops, designers’ studios, cafés, magazine newsrooms, and a number of local and international companies’ offices. It is also a central district for the spread of graffiti art in Beijing. Indeed, 798 is one of the areas where the first graffiti in the capital appeared: the studio of the Kwanyin Clan, one of the first and most important graffiti crews in Beijing, was based there, as well as China’s first graffiti store 400ML, opened in 2012 and run by the ABS crew. For the last 15 years at least, this is also the place where the city’s graffiti crews and writers have been meeting to create pieces on the buildings’ walls, and where various graffiti festivals are hosted. Among them, the most important is the annual Meeting Neighbourhood, which brings together artists and graffiti enthusiasts from all over the world.

The Caochangdi district, located about 20 km away from the city centre, is the second key art district in Beijing (after 798). Since Ai Weiwei (Beijing, 1957) chose to move his studio to Caochangdi in 1999, numerous other artists and galleries have followed, notably Chambers Fine Art, Ink Studio and Taikang Space. Unfortunately, since July 2018 the art district has been partially dismantled: many galleries and art studios, including Ai Weiwei’s, have been demolished or forced to relocate (Mouna 2018), leaving a large void in the artistic fervour developed in the area. The district is also a significant location for Beijing’s graffiti art, as it was home to the studio of the city’s and mainland China’s first graffiti writer, Zhang Dali1Zhang Dali worked in several studios: first in Yuanmingyuan in Beijing, then in Bologna, and then again in Beijing in Dongsi Shier Tiao 34 (during his graffiti period), Liulitun, Maizidian, Caochangdi – which was one of the most important, Heiqiao and now in Zhubaotun 1-3: http://www.zhangdaliart.com/en/studios.html (last accessed in February 2024)., and of Beijing’s first graffiti crew, Beijing Penzi, where its members painted skateboards and other similar items for commercial purposes (Feola 2014).

Beijing’s cultural and artistic turmoil, as well as its reputation as a postmodern hyper-commercial megalopolis pervaded by grey concrete and unbreathable air, made it the ideal setting for the development of graffiti art in China, also thanks to the spread of an underground culture that has flourished in the city since the 1990s. Today, the city seems to be the ideal setting for multicoloured and sometimes provocative graffiti that break its leaden monotony. It is no coincidence that the first manifestation of graffiti art in mainland China appeared precisely in Beijing.

The birth and spread of graffiti in Beijing

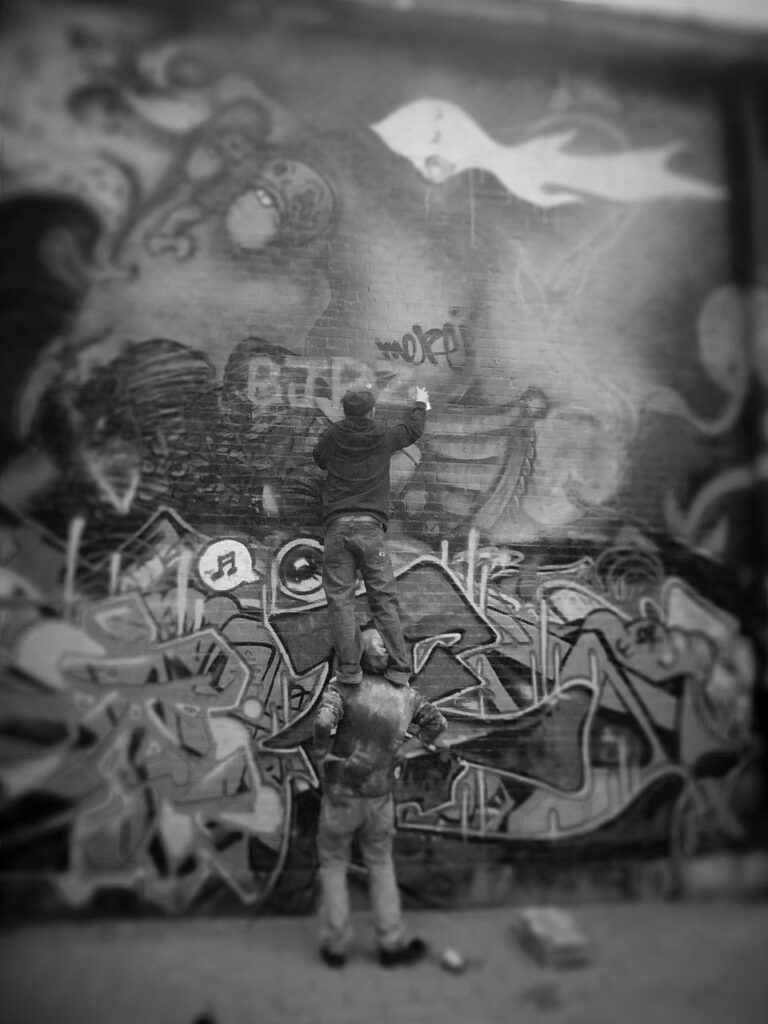

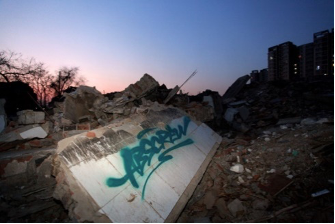

Graffiti art was introduced to Beijing by Zhang Dali, who embarked in 1995 on the artistic project Dialogue and Demolition (Duihua yu chai 对话 与 拆 , 1995-2005) (Fig. 2): he spray-painted more than 2,000 giant portraits of his head’s profile on the walls of buildings destined to be demolished, often accompanying them with the tags2Tag (qianming tuya 签 名 涂 鸦) – The pseudonym, stage name, or code name that every graffiti artist, mc and breaker uses to distinguish themselves, to stand out and highlight their presence in the city. Being the most basic form of graffiti, created with spray cans or markers, the tag is the backbone of the writing phenomenon. The evolution of the tag represents the personal style of its author. All pieces, even the largest, most colourful and elaborate ones, remain, in essence, signatures. The activity of marking a surface with a tag is called tagging-up, while tag bombing is the reproduction of one’s tag on a large scale in a certain area of the city. Tags can also be representative of entire groups. Different writers or mcs who join together can decide to use one comprehensive tag, as a symbol of the group (see Crew). AK-47 or 18k (abbreviations for Kalashnikov and 18-carat gold) (Wu 2000; Marinelli 2004). This artistic and photographic project, which triggered heated debate in Beijing in 1998, was intended to draw attention to the disturbing trend of demolishing entire districts of the old city with their history and the stories of the people who lived there. Its goal was to warn citizens about the side effects that modernization was bringing about in China (Curcio 2015, p. 71). The choice of its two tags (AK-47 and 18K) was by no means incidental: the abbreviation of the Kalashnikov recalled the idea of violence inflicted by the government on the city and its citizens; while the 18K gold was a reference to the power of money and the pursuit of wealth that was distorting Chinese society and culture. The idea of creating the first graffiti in the city was the result of the six years Zhang Dali spent in Bologna, where the artist moved after the tragic events in Tiananmen Square in 1989. In Bologna, the artist had taken part in the city’s intense artistic activity. Here he was introduced to graffiti writing for the first time, by which he was profoundly inspired. Once back in China, he realised the havoc that was being wrought there and decided to apply what he had learnt in Italy to the walls of Beijing. It may be said, therefore, that if graffiti art has managed to make its way into the Chinese capital, it is also partly due to Italian influences.

Although Zhang Dali is usually considered the “Godfather of Beijing graffiti” (Bonniger 2018, p. 21), some experts disagree. According to them, the first graffiti writer in the city was not Zhang Dali, who is regarded as a street artist rather than a writer, but Li Qiuqiu 李球球, known as 0528 (Fig. 3), who started his activity in 1996 (see Video section, film Crayon 2012; for Zeit see Mouna 2017). They argue that Zhang Dali’s work had no impact on the following generation of writers, since he always worked alone without interacting with other artists, and only practiced graffiti for a short period of his career (1995-2005), later moving on to other forms of expression – indeed, he identifies himself as an artist rather than a graffiti writer (film Crayon 2012; Valjakka 2016, p. 361). Li Qiuqiu’s work, instead, had a strong impact on the following generation: he has always interacted with young Beijing writers and, being a pioneer in this field, founded one of the city’s first and most important crews: the Beijing Penzi (Mouna 2017).

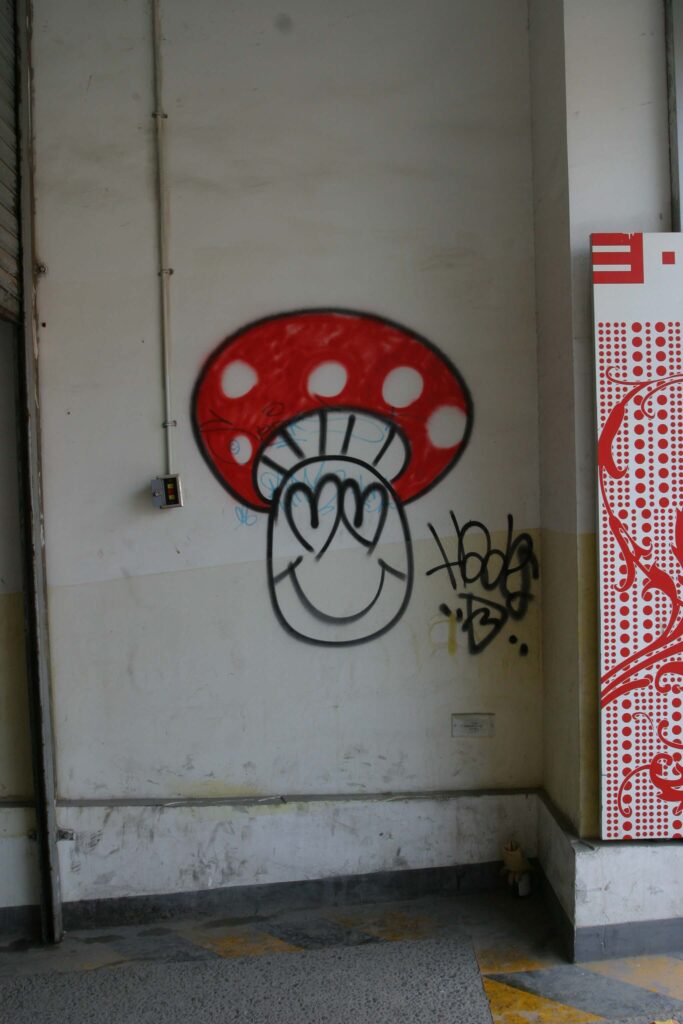

Regardless of the “rightful” authorship of the first Beijing graffiti, for about ten years Zhang Dali and Li Qiuqiu were unquestionably the only known writers working in the city (Valjakka 2016, p. 361). The next generation of graffiti writers appeared on the scene only in 2005, partly thanks to the establishment of The Great Wall of Beijing, he city’s first hall of fame3Hall of fame (tuya qiang 涂 鸦 墙) – A space where graffiti writing is (more or less) legal. Halls of fame are mainly popular with writers who aim to create artistic, sophisticated pieces, favouring quality over quantity and constantly searching for original styles. located on the southern side of Renmin University, a major university in the capital. The wall and its graffiti, or pseudo-graffiti, were all dedicated to the Beijing Olympic Games (Bonniger 2018, p. 22) to be held in August 2008: a momentous event for the entire country. The wall was 700 metres long and about 300 volunteers took part in its decoration (Llys 2015)4The wall was established on 11 December 2005. According to Llys, before the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in 2014, it was entirely painted in red, covering all works created since 2005.. The success of this large-scale project, supported by the government with evident propaganda purposes, increased curiosity and helped to spread interest in graffiti throughout the city, from public opinion and art circles to young art academy students. As a matter of fact, from 2006 onwards, individual graffiti writers started to gather, founding the first crews like the aforementioned Beijing Penzi and Kwanyin Clan. Besides, other street artists started writing individually, like Hades or The Little Mushroom (Xiao mogu 小 蘑 菇 ), who was very active in bombing5Bombing (zhajie 炸 街 / beng 崩) – Filling walls and trains with illegal graffiti, typically throw-ups, tags, stencils or simple lettering pieces that can be executed quickly. This is the favourite practice of writers whose primary aim is quality, and who cover the city with their tag to attain the fame of king. the 798 Art District, Sanlitun and the city centre. Most of his works consisted of a cartoon-like mushroom, usually depicted donning a red hat with white polka dots and a smiley face with various expressions on the stem. In keeping with the finest urban graffiti tradition, the artist’s identity is still unknown. We only know he is a designer, tattoo artist and skateboarder, which is quite common among Chinese graffiti writers.

Another important artist at that early stage of graffiti development was Xu Ruotao 徐若涛, who created graffiti in the district of Tongzhou in 2004. His writings were subsequently published in Art World, an important Chinese contemporary art magazine, marking an all-time achievement for this art form. Together with Li Qiuqiu, Xu Ruotao is a pioneer in the use of Chinese characters in his pieces: in one of his works created in 2004 near the Bali Qiao underground station on line 1 East, he wrote Mei ge ren dou shi shibaizhi 每个人都是失败者 (All men are fallible). Although the writing style is still very rudimentary, it is one of the first graffiti works entirely in Chinese characters in Beijing.

In those early years of graffiti development in Beijing, the favourite spots for graffiti writers were the 798 Art District, the Sanlitun shopping district, which is very popular among foreigners, the Wudaokou nightlife district, filled with bars and clubs, a few areas in the city centre, mostly those at risk of demolition, and the China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Beifu 北服), the oldest non-state-established graffiti hall of fame in the city (Crayon film 2012)6Llys affirms that the China-Japan Friendship Hospital became a graffiti wall in 2005. This is confirmed by an article about Su Bin 苏滨 in the art magazine Sculpture.. Ever since 2007, an increasing number of foreign graffiti writers has arrived in the city, introducing new styles and techniques and massively influencing the Beijing graffiti scene (Bonniger 2018, p. 23). Among those writers, we should mention Zyko (Germany) and Aigor (Europe), who “were showing them [the Chinese writer] the mental or internal side of graffiti” (Feola 2014). Zyko first came to Beijing in 2006, when there were few graffiti around, as he says, and then again in 2008, when the scene was much more active and had completely changed, mainly due to the intense activity of the Beijing Penzi crew. He thus decided to move to the Chinese capital in 2009 (film Crayon 2012). He mostly works alone, in search of his own style, but sometimes also collaborates with local and foreign writers (Valjakka 2016, p. 363). According to Zyko, one of the major problems of making graffiti in China is excessive costs: while spray cans are cheap, they are of extremely poor quality and last three times less than the European ones. He calculated that it costs around 20 euro to make one piece, which is a considerable amount for a Chinese person, meaning only those with adequate financial means can approach this form of art (film Crayon 2012). In terms of style, according to Zyko, the foreign writers who had the greatest impact on Beijing’s artists were the German Cantwo (a.k.a. CAN2) and the American Revok (from the MSK crew), also through their work in the city, as well as the AWR crew from Los Angeles (Valjakka 2016, p. 363).

In an interview, Aigor, active in Beijing for a couple of years mostly with his bombing activity, highlights another difference between China and Europe: although creating graffiti in China is dangerous, it is far easier than in Europe. Since this art form is still poorly known among the Chinese, there is little repression and much curiosity surrounding graffiti (film Crayon 2012). In Europe, writers can take two to five minutes at most to create a piece without being discovered, while in Beijing they can take even up to an hour. Zyko agrees with this view: he speaks of a form of “nice anarchist feeling in the street” that cannot be found in any European city. This form of freedom is the reason he does not want to leave Beijing (ibid.).

Other foreign writers present in Beijing in recent times are Mike (a.k.a. Iron Mike), from Stockholm, who has been active since 2011, the Italian Sbam, who arrived in 2012, and Zato, who came in 2013 and is still very active in the city today. What is special about Zato is that he frequently uses Chinese characters in his pieces: most of his works consist of bubble style7Bubble style (paopaozi fengge 泡泡字風格) – Rounded, old school style lettering, still extensively used in throw-ups due to its quick execution. The letters recall soap bubbles and are painted with great precision. The outline is usually thick, with a white inline to enhance the depth of the lettering. Phase 2 originally created this style. two-colour throw-ups8Throw-up (kuaisu tuya 快速涂鸦 / outu 呕吐) – The first evolution of the tag; a stylised drawing of one’s signature, quickly executed but on a large scale, with few colours that are usually sprayed roughly, even without fill-in. The throw-up is an art of its own: the style is immediate, often very simple and “rubbery”, yet never banal. It only consists of an outline with a monochrome fill-in, but the term can sometimes also indicate any kind of bubble style, thus not necessarily monochrome. This technique is scorned because it is deemed unesthetic, but achieving a good throw-up, quickly and with a precise outline, is no easy task. The throw-up is also known as a flop. Throw-ups can be from one or two letters to a whole word or a whole roll call of names. Often times throw-ups incorporate an exclamation mark after the word or letter., in which he transcribes the two Chinese characters Zatou 杂 投 , representing his Chinese tag, often accompanied by a caricature of a stylised man with cross-shaped eyes and a beak-like mouth. His ideal surfaces for writing are shutters, walls and roofs of shops and restaurants, while his favourite areas are those of the hutongs of the old city. Sometimes Zato also enjoys writing entire sentences or idiomatic expressions in Chinese characters with enigmatic meanings, such as Wo bu yao guoqu, wo bu yao weilai 我不要过去, 我不要未来 (I don’t want the past, I don’t want the present), Hen huang, hen baoli 很黄很暴力 (Very yellow, very violent), and Mei you yiyi 没有意义 (Without meaning), giving his works a mysterious aura (Feola 2013). The choice of employing Chinese characters in his pieces stems from his desire to make his art accessible to as many people as possible, and this, in his opinion, can only be achieved through the local language. According to Zato, graffiti has no special meaning and should have nothing to do with money, business, or art. Its only aim is to give passers-by the unexpected opportunity to come across new, striking sights (Huang 2016).

New generations: the KTS crew

Due to the international buzz surrounding the graffiti scene, new crews have been sprouting in Beijing since 2007, some long-lived and others with a very short lifespan. Among the latter, we should mention Jiu Men 九 门 (Nine Doors), which was founded in 2007 and disappeared the following year, and the Beijing xinshengdai tuyazhe 北京新生代涂鸦者 (Beijing Cenozoic Writers), formed by university students and active from 2007 to 2009 (Llys 2015). Other more successful crews, which are still active today, are ABS (founded in 2007), KTS (2009), DNA (2010), TMM (2011), Tuns (2013) and YDS (2016) (Bonniger 2018, p. 23).

The KTS crew was founded by Mes and Boers, joined first by Wreck and later by Exas (a.k.a. Swe). This is one of the most respected crews in all of China (Crayon 2017). Its four members are old-school writers, and their activity mainly consists in bombing the city streets (Valjakka 2016, p. 362). Most of their work focuses on the crew’s acronym (KTS), which stands for Kill The Streets, later changed to Keep The Smile, or their names tagged-up in Latin letters, alongside bubble style or simple 3D style93D style (litizi fengge 立体字风格) – A three-dimensional style of letters, used to add effect on basic letters (enhancing depth and allure in the piece), sometimes applied to wildstyle for an extra level of complexity. In graffiti writing, the most widely used technique for 3D is chiaroscuro. To implement it, the artist first chooses the direction or vanishing point, then, starting from the edges of the letters, draws same-length guidelines following that same direction. Subsequently, the artist connects these guidelines, drawing lines that run parallel to the letter lines, and finally the area is filled with colour. The effect could be achieved by shadowing the letters, but this procedure is far more complex. This style was invented by Phase 2. blockbusters10Blockbuster or block – This is a kind of graffiti that is easy to execute. It is made of large, square or rectangular block letters. It is generally two-toned: one colour for the fill-in (using temper, roller or paintbrush) and one for the outline. Mainly invented to cover over other people and to paint whole trains easily, but they are effective on smaller walls for maximum coverage. Blade and Comet claim to have invented these. and throw-ups. Nonetheless, early in their careers (and beyond), Mes and Exas, in particular, produced numerous graffiti of their Chinese tags in Chinese characters – Fengji 疯 奇 (crazy, weird, funky) for Mes and Lingdan 灵 丹 (panacea, soul) for Exas – using different styles, from the more graphic (and calligraphic) to the more elaborate.

According to Mes, who is now 33, his first encounter with graffiti dates back to 2006, when he was still a high school student: after seeing graffiti on the Internet, he decided to pick up the spray can for the first time. From that moment onwards, graffiti became his purpose in life, and he never gave them up. At the beginning, his goal was to decorate the city by creating aesthetically appealing pieces, but he soon understood the sharp difference between “painting a wall” and “writing graffiti”, and started bombing difficult, dangerous places, creating his own distinctive style. About a year and a half after he started making graffiti he met Boers on Baidu Tieba, China’s most important online platform, and they started bombing together. At the time, Boers was a computer science student two or three years older than Mes, who used to paint cartoon style mice. During a graffiti competition in October 2009, Mes and Boers decided to found the KTS crew. Utterly engrossed in his new life, Mes quit high school during his third year so that he could spend every night bombing the streets of Beijing. Together with Boers, he set up a company through which he could use graffiti for commercial purposes, but the venture failed. Mes’ parents then started to put pressure on him and forced him to attend various design schools, until they decided to send him to university in Great Britain. Once back in China, again under pressure from his father, Mes started working in a design company, and has since been seen more and more sporadically painting graffiti along the streets of Beijing. A year younger than Mes, Wreck approached the graffiti world in 2008, thanks to the propaganda for the Beijing Olympics and the exponential rise of illegal graffiti in the city. He met Mes in 2009, once again through the platform Baidu Tieba, when KTS was the most important and active crew on the streets of Beijing. Wreck started an intense night-time bombing activity, together with the other two crew members, even venturing to write on trains, which is quite rare in China. The crew initially focused its efforts on the Haidian University District, one of Beijing’s key areas, home to the Summer Palace and the Old Summer Palace, where the three writers lived. Later on, they expanded their reach to the entire city. As stated by Wreck himself, the choice of his name is rooted in his desire to have his tag begin with a “W”, since no one had used that letter before, as well as in its meaning, evoking the concept of “ruin”, which comes close to the perception of what graffiti is for him: a thorny presence in an ordinary landscape (Huang 2016).

Because of his intense bombing activity, Wreck has been repeatedly arrested and released on bail, also with the help of his friend Boers. Today, he is a tattoo artist and owns a studio called Delight (Dengta 灯塔) located at 46 Fajia Hutong, an alley near Gulou East Street in the city centre, where he brings elements borrowed from graffiti art into his tattoos. His studio is also an important centre for the propagation of graffiti culture and a meeting point for Beijing writers, many of whom have become close friends of his. Although much less frequently than in the early years of KTS, until a few years ago Wreck could still be seen night-time bombing together with Giant (YDS crew), producing about one throw-up per month. Today, he is out of the scene. He has stated that he has not time to draw on the streets due to various family and work commitments, severe government restrictions, and the increased police monitoring of recent times. Exas was the last to join the crew but, after a very intense period of activity, he moved to New York to attend American schools. There he instantly saw the stark difference between doing graffiti in New York and in Beijing. As Exas says: “I couldn’t do anything too complicated or intricate because [in New York] I never had more than ten minutes to throw something up.” […] “In Beijing I didn’t care who was watching me because when I painted I felt like a god” (Crayon 2017).

Young crews, including women

The DNA crew revolves around the figure of its leader Daboo (Dabo 大波). Born in Beijing in 1989, Daboo started writing graffiti in 2005. Up until 2017, when he became a father, his main activity took place at night in the Daxing District, located in the southern part of the city. Here, he filled walls, bridges, and the rubble of demolished buildings with his tag, spray-painting simple to elaborate pieces (Yau 2018). In 2010, he founded the DNA crew together with other two writers. Their aim was to make graffiti for commercial purposes, decorating gyms, cafes, schools, and restaurants. As a result, most of DNA’s works are elaborate pieces with an “international” flavour, consisting predominantly of the use of English (the works in Chinese characters are rare) and western puppets11Puppet (tu’an 图 案) – Figurative elements alongside the graffiti. These may be human figures, animal-like monsters, or comic or cartoon characters (see Character)..

TMM (The Marginal Man, also known as The ManageMent) was founded at the beginning of 2011 by Clock and Dios, joined shortly afterwards by Gan, Camel and 525. Three members of the crew are not native of Beijing: one is from the Hubei province, one from the Hebei province and one from Canton (Valjakka 2016, pp. 362-363). The crew does not seem to be active anymore, although three of its writers, Clock, Camel and 525, continue to work individually. Clock mostly creates elaborate pieces, sometimes accompanied by puppets, and frequently works with the female writer Sick. To him, graffiti is a form of entertainment rather than rebellion against the system (see Video section, film Crayon 2012). 525, whose tag is based on his date of birth, prefers the activity of bombing, transcribing his tag also in large scale works. He often collaborates with Wreck of the KTS crew and is the author of some works in Chinese characters.

Camel (a.k.a. Camel617) is extremely good at painting cartoon style puppets with distinctly Chinese features: his characters are often portrayed eating or drinking local delicacies such as Peking duck or Chinese schnapps. These puppets are usually accompanied by balloons with Chinese writings in a very personal graphic style, a sort of title indicating the theme of the piece. He uses the same style in his spray-painted red square seals recalling those used in calligraphy or traditional paintings. Graffiti are a form of rebellion for Camel – although, like all Chinese writers, he knows that there are boundaries that should not be crossed, so he is careful not to paint his works in sensitive places such as Tiananmen Square or on government buildings and is always cautious about the subjects he portrays (Sebag Montefiore 2014). His 2009 work, spray-painted on a wall in Beijing, in which he portrayed an “urban inspector” (chengguan 城管) as an evil hooligan, gained him some fame and cost him a fine of 3,000 yuan (about 400 euro). In 2017, he created another important series of works with Chinese characters for the Internet technology company NetEase, with the goal of expressing the concerns of many young Chinese people. He painted five large-scale brightly coloured murals in three different Chinese cities (Beijing, Shanghai and Canton), in which he posed, in very personally styled Chinese characters, some critical questions for today’s youth (How can we avoid wasting our fleeting youth? What do we have that cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence? What is the best way to die?), together with some of the answers provided by those same youths (Fan 2017). Finally, Camel has created several stickers,12Sticker art (tiezhi 贴纸) – A form of tagging through computer-printed stickers that may contain only the writer’s signature and/or logo or be more elaborate, including small fonts and decorations. Sticker art is quick to execute, cheap, and easy to disseminate, and is considered a sub-category of graffiti art, although some writers believe that this type of art is only for those who are afraid of using markers or spray cans. something quite unusual among Chinese writers, in which he reproduces his style and puppets.

The Tuns crew (tunshi tuya tuandui 吞噬涂鸦团队), founded in 2013, is the first all-women crew in Beijing13This can be read on their official website, while their ZCool page states that the Tuns crew was founded in 2014 and consists of Zhao, Mage, Fasto, Snake, Zstar and Joke. Consequently, according to this composition, it would not be all-female crew.. Its Chinese name Tunshi 吞噬 – from which the term Tuns comes – means phagocytise, and is intended to express the group’ aspiration: to “devour the city” with its pervasive writings. The main exponents of this mission are Zhao, Fatso and Mage, who are devoted both to bombing and to the creation of elaborate pieces containing their tag or the name of the group. They are well versed in the use of both Latin letters and Chinese characters, and in a variety of styles, from bubble to wildstyle14Wildstyle (kuangye fengge 狂野风格) – A complex composition of letters assembled to give a unique shape and dynamic to the piece. In this style, the letters are distorted and superimposed, and sometimes enriched with three-dimensional arrows, tribals, pikes, puppets and other decorative elements that give an idea of movement and confusion. This style can be straight or soft: the first is symmetrical, and the arrows forming the letters draw sharp angles; the second is asymmetrical, and the angles are replaced by curved arrows with rounded points. To increase the perception of depth, in addition to inserting junctions between characters, the entire word structure can be turned into a three-dimensional element. This complicated construction of interlocking letters is considered one of the hardest styles to master and the lettering of the pieces done in wildstyle is often completely undecipherable to non-writers.. They have set up a company based in Beijing and Shanghai which, like that of the DNA crew, aims to create graffiti for commercial purposes.

The latest crew founded in Beijing is YDS (acronym for YiDunShun, 顿 顺 “always stealing”). It was founded in May 2016, during Meeting Neighbourhood, the major graffiti festival organised every year by the ABS crew in 798 Art District. The crew is made up of six members, the most active being Giant and Gear. Giant is the youngest; he was only 18 when he joined the crew, and yet he had already been painting graffiti in the city for three years. He discovered graffiti in the United States, where he was sent by his mother to attend elementary school and live with his father. Due to health problems, Giant was forced to return to China, and has since devoted himself first to skateboarding, then to rap (he is a freestyle rapper) and finally to graffiti (Huang 2016). His decision to pick up the spray can was greatly influenced by watching the documentary Style Wars (1983), directed by Tony Silver, which describes the street hip-hop15Hip-hop (xiha 嘻哈) – A cultural movement that emerged predominantly in the Afro-American and Latino communities of the Bronx in New York, in the late 1970s. The four main aspects or elements of hip-hop culture are speech, music, movement and sign: MCing (shuochang 说 唱), or rap music introduced by Afro- Americans (MC is the acronym of Master of Ceremony); Djing (dadie 打 碟), introduced by Jamaicans; graffiti writing (tuya shuxie 涂鸦书写) and breakdance (diban wu 地板舞 o pili wu 霹雳舞), introduced by Puerto Ricans. culture of early 1980s New York (Crayon 2017). This film helped Giant understand that graffiti springs from a form of rebellion against the system and is a product of social marginalisation (Elvita 2017). As he himself stated, the choice of his tag was accidental: “I needed a tag name so I found a book titled Giant and chose that as my name” (Crayon 2017). His Beijing writers of reference and inspiration are Wreck, Sbam and Zato, the most active at the time of his initiation into graffiti art (together with Boers and Gear).

Gear, his fellow crew member, started to write graffiti together with his university colleague Wreck (KTS crew). Besides being a writer, Gear is also a rapper and a break-dancer, as well as an elementary school art teacher: quite a strange, but successful mix. The meaning of his tag, when used as an adjective, is “Excellent! Strong!!” – the exclamation he hopes the sight of his graffiti will provoke (ibid.).

The YDS crew’s work is very similar to that of KTS and consists mostly in bombing the streets of the city, tagging the crew or individual writers using spray cans and creating bubble style, 3D style and wildstyle blockbusters or throw-ups. The style of Sope, another crew member, is interesting for his use of contrasting colours and chaotic, broken, “vibrating” curves that create the effect of decomposition and liquefaction. The purpose of his works, through this constant repetition of curves, is to show the corrupt state of things from a “degradation perspective”. For Sope, the state of decomposition from which his art draws inspiration is the first evolutionary stage of every natural cycle (Elvita 2017).

Local writers and street artists

Interesting Chinese street artists and writers are still active in Beijing, beside the foreign writers and crews discussed so far. Among these, Biskit and Zeit are definitely worth mentioning. Biskit bombs the streets with his tag through quick throw-ups or elaborate pieces, frequently in collaboration with other writers. Zeit started to make graffiti in Australia and mostly carries on his bombing activity in areas destined to be demolished, creating bubble-style throw-ups of his Chinese tag, Shijian 时 间 (Time), which is the translation of the German term zeit. He also uses Latin letters to write his tag, and usually embellishes his pieces by adorning them with Chinese writing. He strongly believes in the use of Chinese writing in graffiti works made in China (Mouna 2017).

Other writers active today in Beijing are Diego, Mask, Viga, 618, Mczs, Qincy and Poste (Dartnell, Yuansheng 2020; BDMG 2019; Bonniger 2018). As for street artists, the most important are Qi Xinghua, Stu, Shuo, Robbb and Ge Yu Lu. Qi Xinghua is regarded as “Beijing’s first 3D street artist” (Crayon 2017) and “China’s most famous practitioner of anamorphic graffiti” (Wang 2016). He is now 40 years old and has painted the largest existing mural in the world, in Canton, entitled Lion’s Gate Canyon (Crayon 2017). He runs his own graffiti studio and has worked on many government commissions. His works always include references to Chinese art and culture (such as dragons and pandas), as his intention is to depict the traditional aesthetics and culture of China (Wang 2016). Stu, on the other hand, is an artist who uses spray cans to create circles within which he inserts Chinese decorative elements. He draws inspiration from the Russian graffiti writer AK (film Crayon 2012).

Shuo and Robbb are the only two stencil artists in China. Shuo, referred to by many as the “Chinese Banksy” (Pan 2017), started out as a graffiti artist and then switched to stencils16Stencil art (mubanhua 模 版 画) – A widely used street art practice that allows shapes, symbols and letters to be reproduced in series by means of a stencil, cut in such a way as to form a physical negative of the image to be created. In short, it is a technique characterised by the use of a pattern cut out on cardboard (the stencil) that can be quickly reproduced on the wall with a spray can., creating extremely ironic works targeting Chinese society. One of the most popular was made in 2014 and depicts President Xi Jinping in front of a long line of people, including writers and street artists, with the inscription “So busy” above his. The stencil expresses hope that the government will officially acknowledge graffiti art and create space for it in the streets, as for all the other demands of the general public. Due to the political content of his works, Shuo has chosen to stay anonymous. A choice also made by Robbb, who creates life-size stencils depicting Beijing citizens, including children, old people, businesspeople and construction workers, made from photographs taken on the streets and painted on the walls of buildings under demolition. Robbb is a rather prolific artist: more than 200 street art17Street art (jietou yishu 街头艺术) – A mass media term that tries to define all the art forms performed in public places, often illegally and using the most diverse techniques. Born from graffiti writing, it has developed and evolved into different practices over time: sticker art, stencil art, poster art, video projections, sculptures, installations and performances. projects bear his name in the city (Lin 2015).

Another interesting street artist is Ge Yu Lu, who graduated in 2017 from the School of Experimental Art of the China Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. In 2013, he hung a sign, replicating the city’s street signs, in a street in Beijing with the three characters of his name, Ge 葛 Yu 宇 Lu 路. Having no other road sign, the street has been called “Ge Yu Lu” for no less than four years, even though it originally had a different name. Following the success of this brilliant street art action, Ge Yu Lu repeated the same experiment in a number of other streets in the capital (Pan 2017).

The development stages of Beijing graffiti

Except for the early experiences of Zhang Dali and Li Qiuqiu (1995-2005), the first real development of graffiti spanned the years from 2005 to 2008, when the first two halls of fame were established in the city (at Renmin University and China-Japan Friendship Hospital), the first crews were formed, and the first foreign writers began to operate and influence the emerging scene.

The period from 2009 to 2013, instead, represented the golden age of graffiti in Beijing. At the time, the city was essentially a blank slate for a small number of crews and writers – either Chinese or foreign – working together, and the countless pieces and tags they painted in different parts of the city would remain for weeks or months before being covered up (Crayon 2017). The halls of fame were multiplying: the most important was on Jingmi Road (Jingmilu 京 密 路), a long highway running north-east of the capital from the city centre to the airport, used for the first time in 2010 by the ABS crew. In 2012, it became the longest hall of fame in Beijing. Thus, Jingmi Road, alongside historical places like the 789 Art District, the Sanlitun neighbourhood, Underground Line 10 from Zhichun Road to Wudaokou, the Gulou area in the city centre and Tainchun Road, northwest of Haidian District, were covered with graffiti (Yau 2018; Huang 2016).

Starting from the end of 2014, however, things have changed: the development of graffiti art has significantly slowed down because Beijing has become increasingly expensive and, since the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in 2014, there has been a huge effort by the government to remove all the graffiti in the city (Crayon 2017). Moreover, in recent times, intensification of the government initiative Embellishing Beijing is promoting continuous buffing – a process to remove illegal graffiti18Buff or buffing system (qinchu tuya 书法涂鸦) – The removal of illegal graffiti, but also the act of writers when they cover other artists’ tags with their own, or with any other sign. – by urban inspectors, who incessantly cover up graffiti with grey paint (Bonniger 2018, p. 25). Today, the graffiti scene in Beijing is quite limited: only a handful of graffiti crews are still active, generally making graffiti for commercial purposes (like the ABS, DNA and Tuns crew), and the total number of active writers is below one hundred (the exact number is actually unknown). According to Zeit, in 2017 “there were 70-80 graffiti writers in Beijing, only 30 of whom were writing regularly” (Mouna 2017); for Giant, the writers were only 30, of whom 15 were active (Crayon 2017). Andc of the ABS crew is even more pessimistic, stating that less than ten writers were active in Beijing in 2018 (Yau 2018).

Whatever the number, what matters are the pieces, and some of them, be they old or new, are really worth exploring and delving into, particularly with regard to three crews: the Beijing Penzi, the Kwanyin Clan and the ABS crew, which embody the entire history of Beijing graffiti and have opened up new possibilities for the development of graffiti in China.

The first crew in Beijing: the BJPZ

The Beijing Penzi (BJPZ) was the first crew established in the city of Beijing. It was founded in 2006 by Li Qiuqiu (a.k.a. 0528), More (a.k.a. Mo), Soos and Als (from France), and was joined, two years later, by Zak, Quer and Corw (Valjakka 2016, p. 361).

If truth be told, the date of their foundation is not entirely certain: in one interview, Li Qiuqiu states that it was around 2005, in another it was 2006 (ivi, p. 369), and on one of their blogs they mention February 2007. This is due to the informal nature with which the crew was formed: they are a group of friends who met almost by chance and share a passion for graffiti and (in several cases) skateboarding, which was the reason for their collaboration. 41-year-old More, whose real name is Wang Mo, recounts that he met Li Qiuqiu, the crew’s veteran, through skateboarding, and that the Beijing Penzi crew was born out of their desire to do something together (film Crayon 2012). Zak, whose real name is Zhang Lei, says that the idea to join the crew came after meeting More at his friend’s Soos’ birthday party. Only later did he have the opportunity to get in touch and hang out with Li Qiuqiu. In short, the foundation of this crew springs from a series of fortuitous and fortunate coincidences.

Beijing Penzi is an all-round crew. As authors of both elaborate pieces and night-time bombing (which they love the most), the crew members collaborate with famous brands, and also create socially motivated works. They use both the Latin alphabet and Chinese characters in their large-scale works as well as in their tags or lettering on the side of their pieces, and all three Chinese co-founders of the crew (0528, Soos and More) write in both Latin letters and Chinese characters.

Moreover, many figures animate the pieces of these writers, not only the large works but also the quick acts of street bombing, always with a keen eye on bringing out their Chinese cultural background. Still, the presence of the French artist Als proves the internationality and openness of the crew. Als undoubtedly influenced the development and evolution of the style of the entire group with his western background.

In the words of Li Qiuqiu, the name Beijing Penzi 北京喷子, which means “Beijing writers”, was chosen because the term penzi – literally meaning “sprayer, atomizer” and, by extension, “writer” – is used in the Beijing dialect to refer to a garrulous person, and is also the name of a firearm. These two meanings tell us a lot about why the crew was created and what its programmatic aim is. As a matter of fact, according to Li Qiuqiu “[…] We would often have fun bombing together with friends, and so we decided to start our own crew” (interview, 2016).

The idea behind the crew is therefore to reproduce a loquacious expressiveness that floods the audience of passers-by with a thousand words, using the force of a gunshot, but replacing bullets with written messages. What unites the members of the group is the pleasant sense of fulfilment that bombing gives them.

The name of the crew also reveals their background and other purposes that hold them together:

It’s not difficult to understand, from the name of our crew, that we come from the streets. We grew up immersed in the underground culture and we want to carry it forward and promote it. We wish to change the perception of graffiti art and make sure that graffiti is no longer seen as scribbles on the walls but can be accepted and appreciated by everyone. […] Our aim is to make graffiti in as Chinese a style as possible. All over the world graffiti is made using the English alphabet, but ours is not. In our works, we want to represent traditional architecture, the faces of Chinese people […] and Chinese writing, which is unique in the world. We don’t care what others may think of us, this is what we want to keep doing. That’s what graffiti is for us: we “play” with our culture. After all, we are “the Beijing writers” (Beijing penzi) and our background comes from the city most steeped in culture in all China. (Ibid.)

Therefore, the goal of their art is to develop a style that mirrors their Chinese origins (Valjakka 2016, p. 361). Indeed, in their works we find pieces in Chinese characters, Chinese writing and figurative elements that constantly recall the world of “China”.

In memory of the Sichuan earthquake victims

The Beijing Penzi’s 2008 work entitled R.I.P. 512 Sichuan Earthquake (Pic. 4) is representative of their idea of graffiti art. It was created on one of the outer fencing walls of Renmin University, one of the most important halls of fame in Beijing, by Soos, 0528 and More, to commemorate the victims of the devastating earthquake which occurred in the Sichuan region (north-western China) on 12 May 2008, causing around 70,000 deaths.

The acronym R.I.P. in the title of the work means “Rest in Peace”, a farewell from the crew to those who died in the tragedy. The work is composed of a portion with Chinese characters on the left, in which a chengyu (a four-character idiomatic phrase) reads Zhongzhichengcheng 众支(志)成城 (unity is strength). This is an incitement not to be discouraged even in the darkest moments, but to work together to face the immense catastrophe and find the strength to recover.

The four characters composing the chengyu fade from red to yellow on a black background, and their style resembles the running or semi-cursive script (xingshu 行 书 )19The running or semi-cursive script (xingshu) is one of the five fundamental styles of the Chinese art of calligraphy, along with regular script (kaishu 楷书), seal script (zhuanshu 篆书), clerical script (lishu 隶书) and cursive script (caoshu 草书). used in Chinese calligraphy, in which the character strokes are joined together by a single quick stenographic stroke. Its thickness varies constantly, its shapes are rounded, and the beginnings of lines are evident and allow the public to mentally retrace the agitated rhythm of this spray “brushstroke”. Altogether it reproduces the upheaval and brutality of the event. The gestures and poses of the figures portrayed next to the written portion echo the agitation of such moments. To the immediate left, three rescuers from the National Rescue Team, wearing red jackets and helmets, work tirelessly to remove the rubble with their bare hands, trying to save a little girl from the wreckage. The expression on the child’s face is one of terror and all around her is death and despair. By her side, there is a hooded young man with a blurred face trying to rescue another crying child, holding him steadily in his arms. Next to him there is a masked nurse, whose face is unrecognizable, calling for reinforcements with her arm raised. They are all symbols of the kind of humanity that, in the midst of so much despair, rolled up its sleeves to help those in need, and represent the unity of purpose and aid20In this chengyu the character zhi 志(will, aspiration) was replaced by the homophone zhi 支 (to support, sustain, bear) precisely to emphasise the juxtaposition of intent and help. proclaimed by the slogan in characters.

The 3D style number 512 completes the work and stands for the date of the catastrophe, which occurred on the 12th of May. The fill-in colour is red, like the blood that was spilled, while the black depth represents the darkness of the catastrophe, and the yellow outline21Outline (lunkuoxian 轮廓线) – The letter outline, the contour line of the piece that defines and shapes its structure: the outline put on the wall and then filled, or the final outline done around the piece to finish it. Can also refer to the drawing done in a piece book (see Black book) in preparation for doing the actual piece (see Sketch). is a longed for glimmer of light highlighting the importance of the number. At the top of the work there are the artists’ signatures: from left to right we find the names BJPZ Crew in blue, followed by SOOS in black, 0528 in red, and MORE in yellow. On the left side, there is one last inscription on the protruding edge of the wall: Jinian Sichuan 纪念四川 (Commemorate Sichuan). The highly graphic cursive style with which Soos created this element, repeated in the penzi 喷 子 (writer) characters situated vertically below it, recalls the zigzagging of the seismograph waves reproduced to the side, and stands as a reminder of the earthquake.

Underground Basketball

In addition to pieces with a strong social content, Beijing Penzi has created several works on commission. As Li Qiuqiu stated, the crew has collaborated with various brands, like Tiger Beer (part of Heineken Pacific Asia), Lee Jeans, Casio G-Shok (a wristwatch brand), Adidas, Nike, Panasonic and Haier (a Chinese home appliance company). We should also remember that this crew had a commercial orientation even before it was founded: as early as 2001, Li Qiuqiu and his friends created a brand called Shehui 社 会 (Society) linked to the world of skateboarding, with the purpose of promoting events, activities and products connected with spreading this sport in China along with its related cultural industry22The Shehui often collaborates with brands related to hip-hop, street culture and graffiti. The company organises independent concerts, promotes hip-hop music, designs skateboards, has recorded several music albums on skateboard culture in China and designs hip-hop themed clothing, CDs, billboards and other merchandise. Over time, it has become central to China’s underground culture and its related brands: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ndjrivhNpMFqG9DzEOBFpg (last accessed in February 2024). . A few years later, together with the other members of the crew, Li Qiuqiu opened a design studio in Caochangdi – one of the most important art districts in the capital – where he could sell his art, write graffiti on commission, and keep decorating skateboards and other similar objects (Feola 2013)23The studio is no longer active. However, Li Qiuqiu and other members of the crew have opened their own private studios where they continue to create graffiti for commercial purposes. .

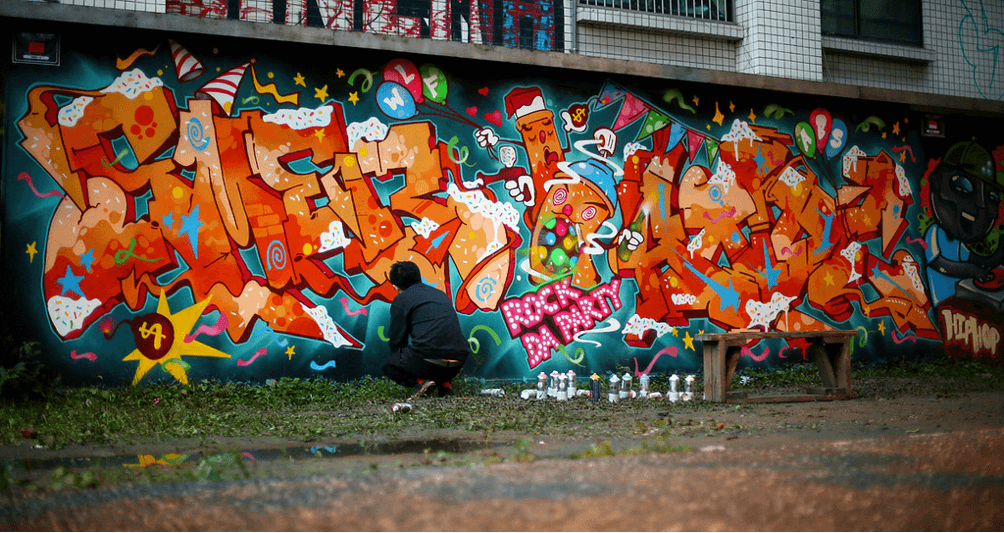

The most famous among the crew’s commercial pieces was the one created in 2007 for Nike (Pic. 1).

At the time of its creation, it was the tallest graffiti piece in China: 10 metres high and 3.15 metres wide24The record was surpassed in 2008 by a Kwanyin Clan work on a 20m high tower. ! It took Soos, 0528 and More two days to complete, and they only employed spray cans for its creation. As in the previous piece, here we find an inscription in Chinese characters, together with a figure with Chinese somatic features and traditional Chinese decorative architectural elements. The work is thus close to a manifesto of the search for “Chineseness” that the crew’s works strive for. The inscription in Chinese characters can be found in the top section of the piece and stands as its title: Wo de lanqiu you jietou dazao 我的篮球由街头打造 (My way of playing basketball is born in the street). It recalls the underground street culture of New York’s inner city and of Chinese cities, where playing basketball is a way to hang out with friends. The inscription sets out to connect the place where graffiti art was born, the USA, to the place where it is now developing, China, while obviously referencing the sport that is the subject of the commercial advertising requested by Nike. The characters are written in 3D style, the fill-in colour is red with beige inlays, decorations and underlines, and the outline is white with dark green depths. This triumph of colours and decorations underlines the sense of light-heartedness with which the piece is imbued. The writing style is rounded and playful, calling to mind the idea of leisure associated with the theme of the graffiti. In the lower part of the piece, a puppet represents a basketball player intent on juggling the ball in the street. He is wearing a pair of dark glasses and a cap slung backwards, which make us think of an outdoor game. His hip-hop look seems to bring him very close to the creators of the piece, but the extremely large hands with which he catches the ball, on which the Nike logo is clearly visible, are a good reminder of the purpose of the work and its commissioner. The outdoor setting is also highlighted by the purple background, over which the player stands out. The skyline is an ancient Chinese city with pagoda roofs and a temple in the middle, a distinctive element of the work of 0528. The whole piece is executed in a very captivating cartoon style. The graffiti is framed by a vine full of yellow buds, which is a recurring element in Soos’ works and his second signature. Inside one of these buds, right in the centre of the work, stands the inscription “Nike” and, below it, the three tags of the authors of the piece (0528, Soos and More) and that of BJPZ.

The piece was created on a panel installed on the outside wall of a Yaxin shop selling branded Nike products in China. The shop is located in Dongsi, in the city centre near the Forbidden City, and represents one of the sanctuaries of sportswear in the capital. Right beside the shop stands a KFC (Kentucky Fried Chicken), the American fast-food chain restaurant specialised in fried chicken, which is very popular in China. Although some might disapprove of it, the location chosen by BJPZ is an emblem of the American-style Chinese consumerism typical of our times. Graffiti, born to fight this kind of inequality-generating society, here integrates to perfection with the surroundings, even becoming an unexpected catalyser and promoter of a hyper-consumerist and disengaged society. There appears to be an inherent contradiction; so why? What lies behind the need to make such graffiti?

When the crew is asked why they commit to this kind of commercial activity, they answer that this is the only way to earn money to be reinvested on the streets. The crew uses their earnings to buy spray cans for their favourite activity: bombing the streets of Beijing at night.

Street bombing

The BJPZ tags covered the city for a few years25BJPZ Crew, Beijing graffiti BJPZ CREW BOMBING IN BEIJING 北京喷子涂鸦团队, video, 6’28’’, published on YouTube by More-BJPZ on 14 December 2008: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3aUl90pXX2w, especially the 3.3 underground car park in the Sanlitun neighbourhood, the 798 Art District, the overground Wudakou line, Nanluoguxiang street in the city centre, the Dawang bridge and the Xinjiekou area, as well as some of the main highways connecting the city, more precisely on Third and Fourth Ring Road North and the Third Ring Road West. Besides the traditional tagging-up, the 3D or bubble style throw-ups, and some bubble style blockbusters (mostly with the name Beijing Penzi), the crew members enjoyed playing with puppets or easily recognizable stylised figures in writing their tags (Fig. 4). 0528 draws young boys’ faces with oblong heads and typical Chinese features (Fig. 4, on the right); More, whose tag seems to reproduce a flattened face with a beak and two large ears, adds a fun cone-shaped puppet with two prominent incisors and round ears (Fig. 4, centre); and Soos paints a Xiao R (小R, Young R), a puppet with a flame-shaped head featuring only two dots serving as eyes, tapering hands and feet, and a stout body (Fig. 4, on the left).

This puppet is reminiscent of the shape of a virus whose task seems to be that of infesting the streets. When painted together with More’s puppet, Xiao R is often accompanied by swirls and a beating heart, as a clear reference to the passion bonding these strange characters. The swirls, called xiandao 线 道 , literally “roads of lines” (Llys 2015), are a second recurring feature in Soos’ works. They became his signature style, together with another element he invented, the “jellyfish clouds” (shuimo yiyun 水母意云): little cloud-shaped floral outgrowths arising from the tentacles of a jellyfish. The idea of the jellyfish is echoed in the sinuosity of the stems of these strange pom-pom flowers (see the buds in Pic. 1). The inspiration for the jellyfish clouds comes from the Kongming deng 孔明灯, a type of oil lamp with steam vents invented by one of the greatest strategists of ancient China, Zhuge Liang (181-234), whose public name was Kongming. The jellyfish clouds, together with Chinese writings, faces, and architectures, are meant to enhance a sense of “Chineseness”, often expressed in BJPZ’s works.

Li Qiuqiu, the forerunner of Chinese graffiti

The intense bombing activity that has been a feature of BJPZ since its foundation has decreased over time. After a few years of hard work on the streets, the crew members are now actively working mostly on commission, and only rarely do they have time to create on the streets (Valjakka 2016, p. 361). The reason is that most of them have families, therefore the time on their hands is limited and they need a more stable occupation to provide for their household. For example, Li Qiuqiu is now the father of twins and, therefore, has little time for graffiti, especially those on the streets that fulfilled him the most (Huang 2016). In fact, as he states himself, although the crew is still active, each of its members now has other jobs, making it difficult to create pieces all together (interview, 2021).

Among the various members of the crew, Li Qiuqiu is the only one to have really made graffiti history, not only in Beijing, but in the whole of China. He is considered by many to be “the father of Beijing graffiti” and the leader of the movement. For this reason, he earned the nickname of “old boss” (laoda 老大) (see Video section, film Crayon 2012). Li Qiuqiu was born in 1978 and is now 46 years old, but he started creating graffiti in 1996 (Valjakka 2016, p. 361) when he was only 18. At the beginning he did not write; instead, he depicted simple figures with his spray cans. Around 1999-2000, he started to write his tag 0528, marking his territory around the old city of Beijing (Wang 2016).

Actually, when asked when he started graffitiing, Li Qiuqiu answers: “I believe that everything dates back to my elementary school days; I have loved to paint ever since I was a child, and back then I often used chalk and brushes to draw and write on walls” (interview, 2016).

In short, he was born to be a writer – one who initially, however, lacked a tag. About this choice, Li Qiuqiu recounts: “0528 is a reference to my birthday [the 28th of May]; I chose this tag in the hope that everyone would remember when I was born!” (interview, 2016). This may sound a bit eccentric, but is reminiscent of the numeric tags of the first writers in New York, although those were linked to the street numbers of their homes. By using his birthday as his personal tag, 0528 would later be emulated by a member of another important Beijing crew the TMM crew, whose tag is 525 as a reference to the writer’s date of birth, the 25th of May. Li Qiuqiu thus seems to have set an example even in the choice of tag, but his influence goes further than this.

Li Qiuqiu’s initiation to graffiti art is linked to another of his great passions: skateboarding. Indeed, Li Qiuqiu often went to the Wudaokou neighbourhood to practice with his skateboard together with friends, and this offered him the opportunity to soak up the hip-hop culture (Huang 2016). As we already mentioned, it was thanks to this passion that he met More, and they subsequently came up with the idea to form the BJPZ crew (for More, see ibid.). In 2001, he also founded the Shehui 社 会 (see § Basket underground) brand together with other friends, which is still very active today and for which he continues to work, dealing with graphics and brand dissemination.

Although Li Qiuqiu never disdained the commercial side of graffiti, the main purpose of his art is strongly linked to the old school and the wish to bomb the city with his tags and pieces as an act of denunciation and rebellion, even though his works are actually neither seditious nor subversive. More than 10 years ago, 0528 refused to create Olympics themed graffiti in the 798 Art District, even though commissioned by the government. This was because, as he says, he wanted to feel free to do whatever he wanted, wherever he wanted, never allowing things to be imposed from above (film Crayon 2012)26Furthermore, there was no reimbursement for the canisters, nor compensation for the work done.. Since he sees himself as a free spirit, his “contacts” with the police have not been at all rare (Wang 2016)27An interview with Liu Qiuqiu reported by Wang 2016 reads: “Numerous times, he was stopped by the city’s chengguan [city inspectors], fined, and ordered to paint over his tags.”. As he recalls, the first encounter was during high school, when he was making graffiti near the Temple of Heaven, one of the city’s renowned monuments. The policemen confiscated his ID card, which his father demanded back the next day, provided Li Qiuqiu restored the wall to its original condition before his intervention. His worst experience was in 2010, in Amsterdam, where painting on walls is a crime. He was arrested, held in custody for 24 hours and had to pay a fine of 370 euro to get out of prison, an exorbitant amount for his means! The funniest anecdote happened in 2006 in Tianjin, a big city close to Beijing. On that occasion, the police approached him while he was making graffiti on a government building wall – the Municipality– which was considered utterly unacceptable. They took him to the police station, but here one of the policemen declared he knew and liked his art. He mentioned to his colleagues that the person they had detained was an artist and, through his intervention, Li Qiuqiu was released after 24 hours of custody without even having to pay a fine (film Crayon 2012).

These “encounters” with the police were frequent also for the other crew members. For example, More said that he and other writers happened to be picked up by policemen quite regularly because they mostly bomb at night. For him, the most troubling experience happened while creating graffiti in Shanxi, a region near the municipality of Beijing, where he had to pay a 300 yuan fine (around 40 euro) to be released (ibid.). Zak, on the other hand, was first detained by the police when he was writing his tag with a marker28Marker (makebi 马克笔) – The pen used to paint tags. on an underground carriage door at the Andingmen station in Beijing. As he explains, this was the first of a long series of arrests, and every time the police forced him to cover up his writings. From his own experience, he also learned that during festivities and major city events, detention is more likely because police checks are more frequent (ibid.). Unlike Europe, China has no specific law regulating vandalism on walls, so writers are generally tolerated, and punishments are minimal – usually small fines or an order to cover up their work – although this does not mean going unnoticed by the police. However, as experienced by Li Qiuqiu in Amsterdam, things are very different in the West!

Besides being considered the father of Beijing graffiti, Li Qiuqiu is certainly a pioneer of the development of a “Chinese style”. He was arguably the first to experiment with the use of Chinese characters in his graffiti, or at least his are the first of which we have photographic evidence. Indeed, among the first pictures of pieces with such characters in Beijing are two works by Li Qiuqiu (Pic. 2, Fig. 5). These were captured in 2005 by Liu Yuansheng (a.k.a. Llys), a retired professor with a passion for photography who has been documenting the development of local graffiti art since 2004, going around the city in search of works to take pictures of and share through his official blog.

In the first work (Pic. 2), Li Qiuqiu painted the head of a black man on the left, his tag 0528 in the middle, and the two characters of the brand Shehui 社 会 (Society) on the left. The character depicted is typical of the initial stage of his career, when he used to draw enormous heads of men with half-closed eyes, full lips, a snub nose, sometimes with sunglasses and a bald head or with the features of a man of colour. The style is always caricature-like, and the idea behind these big heads probably comes from the giant profiles used by Zhang Dali in his series Dialogue and Demolition (Fig. 2). Li Qiuqiu himself admits that Zhang Dali was somehow an influence for his art (Valjakka 2016, p. 361), together with other street artists like Banksy, Bonzai, Hobey, Kobra and Chinaman (Li 2016)29In the same interview (Li 2016), Li Qiuqiu affirms that the comics of Otomo Katsuhiro and Kim Jung Gi were further sources of inspiration for his art. On the other hand, his music references are 2pac, Nan, Wu Tang, Bob Marley, Mozart and Paquito (D’Rivera), and he is a fan of the literary works of Wang Shuo, Jin Yong and Gu Long. His family and friends also had a strong influence on his style.. As for the structure of this work, we can see the tag 0528 in the middle, rendered in 3D style with blue and light blue double depths and no fill-in. The tag is stroked by the large hand of the curly-haired character on the left, introducing a sense of continuity between these two elements. The colouring and the sinuous progression of the writing evoke sea waves, and the drips under the number recall an aquatic atmosphere. It is not by chance that the two Chinese characters on the right stand out on a background of blue bubbles, the same colour as the writing: the fill-in is light blue, the outline is white, and the depths are blue. The work was created in Wudaokou, one of the most international and graffiti-rich neighbourhoods in Beijing, on the enclosing walls of a residential area that isolate it from the rest of the neighbourhood, like a ghetto markedly separating the wealthy from the rest of the population. The place was not chosen randomly, but obviously hides an underlying social criticism. The writing style used for the Chinese characters is geometric and reminiscent of “regular script” (kaishu 楷 书), an easily intelligible calligraphic style where each stroke is distinct and discernible.

We can find an evolution of this geometric style in works like Bie feihua 别废话 (No superfluous words, 2006), whose lines reveal the influence of the graphic style used in the tagging-up and of the bubble style used in works like Penzi’er 喷子儿 (2005, Fig. 5).

Compared to Shehui 社会 (Pic. 2) of 2005, in works like Bie feihua or others created slightly later some of the strokes are rounded and appear more fluid-like, without however losing their geometric shape completely. This leads to Li Qiuqiu’s writing style, in which the strokes are sometimes rounded, sometimes orthogonal, in a skilful interplay of delicate balances.

The second piece with Chinese characters from 2005 of which we have photographic evidence is Penzi’er 喷子儿 (Fig. 5). It was created at the 798 Art District, another historically important place for Beijing graffiti. It is composed of three characters, pen zi er 喷子儿, which together mean “writer”. The first two characters are the same used in the crew’s name (penzi), to which the suffix er “儿” – a typical ending of the Beijing slang – is added. This small addition made the authorship of the piece, or at least the writer who created it, unequivocal. The writing style thoroughly differs from the other 2005 work (Pic. 2): this features a very rounded bubble style in which the character strokes are joined together, as in running script (xingshu). 3D style is employed too: the fill-in is a triumph of colours and nuances ranging from blue to green and red, while the depths and outline are black. This mixture of styles, with multicoloured three-dimensional characters written lengthwise30Charactering – Term we have coined to designate the style of characters in writing pieces (see Lettering), or the use of Chinese characters in graffiti., whose strokes are stretched, rounded and stenographic as in running hand script, and in which the thickness of the strokes always varies like in calligraphy, is a very distinctive stylistic feature of Li Qiuqiu’s works. As in Shehui (Pic. 2), the background is a tangle of bubbles, waves are depicted within the characters (in the central section), and the face of a seal (or penguin) appears in the bottom left-hand corner. All elements that, again, are reminiscent of aquatic settings. Thus, through the marine atmosphere, in these first two pieces (Pic. 2 and Fig. 5) Li Qiuqiu seems to disclose a world in which everything – waves, bubbles, architecture, walls, street art – is fluid and fleeting, while also granting a touch of liveliness to the composition, as we occasionally find in his graffiti.

Another important work in which Li Qiuqiu abundantly employs Chinese characters is the one he created in June 2006 in the underground car park of the 3.3 mall, in the Sanlitun neighbourhood (Fig. 6). This piece was part of a work commissioned to 0528 and other famous writers by the owner of the mall, with the purpose of attracting young customers. The project proved so successful that it was repeated in 2011, and some of the graffiti made on that occasion are still standing today (Bonniger 2018, p. 22)31US journalist Lance Crayon, who was sent to report on the event in 2011, was so impressed that he came up with the idea of the first documentary on graffiti in Beijing: Spray Painting Beijing. Graffiti in the Capital of China..

Li Qiuqiu’s piece, which stretches over two different portions of the wall, consists of two puppets, an inscription in Chinese characters, and various other one-liner Chinese and English writings. The first cartoon style puppet depicts a little pig with a helmet, her fingers raised in a sign of victory. She is portrayed wearing a summer dress with the character chi 吃 (to eat) at the centre. Next to her is the large inscription Wan 65 jiu shi xintiao 玩 65 就是心跳 (Playing 65 is heart-stopping). The number 65 refers to one of the biggest online videogame platforms in China and expresses the intent to target a young audience. The 3D style is achieved with striped red and light blue fill-ins, and purple depths and outline. The charactering style is reminiscent of running script with many strokes joined in a single “brushstroke”. The strokes are always sinuous and rounded, like marshmallows. This style is the upgrade of the artist’s early bubble style and will often be used by Li Qiuqiu in other pieces (Fig. 5).

The expression in characters Wan 65 jiu shi xintiao 玩65就是心跳 can also be found on the second puppet’s cap. Here, the calligraphic style is similar, but the strokes are simple black lines obtained by means of a single spray of paint. The same captivating graphic writing style also occurs in the word “Fuck” on the puppet’s cap, in the characters kaishi 开始 (lit. to start) placed in the direction of his finger, and in the tag 0528 below his hand (the last two elements are also found in the other section of the work). The dots with which the lines end and the decorations that highlight them are typical of the style adopted here. This type of writing is also found in many of Li Qiuqiu’s later works, particularly in his tags.

The second puppet is a writer, or in any case a young man imbued with hip-hop culture, as is clear from his clothes (cap and large T-shirt), his grumpy expression and the insulting word on his cap. He has the features of 0528’s puppets (large face, almond-shaped eyes, full lips and snub nose) and the somatic traits are those of a young Chinese man. The puppet’s colours are unrealistic (purple skin, yellow mouth and eyes, red shading), but recall the colours used in the other section of the piece and in the arrows in the background. The choice of the puppet is certainly linked to the work’s target audience and to the intention of offering an alter ego of the non-conformist soul of the new generation, with which young people can identify.

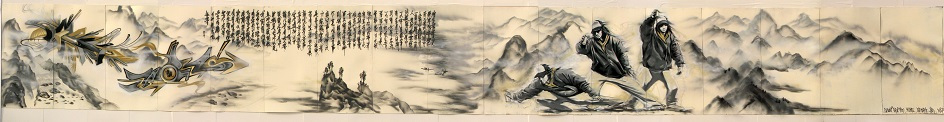

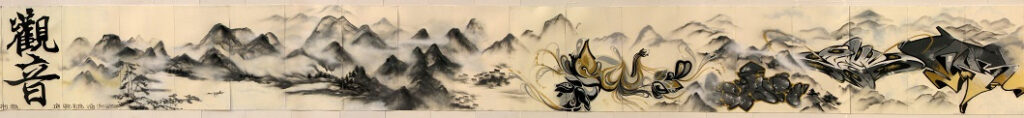

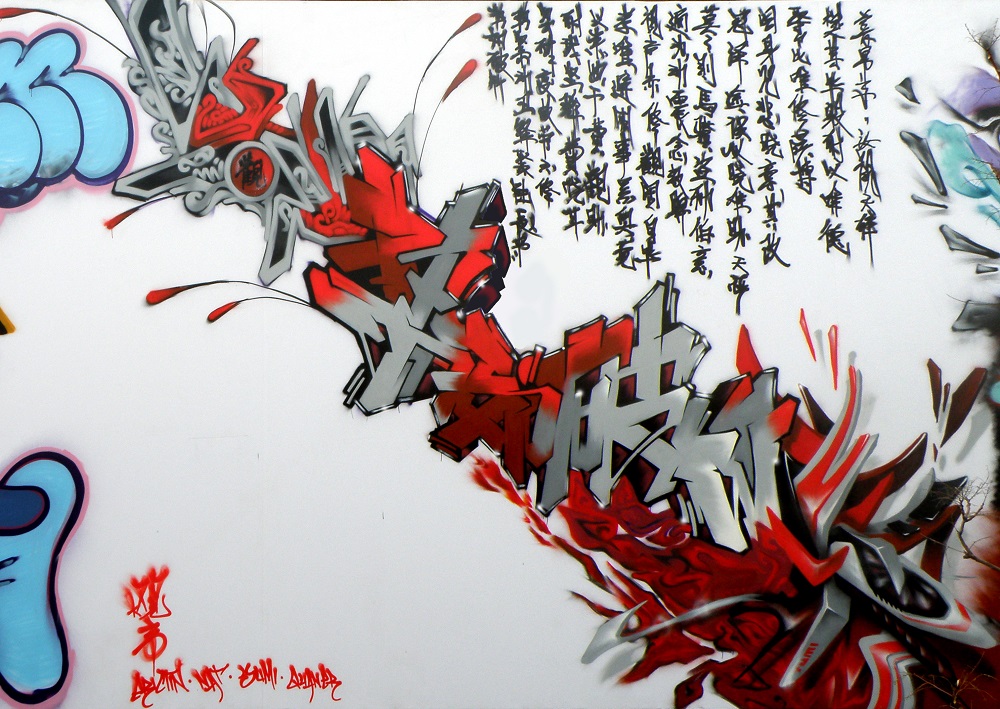

Even though it is a commercial piece, this graffiti is of great importance for the stylistic development of Li Qiuqiu’s art because it displays writing styles and characters that will become representative of his future production: the writing style of the characters will be found in other similar works done on the streets, the puppet of the young writer is a clear evolution of the balding heads and faces depicted before, and the single black line writing style will become a signature of his later works. This writing style will also feature in a recurring expression used in his graffiti, Bie feihua 别 废 话 (No superfluous words), generally used in his bombing activity.