Introduction

Adriana Iezzi

China is a vast country, the extension of which amounts to 30 times the Italian territory, making it the third largest area in the world after Russia and Canada. With 1,400,000 inhabitants, it is also the world’s most populous country. This handful of figures shows how complex and dispersive China, or rather the People’s Republic of China (mainland China), is: we are talking about an entire continent! Analysing any socio-cultural phenomenon with respect to so enormous an area with such a diverse population – composed of 56 different ethnicities – is, therefore, a titanic effort.

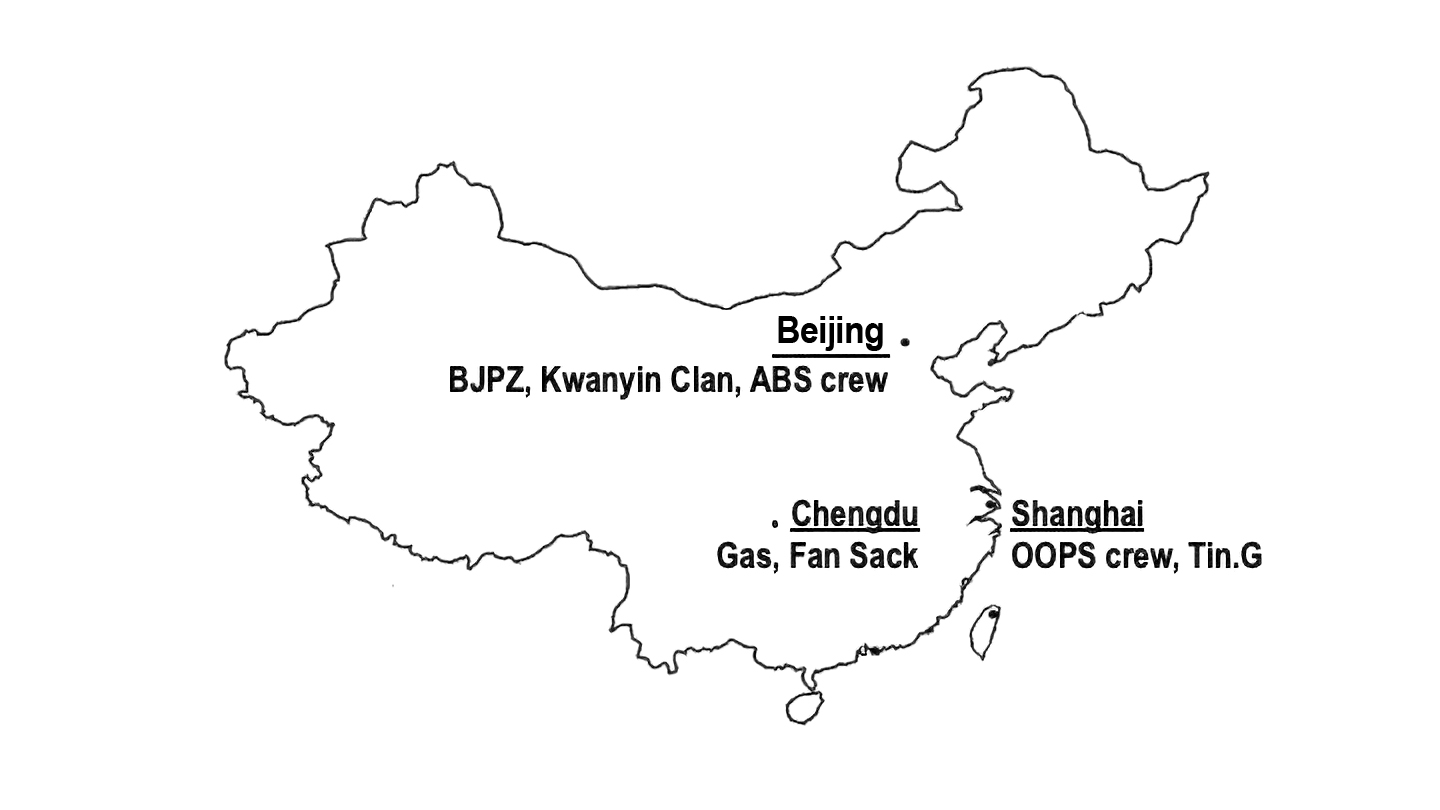

This book about graffiti in China focuses on three cities – Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu – and some of their most influential crews1Crew (tuandui 团队) – In hip hop culture, a circle of people collaborating on artistic or cultural projects, e.g., a group of writers or dancers. In graffiti writing, a crew is an organised group of writers who paint together to create pieces. They are usually friends, meaning they share mutual esteem and respect. A writer may belong to more than one crew over time, or even at the same time. The name of a crew is normally an acronym of two or three letters, possibly having multiple meanings. Like tags, crews’ names are often written on the side of the piece, or they form the very core of the piece, with the name of the crew members dotted all around. and writers2Writer (tuyazhe 涂鸦者 / penzi 喷子 / tuya yishujia 涂鸦艺术家 / xieziren 写字人) – An artist who executes graffiti mainly based on lettering. (Fig. 1). Rather than provide insight into the current Chinese graffiti scenario, which would take at least a dozen books, it aims to offer a glimpse of the phenomenon, of which little is known, and a stimulating analysis of modern China and its structure, which is considerably distant from the western world, and therefore all the more fascinating.

The leading artists of Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu

The choice of the cities of Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu was not made randomly, but on three grounds: the first is geographical, the second strategic, and the third purely personal.

With regard to the geographical motive, Beijing is located in the north of the country, Shanghai in the south, and Chengdu in the centre (Fig. 1). Therefore, each of them represents the core of their respective areas, and together they essentially represent the entire Chinese territory.

Strategically, they feature three divergent and peculiar ways of spreading graffiti, each very different from the other. Beijing is the capital of China as well as its political and administrative core; the authorities have a strong, sometimes even repressive presence here, and yet it is a city with a lively artistic scene and the site of the country’s first graffiti. Shanghai is China’s economic and financial core, a “cosmopolitan” city, possibly the most western in the country, with a huge number of foreigners, and its international and commercial nature is reflected in its graffiti art. Chengdu, on the other hand, is a marginal centre where, however, graffiti has had space to spread considerably, epitomising the importance of minor cities in the diffusion of this art form in China.

The third and perhaps predominant reason that guided our choice is that these are the cities in which we conducted our research. In these cities we had the chance to meet the artists and to see first-hand how the development of graffiti progressed.

The crews and writers presented are the result of our direct experience, and thus cannot be considered exhaustively representative of the cities’ graffiti scene. They are the artists that we managed to interview personally, in order to provide fist-hand testimonies and recount through their words what we saw on the walls and/or heard about from secondary sources. Of course, we didn’t choose them arbitrarily: we sought to reach the artists who embody the graffiti phenomenon of their respective city and, together, give as diverse an overview as possible of graffiti in China.

Reading guidelines

The structure of this book is simple and intuitive: the first two chapters give a general framework of the phenomenon. Chapter I, by Marta R. Bisceglia, is about the rise of graffiti in the West, while chapter II, by Adriana Iezzi, is dedicated to its spread in China. The other three are macro-chapters, respectively about Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu. Their openings outline the cities’ hallmarks, as well as the diffusion of graffiti in the area. These parts outline the contexts in which the artists analysed in the following paragraphs can be properly placed.

For Beijing (see Ch. III by Adriana Iezzi), we examined three of the preeminent crews that have made the history of graffiti in the capital: the Beijing Penzi, the Kwanyin Clan and the ABS crew.

The Beijing Penzi is the first crew established in the city, and its top representative, Li Qiuqiu (a.k.a. 0528), is the forerunner of Beijing graffiti, as well as the first acknowledged graffiti writer in China.

The Kwanyin Clan is another of the first crews formed in Beijing and the one that above all has searched for a Chinese style rooted in traditional culture (they make use of characters and add references to calligraphy, traditional painting and literature to their pieces). EricTin, whom we interviewed, is one of its founders, as well as the artist that most drives the group in this direction.

Very active to this day, the ABS is a long-standing crew in Beijing and the most successful. They were the first to open a graffiti store and make graffiti art their actual job, through collaborations with major brands. They were also the first to travel to Europe and work with foreign writers, giving the group a strong international flavour. We conducted several interviews with Andc, the social soul of the group, who contributed to opening the crew up to the world.

For Shanghai (see Ch. IV by Marta R. Bisceglia), we chose the city’s first and foremost crew, the Oops Crew, which has succeeded in combining Chinese features with a fresh modern style. Moreover, we interviewed the female writer Tin.G who founded the first all-women Chinese crew, the China Graffiti Girls (CGG). Her stile has evolved from simple writing to stickers3Sticker art (tiezhi 贴纸) – A form of tagging through computer-printed stickers that may contain only the writer’s signature and/or logo or be more elaborate, including small fonts and decorations. Sticker art is quick to execute, cheap, and easy to disseminate, and is considered a sub-category of graffiti art, although some writers believe that this type of art is only for those who are afraid of using markers or spray cans. and finally to elaborate pieces with puppets4Puppet (tu’an 图 案) – Figurative elements alongside the graffiti. These may be human figures, animal-like monsters, or comic or cartoon characters (see Character). and an “ultrafeminine” aesthetic.

For Chenghu (see Ch. V by Martina Merenda), we present two very different writers: the forerunner Gas, who paints extremely intricate Chinese characters and elements that point to the “Chineseness” of his pieces; and Fan Sack, a Chengdu writer who moved to Paris and whose art has gone from old style writing to painted pieces of Buddhist inspiration, while never abandoning his native street world.

The book closes with a graffiti-themed terminology glossary (by Marta R. Bisceglia), where the reader can find in-depth descriptions of technical terms (such as writer, crew, tag, wildstyle5Wildstyle (kuangye fengge 狂野风格) – A complex composition of letters assembled to give a unique shape and dynamic to the piece. In this style, the letters are distorted and superimposed, and sometimes enriched with three- dimensional arrows, tribals, pikes, puppets and other decorative elements that give an idea of movement and confusion. This style can be straight or soft: the first is symmetrical, and the arrows forming the letters draw sharp angles; the second is asymmetrical, and the angles are replaced by curved arrows with rounded points. To increase the perception of depth, in addition to inserting junctions between characters, the entire word structure can be turned into a three-dimensional element. This complicated construction of interlocking letters is considered one of the hardest styles to master and the lettering of the pieces done in wildstyle is often completely undecipherable to non-writers., etc.) alongside their Chinese translation. As a result, such terms are explained only once, when they first appear in the text, after which we invite the reader to consult the glossary. Lastly, readers will find the bibliography and webliography of the main sources used for the text. The webliography primarily consists of websites, official blogs, YouTube videos, and Flickr, Facebook and Instagram pages, allowing the reader to explore the Chinese graffiti phenomenon independently.

All that remains, therefore, is to hope that you enjoy this book and that it takes you on a pleasant journey in spray paint.