2. Defending Rome

One of the more remarkable documents found in the Nicholas Brown papers at the John Hay library is a May 3 message to Brown, signed by the Triumvirate ruling the Roman Republic: Giuseppe Mazzini, Carlo Armellini, and Aurelio Saffi. That they found the time to write to Brown only three days after the French attack offers one sign of the importance they attached to his support. They wrote the note in French: “We are profoundly touched, Sir, by the sentiments you have expressed for the Roman Republic and for the efforts you have made to get your government to recognize it. We expected no less of a man whose great intelligence is equaled by his noble character.” For the black sheep of the Brown family this must have been heady stuff.1See Document #3 in the section “SELECTED DOCUMENTS FROM THE NICHOLAS BROWN PAPERS, JOHN HAY LIBRARY, BROWN UNIVERSITY”: “Nous avons été profondément touchés, Monsieur, des sentimens [sic] que vous exprimez pour la république romaine, et des efforts que vous avez faits pour obtenir que votre gouvernement se décidât à la reconnaître. Nous n’attendions pas moins d’un homme, chez qui la haute intelligence égale le noble caractère” (Mazzini, Armellini, and Saffi to Brown, 3 Mai 1849, in Nicholas Brown papers).

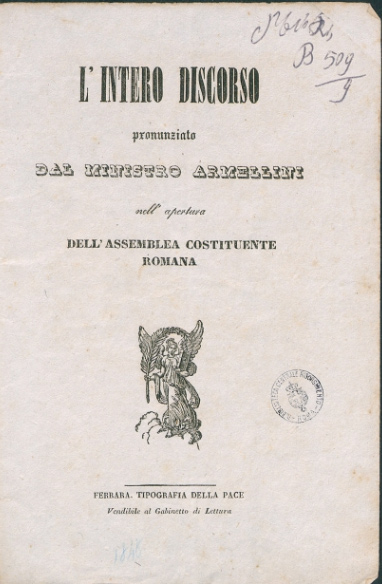

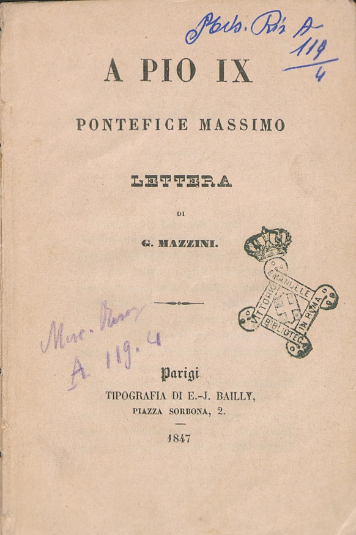

Mazzini was more of a prophet than a politician, but with the French army now camped nearby awaiting reinforcements, the Neapolitan and Spanish armies marching north toward Rome, and the fearsome Austrian army readying its march south on the Papal States, he realized that only one thing could save his Roman Republic from speedy defeat. The French National Assembly had never authorized a war to return the pope to power.2For a flavor of the heated debate in the French Assembly on receiving news of what had happened in Paris on April 30 see Assemblée nationale 1849, pp. 469-490, Séance du 7 mai.

If, prompted by popular protests in Paris, the Assembly would vote out the government, the French army’s mission might be transformed. Instead of coming to put an end to the republic, it might use its firepower to protect it from the autocratic foreign governments intent on destroying it.

One of the documents in the John Hay collection offers precious insight into this mindset. On May 10 Alfred Lowe, the vice consul in Civitavecchia, sent Nicholas Brown a letter advising him of the latest French troop reinforcements to arrive there. Yet he added a further note:

There is a rumour current here of the greatest excitement prevailing in Paris consequent upon the attempted forced entry of the French Troops at Rome: and fears, or otherwise are entertained that another Revolution must take place. 3Consolato degli Stati Uniti, Civita Vecchia 10th May 1849, to Nicholas Brown Esqu., Consul General of the United States of America, Rome, in the Nicholas Brown papers. In his May 4 report to Brown, Lowe told of the continuing arrival of French ships of war, disgorging troops who were then proceeding to reinforce those already near Rome. The May 4 letter also mentions the passing on the night of May 2 of the U.S. steam frigate, Princeton, having on board a deputation from the new government in Florence, on their way to meet with the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had earlier fled to Gaeta himself.

That the great prophet of Italian unification, and leader of the Roman Republic, Giuseppe Mazzini, came to rely on Nicholas Brown in these fateful days is clear from various documents found in the John Hay collection. A letter Mazzini wrote on May 11 begins: “You have shown yourself so favourable to our cause, that I do not hesitate to ask you if you can render us a great service by granting two American passports …” He went on to explain that he needed the passports for envoys tasked with an important mission abroad and carrying a large sum of money.4Intriguingly, as a postscript to this request, Mazzini asks “Can we rely upon the information given by the Prince of Canino concerning England?” The Prince of Canino, Charles Bonaparte, was then presiding over Rome’s Constituent Assembly, while his cousin Louis Napoleon, president of the French Republic was responsible for the army that had just attacked Rome.

Three days later, we now know thanks to the John Hay manuscript collection, Mazzini again asked for Brown’s help, this time getting an American passport for his friend Adriano Lemmi, a key figure and fund-raiser for Italian Unification and later head of Italian Masonry.5See Document #4 in the section “SELECTED DOCUMENTS FROM THE NICHOLAS BROWN PAPERS, JOHN HAY LIBRARY, BROWN UNIVERSITY”: Mazzini to Brown, May 14, 1849, Nicholas Brown papers. On Lemmi (1822-1906), see Conti (2005). Throughout the month, Brown received fresh reports from Lowe in Civitavecchia, telling of the size of the various landings of French troops and weapons. Lowe’s May 15 report also noted the arrival the previous day of the French ship, the Pomona, having on board, in addition to 390 men and 36 guns, recounted Lowe, the new French emissary, Ferdinand de Lesseps. Lesseps, appointed at the insistence of the enraged French Assembly following the initial French assault on Rome, was about to embark on his ill-fated attempt to bring a peaceful end to the standoff there.6Lowe to Brown, May 15, 1849. Lowe reported further French troop arrivals in a letter of May 22. Both are found in the Nicholas Brown papers.

As an aside, the John Hay documents contain material sent to the Browns by the famed American journalist Margaret Fuller, who was experiencing her own personal drama in Rome while sending in dispatches on the Roman revolution to the American press. She had recently given birth secretly, having fallen in love with—and perhaps married to—an Italian who was fighting in the republican forces. In her May 27 newspaper dispatch she praised Brown, describing how the noblewoman Cristina Belgiojoso—perhaps the most prominent woman in the Italian Risorgimento—had recently gone around Rome soliciting funds to support her work in charge of medical care for wounded soldiers: “the voluntary contributions were generous. … I am proud to say, the Americans in Rome gave $250, of which a handsome portion came from Mr. Brown, the Consul.”7Fuller 1991, p. 282. In the John Hay archive we find a note written by Margaret Fuller to Mrs. Brown, who had extended a dinner invitation to her, perhaps that same month:

Dear Madam,

A friend, who has a child very ill, expects me to stay with her this night. It is also difficult for me to make visits in the evening as I am alone and have no manservant. I shall see you again some day, when I can return at sunset.8The Fuller letter to Mrs. Brown, in the Nicholas Brown papers, is dated simply “Tuesday”.

Meanwhile, Nicholas Brown continued his stream of enthusiastic reports to Washington about the virtues of the Roman Republic. “The warmest feelings of humanity,” he wrote on May 19, animate the [Roman] population, after the battle [in which the French were repelled on April 30]. The French wounded & other prisoners are treated with the utmost kindness. … During this terrible crisis, public order remained undisturbed. … Meanwhile, the Constituent Assembly … has steadily proceeded in its well-pondered and judicious career of reform.”9Brown to Clayton, Rome, May 19th, 1849 (Stock 1945, pp. 173-175).

On June 2, with Rome under siege, Brown received a laissez passer from the chargé d’affaires of the French embassy in Rome to permit him, his wife, and their two children, along with the family doctor, to travel “in his own carriage and with his own horses” to the home of the American vice consul in Civitavecchia.10M. de Gerando, Chancelier, chargé des affaires de la République Française, à Nicholas Brown, 6 juin 1849, Nicholas Brown papers. It seems unlikely that he ever made the trip, as late that same night, the final French assault on Rome began.

Despite the heavy bombardment of the walls of Rome by the greatly reinforced French troops, and the death and maiming of many of Rome’s defenders, the city’s defenses initially held. Lesseps, who had at the beginning of June come to a peaceful agreement with Mazzini and the republic’s leaders, had been recalled and repudiated by Louis Napoleon. On June 11, eight days after the new French assault on Rome began, Lowe informed Brown of the arrival at Civitavecchia of Francisque Corcelle, personal envoy of the new French foreign minister, Alexis de Tocqueville, along with Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, secretary to the French embassy. The two men left almost immediately, Lowe reported, for the French military headquarters outside Rome. He added: “but as to what instructions given them, or powers they are endowed with, we here are perfectly ignorant. … Tomorrow it is said that an attack will be made by the French, that is to say they will make a Breach with their heavy artillery and attempt an entry by that, unless the abovenamed gentlemen bring counter orders, but on this score I fear there is little to hope for.”11Lowe to Brown, June 11, 1849, Nicholas Brown papers.

Several days later, a demonstration in Paris, viewed by the French government as an attempted uprising, protesting the war on the Roman Republic, was quickly repressed. It was now only a matter of time until the old wall surrounding the Eternal City would give way to the French bombardment. As it intensified, a group of foreign consuls and chargés d’affaires in Rome decided to organize a joint protest, addressed to General Oudinot. Six of them sent a draft of the protest to Brown on June 24 and called on him, as the representative of “a great and civil nation” to join in. Charles Kolb, the consul of Wurttemburg, sent a note to Brown, in French, telling Brown that the consuls were meeting in his home that day and would then take their petition to Oudinot at the French headquarters outside the city walls. The statement decried the continual nightly bombardment which was raining terror on the city and damaging priceless historical buildings and monuments. Brown quickly signed on.12The letter from the six consuls is dated June 24, while the letter from Kolb to Brown is undated. Both are found in the Nicholas Brown papers. Although Brown signed the protest, it is unclear if he went with the delegation to meet with Oudinot. Oudinot was unmoved. He acknowledged the bombardment of the city and the damage it was causing, but told the consuls that the fault lay solely with the Romans who stubbornly refused to surrender peacefully. The bombardment of Rome continued.13Discussed in Kertzer 2018, pp. 243-244. Curiously, the Nicholas Brown papers also include a letter by Daniele Manin, hero of the Venetian revolt against the Austrians, and leader of the only other yet to be conquered revolution still holding out against restoration. Along with his calling card, Manin wrote Brown to say that he thought it was his duty to sign the protest of the foreign diplomats to Oudinot.

On June 29, with the wall breached, Nicholas Brown submitted his letter of resignation to the U.S. secretary of state. He claimed that he had planned to resign following the election of Zachary Taylor several months earlier, but had postponed it due to the dramatic events in Rome. It appears though that Brown was forced out by the U.S. government, unhappy at his flouting of instructions not to appear as a partisan of either side in the Roman conflict. Indeed, his successor had already been appointed a month before he sent his resignation.14Brown’s letter of resignation can be found in Stock 1945, p. 178; Fiorentino (2000, pp. 89-90) also refers to Brown being forced out. The new American consul, William Sanders, would arrive in Rome on August 20.15A number of Brown family histories refer to Nicholas Brown’s term as American consul in Rome as lasting into the 1850s. These are in error. Among the U.S. government instructions that Brown did not follow were the last ones he received, telling him to give Sanders, his successor, all the archives and property of the consulate. Had he done so, the U.S. government and not Brown University would have ended up with his papers from Rome.